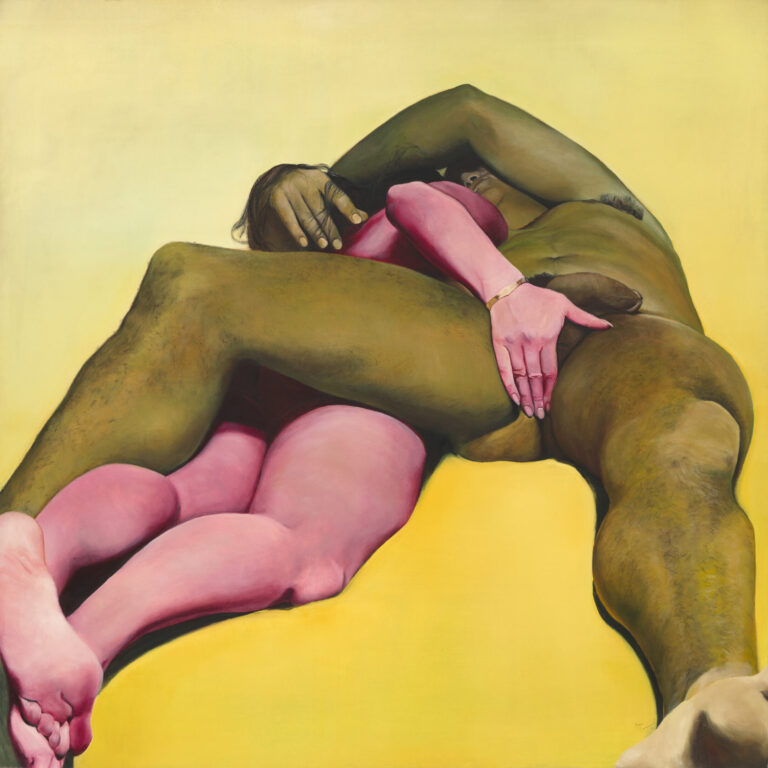

Penny Slinger and Polly Borland did not become artists to be likable. The duo have had long, polymorphous, and disruptive careers. London-born Slinger, 76, uses the erotic and divine as lenses through which to apprehend and dissect femininity. Melbourne-raised Borland, 64, investigates celebrity, abjection, ego, and authenticity through her genre-bending photographic practice. Over the past few years, the two have come together to play with the aging female form and its possibilities. The fruit of their rich collaboration, “Playpen,” is on display at Lyles & King in New York starting today. CULTURED took this opportunity to chat with Slinger and Borland about using the camera as a mirror, exploring fluidity beyond gender, and rescuing older women from invisibility.

CULTURED: What instincts came up in the collaborative process of making this show?

Penny Slinger: It was an alchemical journey that we went on together, stimulated by Polly coming to me and saying that she felt kind of stuck and wanted to collaborate.

Polly Borland: I hadn't lived in Australia for over 30 years, and I somehow got stuck there for a year and a half when the pandemic hit. I had a show opening at Nino Mier, my gallery in LA, and they were all selfies of me. It was the first time I had revealed myself in that way in my work, and I wasn't there for the opening. I had no real birthing moment with the work, and I felt lost. Penny and I had done a talk a few years before on “reframing the muse.” So, when I came back to LA, I emailed her.

I put myself in the role of the muse, and it was a journey of transformation. We used each session as a playground where Penny would oversee the play but got to play as well. It was a very safe environment for me to be free, and in a body that was 20 pounds heavier because of Covid. There were a lot of things that normally I would have been extremely self-conscious about … For me, the camera is a tool of control, and to relinquish that control to another person, albeit an artist and someone that is in sympathy with me, was a big step.

Slinger: It's super important at this point in time, especially for women, to collaborate. We've been put in this competition aspect with each other. Now, I think we've got to leave all that behind and come to a next level of interaction where we're really helping and supporting each other. I built my practice for many years, starting with photographing myself but extending that to other people, having that camera be like a mirror and the person behind the camera being invisible. You're entering into this symbiotic situation where you're reflections of each other and it's all one energy.

What we did in this work together is something that I really stand behind, which is saying: a muse is someone who can inspire and embody boundless creativity. In each section, we reinvented the idea of the body. It's like a study of morphology, but each particular facet is opening up the body to look at it in another way, culminating in our doing the exquisite corpse, where we're chopping the body in three and bringing together all kinds of different combinations. It's really celebrating self-invention.

Borland: Each session enabled me to go into an almost semi-conscious state. It was like a psychodrama play where I was able to express myself physically in a way that I'd probably never really been able to. It was the act of being seen by Penny, but also engaging in the materials. What did the fabric mean? What did the clay mean? What did the sensory experience mean? It wasn’t an intellectual thought process; it just unfolded as I became more in touch with my body. Like the fruit within the stockings—it was sort of fleshy, wet, and quite hard. It wasn’t comfortable. Each material brought out different poses and sensual experiences.

Slinger: All we had to rely on was our creativity and our ability to respond to the materials and to everything we bought into that playpen, and let it come through like children—playing, fresh, and inquisitive, and not caring what anyone else thought about it.

CULTURED: The images in “Playpen” play with the grotesque in beauty, or beauty in the grotesque, which can be seen as a commentary on the expectations projected onto women’s bodies, but also on the freedom that’s found in bodily modification. Could you speak to that tension?

Slinger: At this moment, when we've got much more of an opening to gender fluidity, we're certainly exploring that in the images we have. But we're also exploring a fluidity that goes beyond just definitions of gender, one that merges with elements and creatures and expands the idea of what is beautiful or ugly into a much wider palette … Like with Polly putting these fruits in different parts of her body, it becomes an altered kind of being. We didn't have to go to the plastic surgeon for this, we just had to use what was in our refrigerator and our costume cupboard.

Borland: It's all non-binary, actually, because it's not about the opposites, it's about creating something new … I've become increasingly interested in viewing things through paradigms that I wouldn't normally look through, and I think that's really where I'm at with that. The inside’s coming out, the outside’s going in, and it's all mixed together in this cacophony.

Slinger: It's like the edge where the water meets the land, and you've got all kinds of new, interesting creatures forming. We're in that place of forming creatures together.

CULTURED: There’s something in this work that really evokes hunger, or a sort of unleashed desire. What are you two hungry for right now?

Slinger: I'm hungry for the recognition of the female elder! When I was younger, I made my book 50% The Visible Woman to show that we're only seeing half of a person when we're looking at her surface. Now, it’s like how does one make a woman of a certain age visible? I think it’s important for society that we allow the wisdom of experience to percolate back in, and that accumulated beauty is not seen as a faded rose but allowed to bloom.

Borland: Since doing this project with Penny, I feel so reenergized in my practice. It's interesting that, at the age of 64, I have the kind of drive and creativity of when I was in my early 20s. I’m just raring to go.

"Playpen" is on view through May 13, 2023 at Lyles & King in New York.

in your life?

in your life?