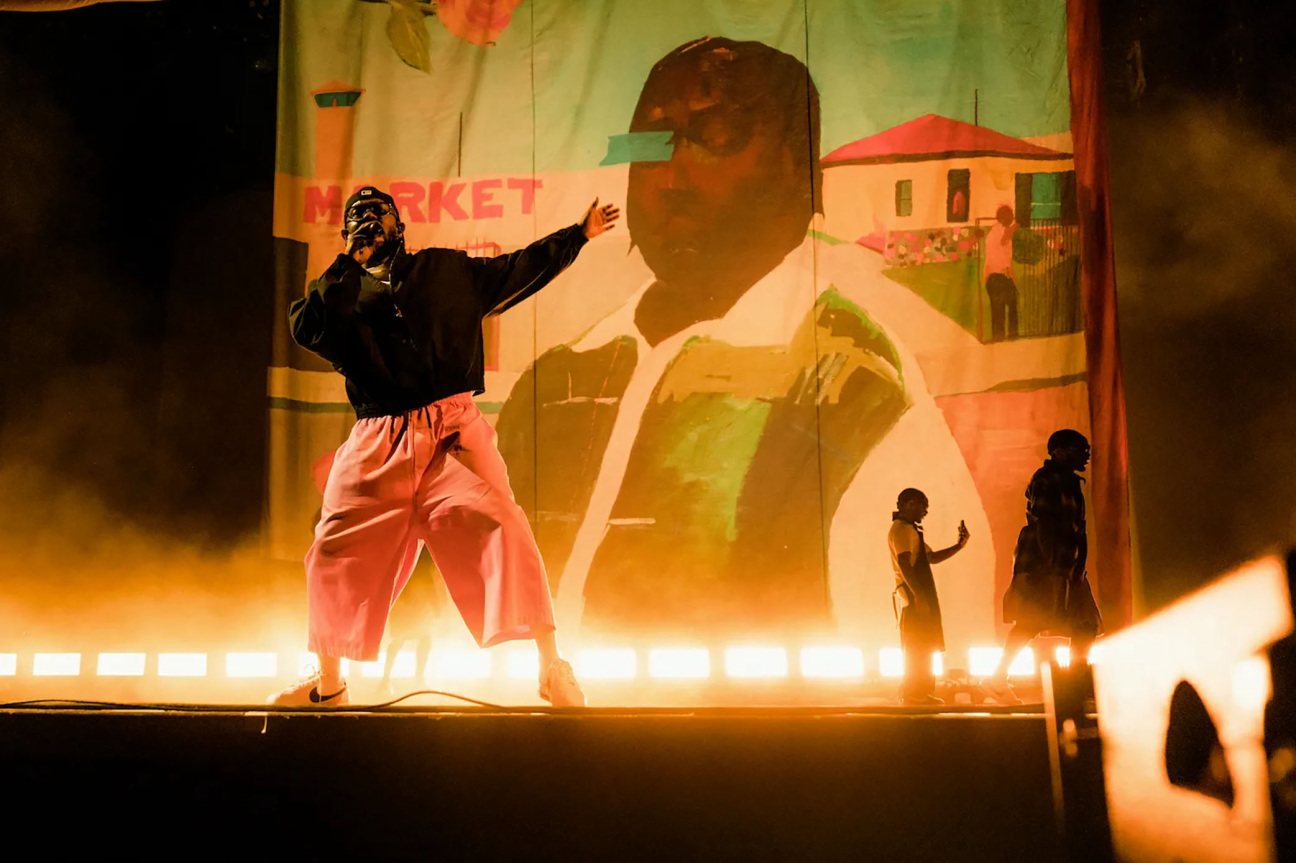

Taylor Swift isn’t the only Taylor who has been commanding attention on the concert stage lately. This summer, at the Chicago music festival Lollapalooza, monumental banners emblazoned with portraits by the Los Angeles-based artist Henry Taylor unfurled behind the rapper Kendrick Lamar. Taylor is one of a growing number of visual artists collaborating with musicians on ambitious live productions.

Of course, musicians and artists have a long history of teaming up—where would The Velvet Underground be without Andy Warhol’s iconic banana? But until now, their joint work has been more likely to appear in music videos and album covers than concert venues. That’s changing now that live events have come roaring back post-pandemic.

Concerts are big business again, and audiences expect an immersive experience. According to two surveys by the company QuestionPro, Taylor Swift’s Eras tour and Beyoncé’s Renaissance tour are on track to generate more than $10 billion combined, equivalent to the revenues of roughly two 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Artist-musician collaborations offer audiences something new, interdisciplinary, and unique to the live performance. They also showcase the mutual respect artists have for each other, bringing new fans to both. Rocker Liz Phair, for example, tapped the artist Natalie Frank to help produce the visuals for her upcoming tour celebrating the 30th anniversary of her cult album “Exile In Guyville,” 1993. The album was a song-by-song response to the Rolling Stones's “Exile on Main St.” and explored many of the same themes Frank does in her art: the female body, sexuality, pleasure, and the power of narrative.

“This show incorporates more fine art than I’ve ever seen in a rock show,” Frank says. “My work isn’t just a backdrop, it’s interactive, animated and interwoven with video that we’ve shot with actors. Some of the songs, like 'Flower,' solely use my visuals, drawings that have been orchestrated into moving Rorschachs. I have very strong synesthesia, so the combination of drawing, painting, and music comes naturally. Enlivening Liz’s strong feminist, punk narrative about sex, identity, and self determination has been a dream project.”

Visual artists are also core collaborators in performances held at The Sphere, an orb-shaped venue that opened in Las Vegas in September and houses 160,000 audio speakers and 600,000 square feet of LED panels. For U2’s concert series, which inaugurated the monumental space, the Irish music group and their creative directors, Es Devlin and Willie Williams, called upon artist Marco Brambilla to create a custom piece.

King Size, 2023, is a multisensory video of compiled media illustrating the many facets of Vegas, including Elvis, gambling, and generally over-the-top spectacle. In another part of U2’s set, screens projected work by the Irish artist John Gerrard: footage of flags made from gas flares and water vapor meant to express the existential threat of climate change.

Of course, many high-profile live performance collaborations predate the current wave. The Velvet Underground staged a series called the "Exploding Plastic Inevitable" in which the band played music surrounded by Warhol’s works. In 2000, artist Bill Viola made a three-song-long video triptych that went on tour with Nine Inch Nails, shifting from blue to orange to pink hues as ripples undulated through a body of water.

These collaborations produce visuals that are as distinct as the creators themselves. While Brambilla’s piece was a fantasia of high-tech, attention-addled digital media, Taylor’s work for Kendrick Lamar was intentionally analog. “We wanted a kind of show that didn’t depend on LED walls or anything like that—just backdrops revealing themselves over the course of the show in a lo-fi, theatrical, old-Broadway type of way,” Mike Carson, the show director and co-designer, told ARTnews. “If people at a festival see the same thing for eight hours in a day and then you come on at 11 p.m., how can you refresh the palate?”

in your life?

in your life?