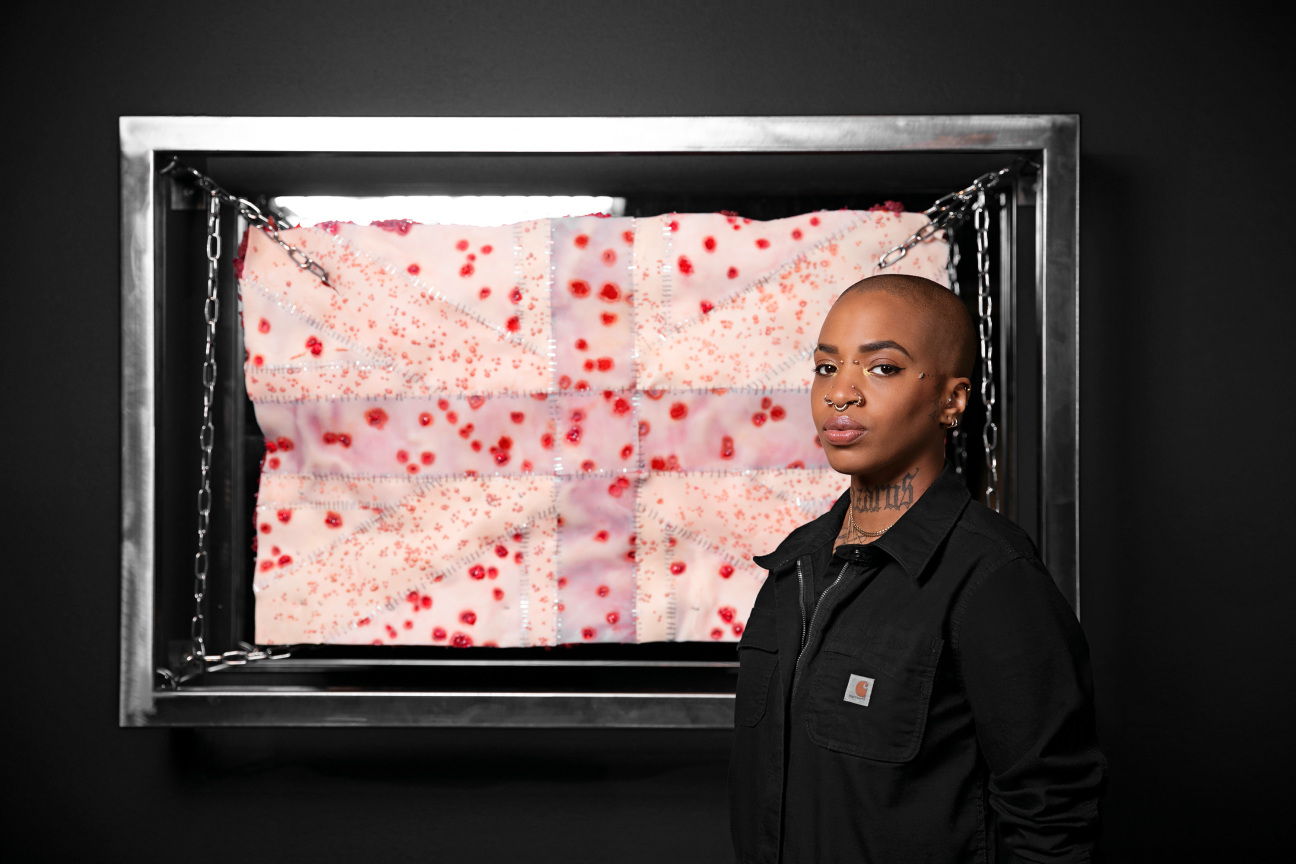

Doreen Lynette Garner, who uses the moniker King Cobra, wants you to say the titles of her work out loud. In her new show at JTT, there are three pieces in particular that she would like you to enunciate. Lined up on a white wall, like shooting targets, three casts of white asses, in all their pimply and hairy glory, sit waiting for you to name them. You’ll probably see your reflection, since the asses are placed in front of large mirrors. This exchange is at the center of “White Meat,” which opens today in New York. Through silicone sculptures that marry minimalism with excessive, even grotesque, detail, the show asks viewers to confront the abjection implicit in whiteness. Cobra called up CULTURED to talk about stealing dirt from J. Marion Sims’s grave, bringing mayonnaise into a gallery space, and making a white dread rat king.

CULTURED: In the past few years, you’ve focused on whiteness and white flesh, specifically diseased white flesh. What keeps you working with this subject matter?

King Cobra: The work that I had been doing, which focused mostly on the exploitation of Black bodies through the medical industry, had always required me to show dismembered body parts. And constantly seeing those images was starting to settle a bit weird with me. When I started working with white flesh, it felt a lot easier. I didn’t have a connection to it in the same way that I did when I would make silicone body parts that had brown pigment in them. It allowed me to think of my work in a way that wasn't so attached to my own appearance, and I was actually able to be a little bit more grotesque with my creative process.

CULTURED: How does that translate into your sculptures?

Cobra: I've been working with imagery of diseases that were brought over during colonization, like the bubonic plague, smallpox, scarlet fever, and syphilis. A lot of those diseases cause blemishes on the skin. As I was creating white flesh, I would pack in different tones of felting powder. It moved from a strictly casting process to more of an encaustic painting, working with the different layers of silicone as it sets up. There is a lot more opportunity for me to get creative with how I would depict diseases on semi-translucent skin.

CULTURED: Diseases have stages, and the sculptures you’re making are frozen in time, showing only one of them. How are you thinking about temporality with these?

Cobra: I think that’s most apparent with the “Cracker” series I’ve been working on. There are some where there’s barely any sores, and some are covered and almost falling apart. I probably made about 150 crackers, and I selected nine crackers [for the show]. The tones and the sores are based on portraits of the first nine presidents of the United States, using colors from their faces, what they’re wearing, or the backgrounds of paintings.

CULTURED: Your previous work and exhibitions have often drawn on specific historical events or figures, like the 1773 uprising on the slave ship New Britannia, or J. Marion Sims and his torturous experiments on Black women. For “White Meat,” are you probing different historical events?

Cobra: It’s a lot of the same history, particularly with When You Are Between The Devil And The Deep Blue Sea, 2022, which references slave captains letting sharks trail behind the ship in order to make enslaved abductees afraid to jump over and commit suicide. That’s a theme that was also expressed in “Revolted” at the New Museum. With J. Marion Sims, I’m pushing him lightly towards the background, but he’s definitely still being engaged. In this show, I casted a rendering of his head in silicone that’s colored like baloney. I went to his grave in Greenwood Cemetery and stole some dirt and mixed it into the silicone.

CULTURED: Besides these historical references, what have you been surrounding yourself with while working?

Cobra: I’ve been casually reading a few Octavia E. Butler books in my travels back and forth to the studio. I’ve been watching a lot of stand-up, like Nick Kroll, Sebastian Maniscalco, and Bill Burr. And Succession … I feel like in those scenarios you get to understand whiteness as a performance, and that was something I wanted to get into—thinking about people's faces and how they age, or how they uncomfortably laugh. These are just the things that I've observed about white people in my everyday life. As a Black woman with autism, I feel like I'm pretty critical of people's behaviors. I’ve also been watching a few panel discussions, including “Does Abstraction Belong to White People,” about what it means to have complicated or loaded materials that make a really simple object, like me mixing grave dirt to make a big sheet of baloney, which is basically a pink circle.

CULTURED: In another sneak peek from “White Meat,” I saw you were taking on white dreadlocks and assholes.

Cobra: A lot of people feel the same about white dreadlocks, which is that you want to cut them off the person that is wearing them. And I thought that it was interesting to use these scalps as a means to create a “tribal necklace.” It's like, Who is the necklace for? Who collected these scalps? And how do we regard the term ‘tribal’ today amongst so much cultural dilution? Also just thinking about the lengths some white people go to to look less white is mind-boggling. With that piece, I wanted everyone to be collectively disgusted with seeing them all en masse. It kind of starts to resemble a rat king.

CULTURED: A few years ago in a video for Art21, you said you “want the audience to walk away feeling like they can’t unsee what they just saw.” What’s your relationship to realism, surrealism, and hyperrealism?

Cobra: I'm more interested in the uncanny, which is in between all of those. It's that kind of gut feeling where something is just not right and you continue thinking about it after you leave the space. I try to place things we interact with on a daily basis in my work, to get you to remember the things you saw in the gallery. The consistent theme within this show is mayonnaise, splooged over frames and in cream pies…

CULTURED: What do you want “White Meat” to trigger and for whom?

Cobra: I just want there to be an acknowledgement that whiteness finds itself often in the world of abjection, as far as how people create images and objects. I think because I'm a Black person with a vagina creating these works, it feels a lot different. It’s more of a visual criticism of whiteness. I’ve been getting a lot of trolls online, and it often seems like people are getting most upset that I’m simply acknowledging whiteness and history. It’s almost as if they do not want their whiteness to be perceived. I’m looking forward to other Black people seeing the show and having a good time—laughing at some of the pieces and even having a chance to be critical about the work without having to experience an abundance of Black body parts rendered through mutilation.

"White Meat" is on view through May 13, 2023 at JTT in New York.

in your life?

in your life?