“I want people to see me as a kind person,” says Jiab Prachakul, surrounded by the cabinet of curiosities that make up any artist’s studio. She has planted herself on a stool at the center of this organized chaos, wearing an all-white outfit and giving off the composed buoyancy of an elementary school teacher. It’s a rainy June day in Vannes, France—the compact port city where the Thai-born artist and her husband settled after the pandemic.

In the next hour, our dialogue will slalom between her preparations for “Rendezvous in Time,” her first New York solo show (up at Timothy Taylor until Oct. 14), and the more granular repercussions of being a self-taught Asian artist living in Europe whose art stardom (and mile-long waitlist) was born in a heartbeat.

For now, though, the 44-year-old is speaking about her two modes: the one she dubs as “leaping energy,” where she embraces any incoming interaction—to a fault, she admits—and its yang, which keeps her calm and grounded. The former gets to an essential quality in Prachakul’s painting as well as her personality: acting as a sponge for feeling. Pointing at a work in progress behind her, she wonders if she can make the table she’s outlining exude feeling. Can Prachakul inject it with the gust of aliveness she gives her human figures?

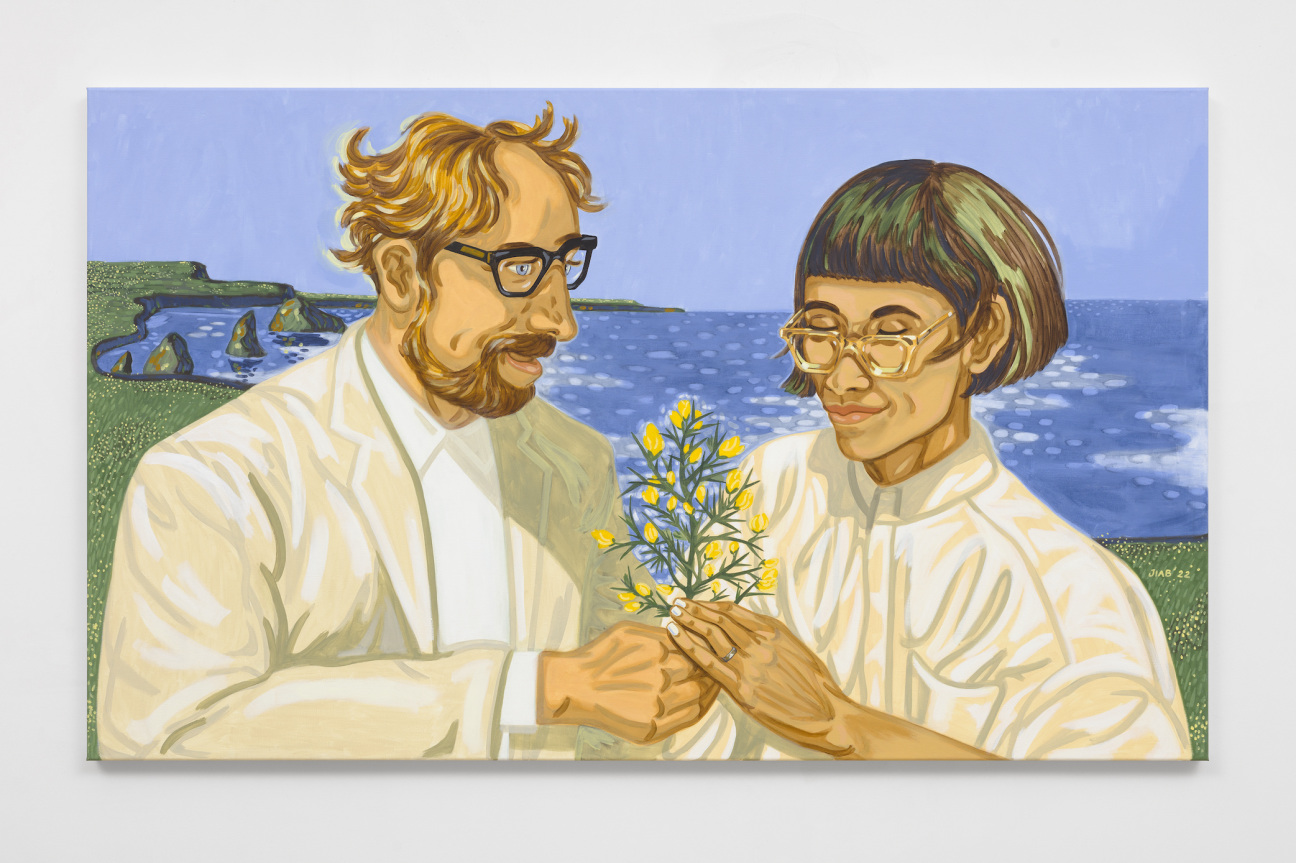

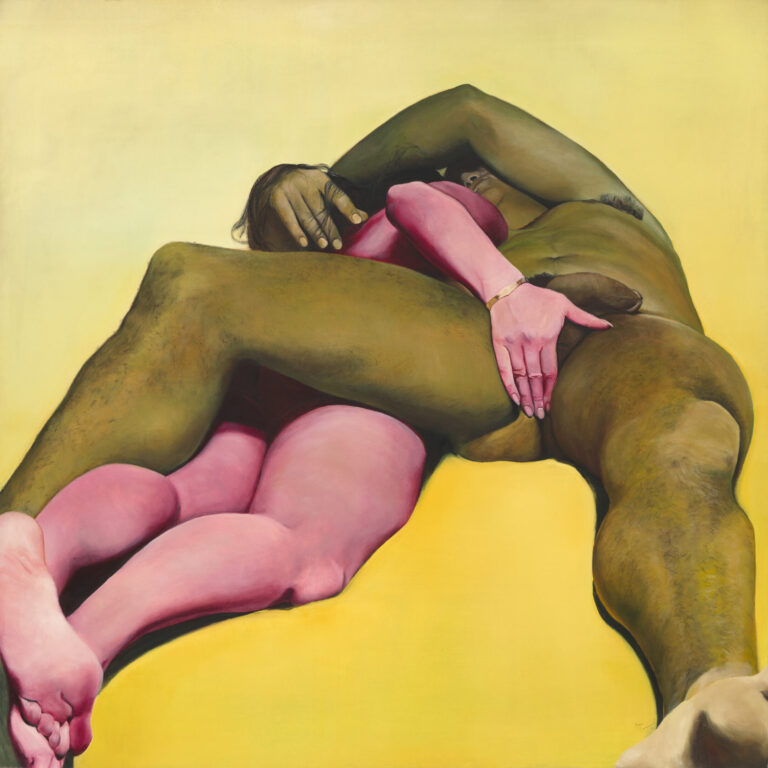

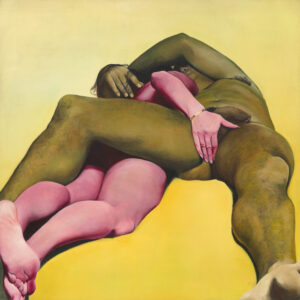

These sitters, who are mostly of the Asian diaspora and in her inner circle, are depicted in vignettes of everyday existence, suspended between breaths of reflection. It’s evident that the artist’s paintings listen, translating the architecture of an individual experience into a universal sentiment.

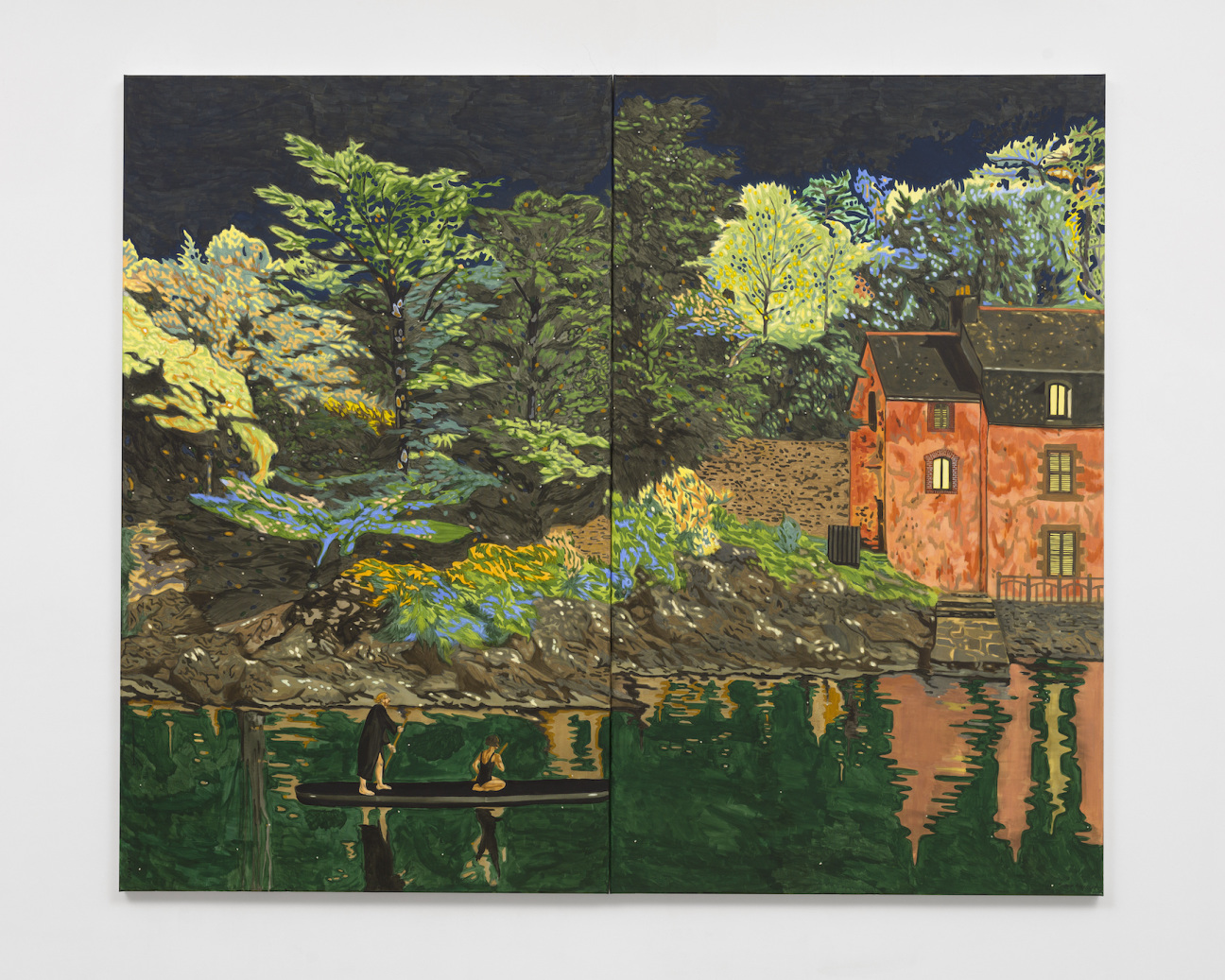

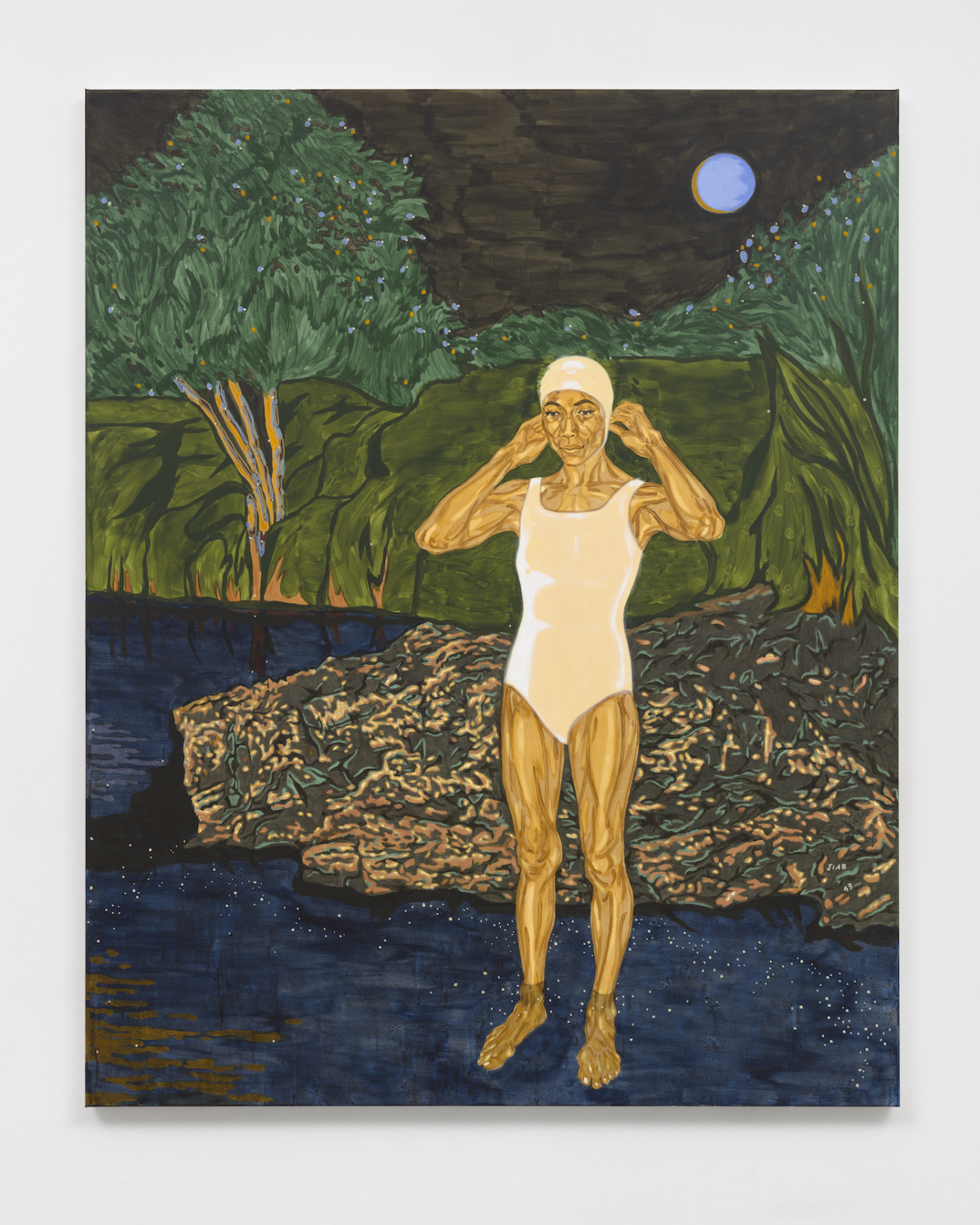

The nine canvases on view in “Rendezvous in Time” are postcards from the year 2022, juxtaposing the experience of settling into a life in Vannes and its surrounding slice of the reluctantly picturesque Breton coast with portraits of the people who’ve accompanied Prachakul through her past lives. Split between two rooms, representing night and day, these visual time stamps waft with precocious nostalgia and a deep sense of generosity. To mark the opening of the show last night, CULTURED time-traveled back to mid-June, when the conversation below took place.

CULTURED: What brought you to Vannes three years ago?

Jiab Prachakul: We were in Lyon, and I had really bad asthma. Previously I lived in London, Bangkok, and Berlin. [My husband] Guillaume said, “We should go to a place where you feel good, where we don't have to think about jobs.” We thought about Brittany, specifically Vannes, because the first time we came to France outside of Paris we came here. We spent 10 days [nearby] in Quiberon … At first, I was very scared of this part of the world.

CULTURED: What scared you?

Prachakul: I'm used to the Thai seaside. It's beautiful, the water is warm, people are really friendly, there's good food… The first time we came here we went to Port-Goulphar and Port-Coton in Belle-Île-en-Mer. I was so bloody scared. I kept looking at the sea foam that would spin and spin, and I was like, "Shit, if I fall, I'm going to die." Anyway, it turned out that Vannes is in a national park, and the air is really pure. So we moved here for that.

CULTURED: How has the change of pace influenced you?

Prachakul: Before we left Lyon, I told my husband that I wondered how the place was going to influence me. Berlin was so square and so hard—it made me feel like a boxer. That city is about survival. You have to fight during the winter. Then Lyon was really pleasant, but it's so bourgeois. And here, I feel so elevated, there’s such a different energy from the tides changing, the light…

When you live in different places, it’s like you have so many you’s inside of you. Sometimes one outgrows the other, and you have to manage. In Vannes, I feel really grounded. I do two hours of yoga a day. I stop working at 6 p.m. sharp, and then we go out to dip our feet in the water. We swim nearly all year round. It’s taught me to take time with my work. When I go back to London, I'm like, "Oh my God, how could I live like that?" It’s so rushed everywhere. In big cities, everything is at your fingertips. Here, we have one shop for everything.

CULTURED: How has living in Europe impacted what you choose to paint?

Prachakul: When you don't live in your country for a long time, you lose a sense of where you come from. I need to represent the Asian diaspora to remind myself that I exist. When I look at my friends or my family, I see how their life continues, and it builds the part of me that I never grew. It’s helped me merge into the identity I have in Europe.

When I think of a painting, I ask myself what can stand the test of time, what will keep mattering to me and to my sitter. For example, this painting behind me [points to a work in progress] is of Jeonga [Choi], my closest friend in Berlin. The painting shows a corner of her house I feel very attached to. I went through a divorce in Berlin, and for a year I would go back and forth between France and Berlin and stay at her place—and that corner became home for me, and for her, too. She has blond hair here, but maybe next year she won’t keep it. The painting is like a souvenir for both of us; together we understand what is happening in our lives.

CULTURED: It's like a meeting place in a way, a venn diagram of your experiences. What kind of conversations are you having with your sitters?

Prachakul: Usually, before I start a painting with a new sitter, I send them a set of questions. I ask them to tell me their first memory as a child, their best achievements, how they see themselves in the world, how they protect themselves, how they feel other people look at them… They’re questions I ask myself, too. I paint a lot of people over and over, like my friend Jeonga, so over time I’ll expand the questions.

Jeonga had a baby four years ago, and it was really tough. She’s a super cool mom—she doesn’t want to become a mom mom. I asked her what the pros and cons of being a mom are, and she said the pro is to have one creature that loves you unconditionally and that the con is that she has to reflect herself to her kid all the time. That is so difficult for me with my family, too. When they come to visit, we have a bit of a culture clash because I don’t have the same habits as Thai people anymore. So I have to reflect myself through them and try to link back to the self that is in them, like finding a bridge.

CULTURED: Do you ever feel stuck when you’re painting?

Prachakul: Of course. My husband helps me; he’s so encouraging. Yoga helps a lot, too. Whatever I feel, I just go steadily. The work is about the process of time, not about someone saying “you are so talented.” It’s about being there. When you feel bad you can just paint one detail, or do the lines. That’s still moving forward. Because I'm quite old—I'm 44—and I've been working independently for so long, I'm really structured.

CULTURED: You’ve had ever-increasing exposure in the past few years. There are long wait lists for your work, and you’re opening an anticipated solo show in September. How do you resist being swallowed by the market’s pressures?

Prachakul: I’ve been working really hard for a long time. I appreciate the outcome. But when I reach success like this, it’s like, “I did this work before. The only thing that matters is doing the work.” It’s so nice to be in high demand, but it’s really about the work you want to do.

CULTURED: Has it changed how you see yourself?

Prachakul: A little bit. I don't want to be very known. Of course I want exposure, and I want to talk about my work. But I don't want to be recognized in public. In Lyon, it started a bit after I won the [BP Portrait Award], and it made me so nervous. Things come and go, though, and what really matters is what I’m doing next.

CULTURED: What are you most excited about in the future? Anything you’re experimenting with right now?

Prachakul: With this Timothy Taylor show, I tried a lot of new things. I had a two-person show in London with Patty Chang in 2022. I saw my paintings in the gallery, and they felt like Instagram shots. And I was like, “So what?” The work sold, people wanted it, but when I looked at it I knew I wanted to do something more. With “Rendezvous in Time,” we’re separating the gallery into two rooms: a night room and a day room. I want to tear the viewer out of the world they know.

And then there’s a painting [in the show] that will be accompanied by a sound work. It’s just ambient sounds that I hear every day—birds, the French radio, those kinds of little things. I wanted to add something for the people who see the work in person; I want to offer them an experience that’s more than what they see on Instagram.

I also started a sculpture. It’s a new project that Micki Meng and Chloe Waddington want to support. They asked me if I wanted to make sculptures, and I told them, “I have asthma, I don’t want to work with clay.” But they’re helping me make sculptures without clay, by doing 3D scans of my sitters. I'm a little nervous to see how I can translate the language from my paintings into other mediums. Then eventually I want to do a short film about the lives of my sitters.

CULTURED: What would you say your work is for, and what is it against?

Prachakul: It’s for feeling and intimate moments where you feel meditative. It’s for nostalgia that’s been thought out, cleaned, and reconstructed. It’s about accepting who you are as a person. I never make work that feels aggressive. If I’m angry, I digest that feeling carefully and for a long time, and I don’t let it enter my work. I don’t want to transfer the shit I feel to my audience.

in your life?

in your life?