“Writing a memoir is reliving a lot — reliving, reassessing, and re-evaluating different moments in my development,” says Moshe Safdie. Reflection is top of mind for the 84-year-old Israeli-Canadian-American architect, who spent his COVID-19 lockdown penning his book released today, If Walls Could Speak: My Life in Architecture, which reads like a memoir-cum-travel diary-cum-manifesto for responsible, thoughtful design.

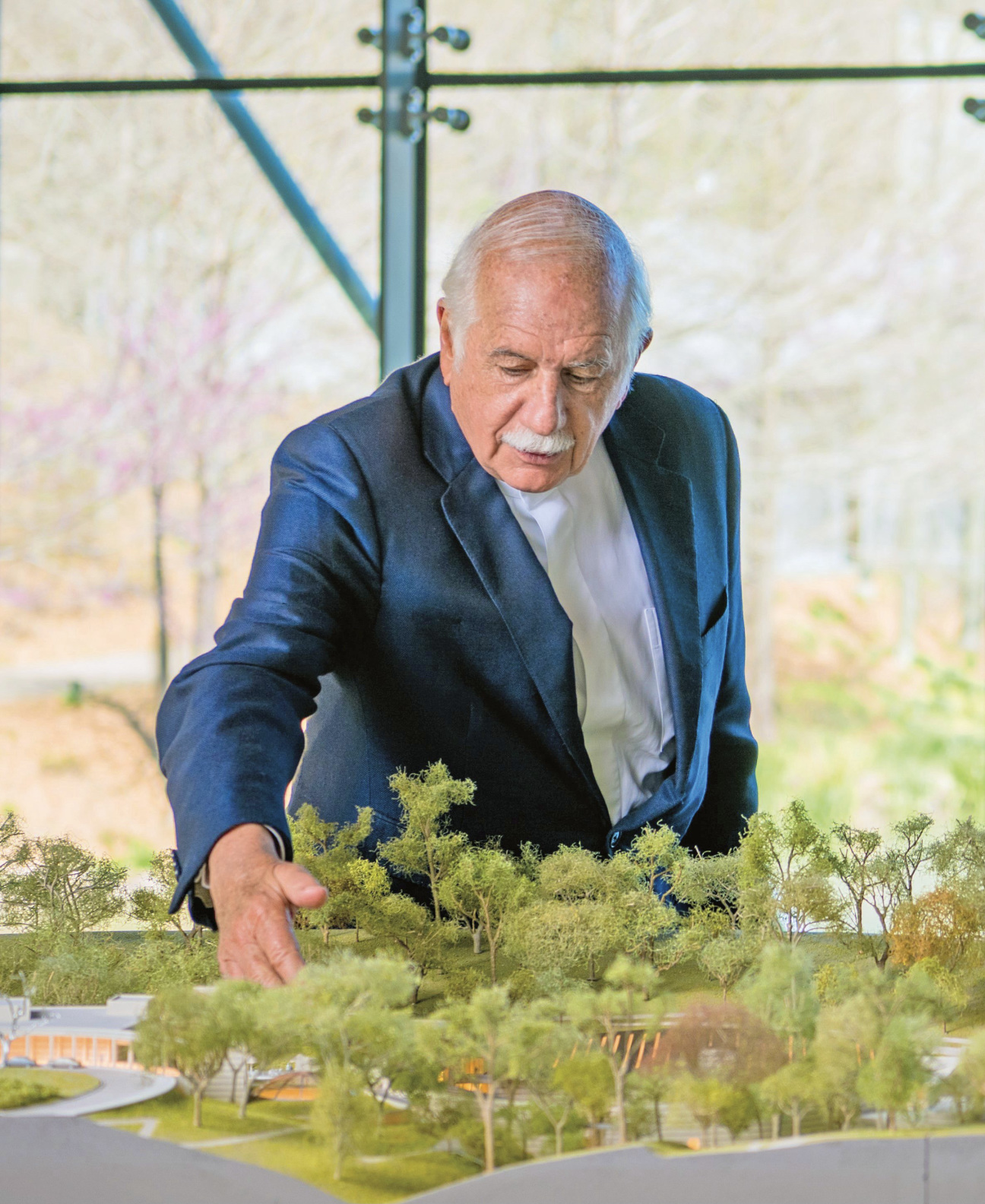

The architect has been designing innovative, sustainability-focused, socially-forward projects for five decades and counting, starting with his McGill University Faculty of Engineering thesis, Habitat ’67, an exploration of the future of factory-built housing that—still to its architect’s quiet disbelief—was constructed in Montreal as the Canadian Pavilion for the Expo 67. Since then, the former apprentice of Louis Kahn, former director of the Urban Design Program at Harvard University Graduate School of Design, and lifelong professor has gone on to design buildings such as the National Gallery of Canada, the Yad Vashem Holocaust History Museum in Israel, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, and Jewel Changi Airport in Singapore. What connects them all, however, is not a specific style, a use of glass or geometries, or a material lust: each Safdie Architects project was designed to the benefit of its users and their environment.

Safdie is a starchitect in all definitions of the word, and yet in all its connotations, he is not. He eschews the draw of contemporary practitioners’ penchant for “sculptural self-expression” afforded by new digital design technologies—ones that, like nearly all global design studios, he employs in his office, as well—and maintains that “the environment that produces this kind of icon, never-before-seen, everything-is-a-new-invention design is very counter-Darwinian.” Instead of focusing on statement-making, he feels that architecture should “be evolving and incrementally improving” upon itself with each project. With newly invigorated, mainstream industry conversations around environmental design, Safdie is hopeful “we’re cycling out” of the desire to declare oneself in structure.

It’s humility that sets Safdie apart in his demeanor and his approach to architecture. He credits this to lessons learned in Jerusalem, where the architect has worked for many years of his life, along with Canada, Singapore, and Boston, where he currently lives, headquarters his studio, and teaches at the GSD.

“It taught me that one has to be extremely attentive to culture—to a tradition of a place. It’s actually a kind of particular humility. You accept it as worthy,” he explains of Israel’s capital, a holy city for followers of the three Abrahamic faiths and a place with a truly ancient history. “I think some of my peers came into the historic city and just did their own thing. Total contradiction is a kind of arrogance. Jerusalem healed me from that.” Safdie was born in Haifa, British Mandate of Palestine, and lived on a kibbutz before moving to Montreal in 1953 at age 15. To “soften the blow” of leaving the only home he ever knew, his mother whisked him and his siblings away to Rome, London, and Paris before planting them firmly in Canada where his father had already begun rebuilding their lives. These travels were a sort of Grand Tour for the young boy, and an introduction to the world of design and culture where diversity is a large part of the appeal. His curiosity for geography has guided his work since.

“You can make contemporary buildings that still feel they belong and rooted in place, which is always more satisfying,” the architect explains of how he designs in any context. Having come up in architecture at the same time as the Postmodernist greats like Philip Johnson and Frank Gehry, he considers his work a “counterpoint” to these -ism designers, though maintains that, despite it, Gehry is a close friend. (Johnson, as revealed in the new book, stopped sending invitations after Safdie wrote a scathing critique of his 1984 AT&T Building in New York.)

In person, Safdie is warm and intentional in conversation. He is excited by discussions that question the design world’s status quo. After all, it’s a core tenet of his profession, he believes, to strive to constantly innovate the processes and systems in which one works. “Louis Kahn used to ask, ‘What does a building want to be?’ and my reading into that is a building wants to be what it’s constructed for,” he says. Habitat ’67 was an idealist exercise in what form a middle-class housing complex, constructed with prefabricated modules and allowing “a garden for everyone,” could take. Ultimately, the construction technology did not match up with his design—and still does not—for a modular system that could be contextually replicable on the kind of mass scale Safdie had hoped. It’s a lesson every architect has learned at one point in their career. Its principles of efficiency and livability, however, are foundational to the current “green” movement in design, where new technologies are helping build systems that are sustainable and environmentally friendly. Safdie too is invested in this future, particularly with the idea that adding program-motivated gardens to projects creates environments that people just want to be in, as inspired by his work in Singapore. Mixed-use projects are at the forefront of his thoughts, as well, for the utility they can bring in scaling down a mega-city. Currently, Epic Games is digitizing Habitat ’67, so that gamers can interact with it virtually around the world. Safdie is hopeful that one day he’ll have the opportunity to build a mixed-use version of the project in real life.

As long as his health allows, the architect maintains that he has no plans to slow down, although he is grateful for the time he was given to look back on his work and to write the stories he’d been wanting to tell. “The best way to evaluate a work of architecture is to visit it 25 years later,” he says. In Safdie’s philosophy, a project is technically successful when it achieves its programmatic needs; architecture happens when it this is accompanied by a design that is both attractive, constructed for longevity, and creates a sense of well-being for its occupants, current and future. Designing for the latter, however, is often something that still baffles him. “It’s a mystery,” he laughs. “I mean, I know when that happens, but I certainly couldn’t write a prescription.”

in your life?

in your life?