David Hockney wipes his thumb on his pants, attempting to rid his fingers of paint—a regular habit for painters whose clothes often end up Jackson Pollock derivatives. Hockney was acting out of habit not circumstance, ironically, as his fingers were devoid of the iconic bright oils he’d popularized since the 1960s. In fact, his hands hadn’t touched paint all day; he’d been using his new favorite medium: the iPad.

It is 2011, and Hockney is preparing for his third iPad exhibition that year. The art world and public are perplexed. On a small Canadian radio show, the disc jockey is confounded and pushes Hockney to delegate the iPad as a “lesser” artistic medium, but the artist doesn’t bite. “It's just a very new tool that's quiet. [It] will open up a lot of things. I mean, that's all. I'm still exploring. I haven't finished,” Hockney coos with a hint of British cheek. The DJ is left baffled and Hockney leaves to presumably smoke a cigarette. Three months later, Hockney submits a The New Yorker cover created with Apple’s tablet—the drawing got its own article: “He Draw on iPad.”

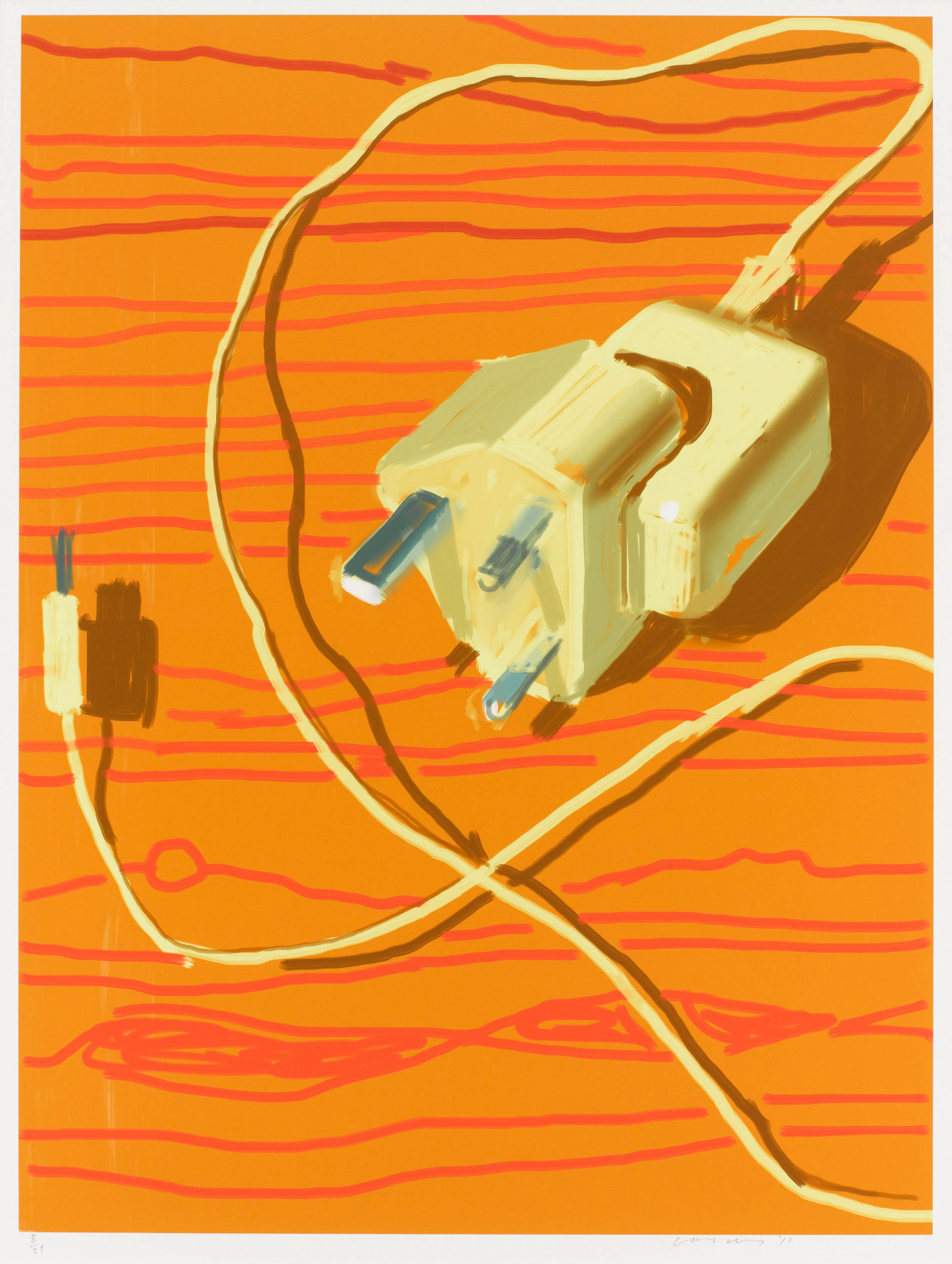

More than a decade later, Hockney’s affection for digital art is now comically common and boosted by technological improvements. Whereas Hockney struggled in the ’80s to make computer technology popular, the icons of today seem quite comfortable with digital alternatives. Venice Biennale favorite Christina Quarles transfers broad paint strokes to her iPad before moving back to canvas; David Zwirner star Andra Ursuța takes to digital programs to “remove the human hand,” and Los Angeles ultra-contemporary darling Canyon Castator uses an iPad almost exclusively to draw. And yet, a stigma around the medium persists. “I think it’s weird that so many painters either choose to or pretend to live in a state of technological denialism to preserve the market fetishized puritanical obsession of oil on canvas,” Castator says. “It’s much more interesting to me how painters use new tools and technologies to expand on and reinvigorate the possibilities within the medium.”

Despite initial trepidation, a few forward thinkers are pursuing these opportunities and diluting the porous boundaries between reality and technology. Whether it's using app-based technology such as Procreate or harnessing the computing power of metadata, artists and their curatorial champions are finding themselves facing unhindered frontiers. Marina Abramović, Anish Kapoor and Alex Israel, for instance, have all dipped their toes into augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR). They were followed by Precious Okoyomon and KAWS at Serpentine Gallery, while AcuteArt took Jeff Koons, Olafur Eliasson, Cao Fei and Ai Weiwei into the AR/VR universe. So far, it’s been a hit—both critically, commercially and philosophically. “I think it's interesting to think about this radical paradigm shift when a new medium not only introduces possibilities for what the audience can be and how you reach people but [can instigate] debate on policy around artwork,” muses Daniel Birnbaum, the former curator and director of the Venice Biennale and Director of AcuteArt. “What can art be? And I actually do think that these new mediums are doing that.”

“With AR and VR we’ve reached bigger audiences than anything else I’ve been involved with,” he continues. “Once or twice in every century, there is a new visual medium that appears that upheaves the art market. More people saw the AR work than they did the Venice Biennale.” While art has been prohibited geographically, artists are seeing technology as an opportunity to break down barriers and enter new audiences. “Nina Chanel Abney wanted us to place her work in Washington during a Black Lives Matter March, we had a possibility of interventions in the public sphere. It's a little bit like graffiti or a little bit like situationist works from the 1960s where you can create juxtapositions with monuments in the city itself,” Birnbaum explains, “We are working in millimeters of placement at this point.” He paints the picture of one of Abney’s infamous Black figurative works hovering above the White House, though he admits doesn’t know the exact legality of it. Still, the possibilities do make one vibrate.

Is AR/VR the next iteration of art? Is the iPad the next sketchbook? It may make for an interesting new frontier of art; one where 85 percent of Americans with smartphones feel included.

in your life?

in your life?