Inside the sterile suburbs where I was raised, as a young African American boy, I witnessed firsthand the power of Kanye West. Blasting “All Falls Down” on the way to middle-school carpool drop-offs and corporate jobs, with one hand on the wheel and the other applying makeup, elegant mothers slipped out of their mundane roles and suburban personas. Jutting their necks, rapping fiercely, these women drifted into lucid dreams. Stern fathers joined them. When “I’ll Fly Away” wafted through living room speakers, hips swayed; anger evaporated; stiff backs loosened. “Slow Jamz”eased pain. “The New Workout Plan” initiated laughter. As the songs changed, time slowed. Back then, these women and men raised their hands high and closed their eyes in solemn meditation, in soul-deep communion. Something like freedom coated their auras.

For nearly two decades, West’s legacy has been one of mythic proportions. Thousands cling to his every word and emulate his ideas. Millions are said to walk in his shoes and clothes. The cultural impact of his art is irrefutable.

Born in Atlanta and raised in Chicago, West first received attention as a producer, working with artists such as Jay-Z, Alicia Keys and Ludacris. In 2004, he released his first solo album, The College Dropout, a soulful love letter to individuality and a questioning of societal assertions. Each of his ensuing albums traces his own personal journey and development as a musician. The through line from Late Registration’s inclusion of orchestral strings, to Graduation’s turn toward pop music to 808s & Heartbreak’s electropop, which seta new standard for what hip-hop could be, is West’s mastery of an impressively wide range of styles. Those albums and the subsequent My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, Yeezus, The Life of Pablo, 2018’s Ye and last fall’s Jesus is King cemented his status among the most critically acclaimed artists of the 21st century, earning him 69 Grammy nominations and 21 wins. For swarms of fans, his music has long been considered gospel, inspiring confidence and consciousness and defining an era.

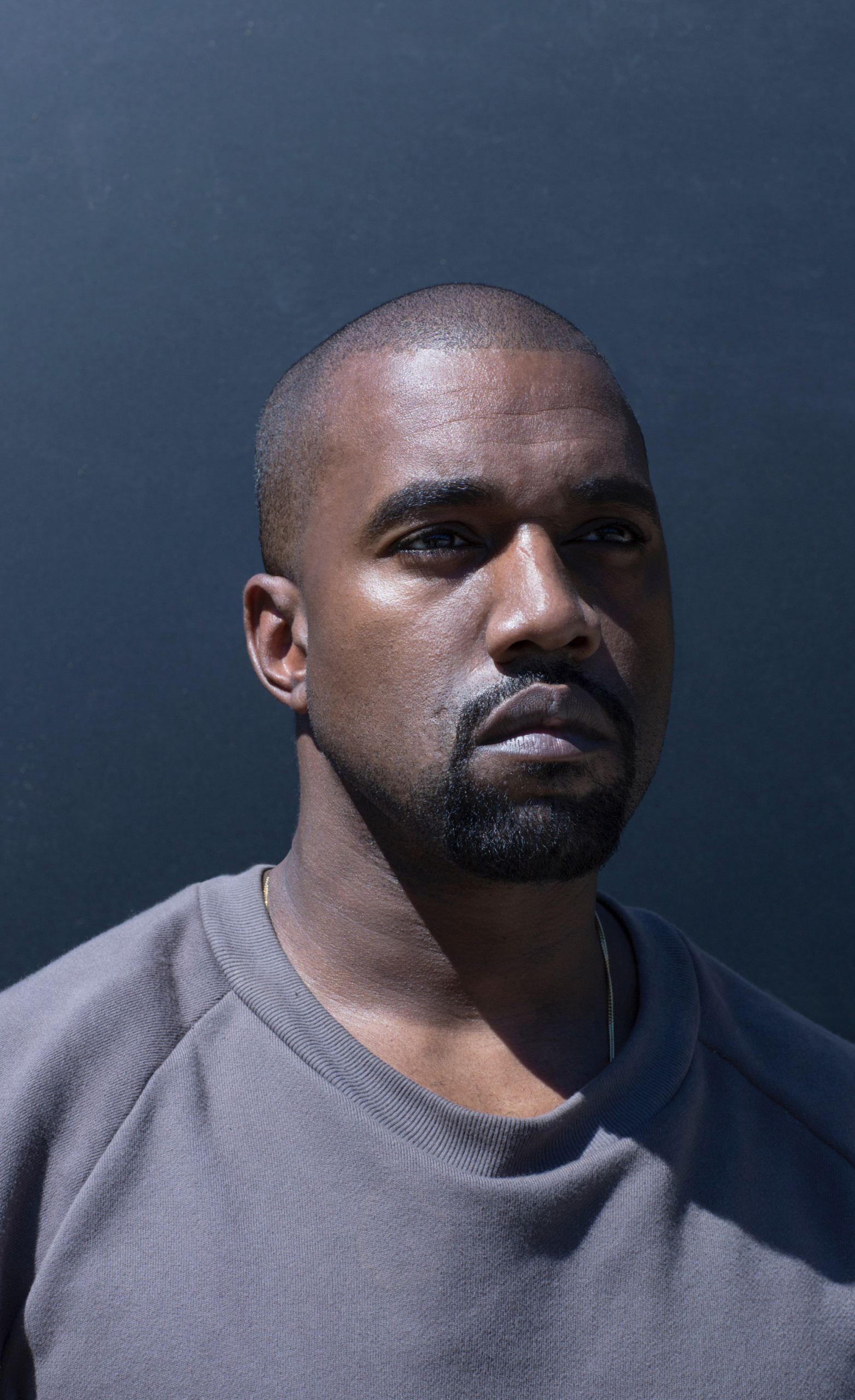

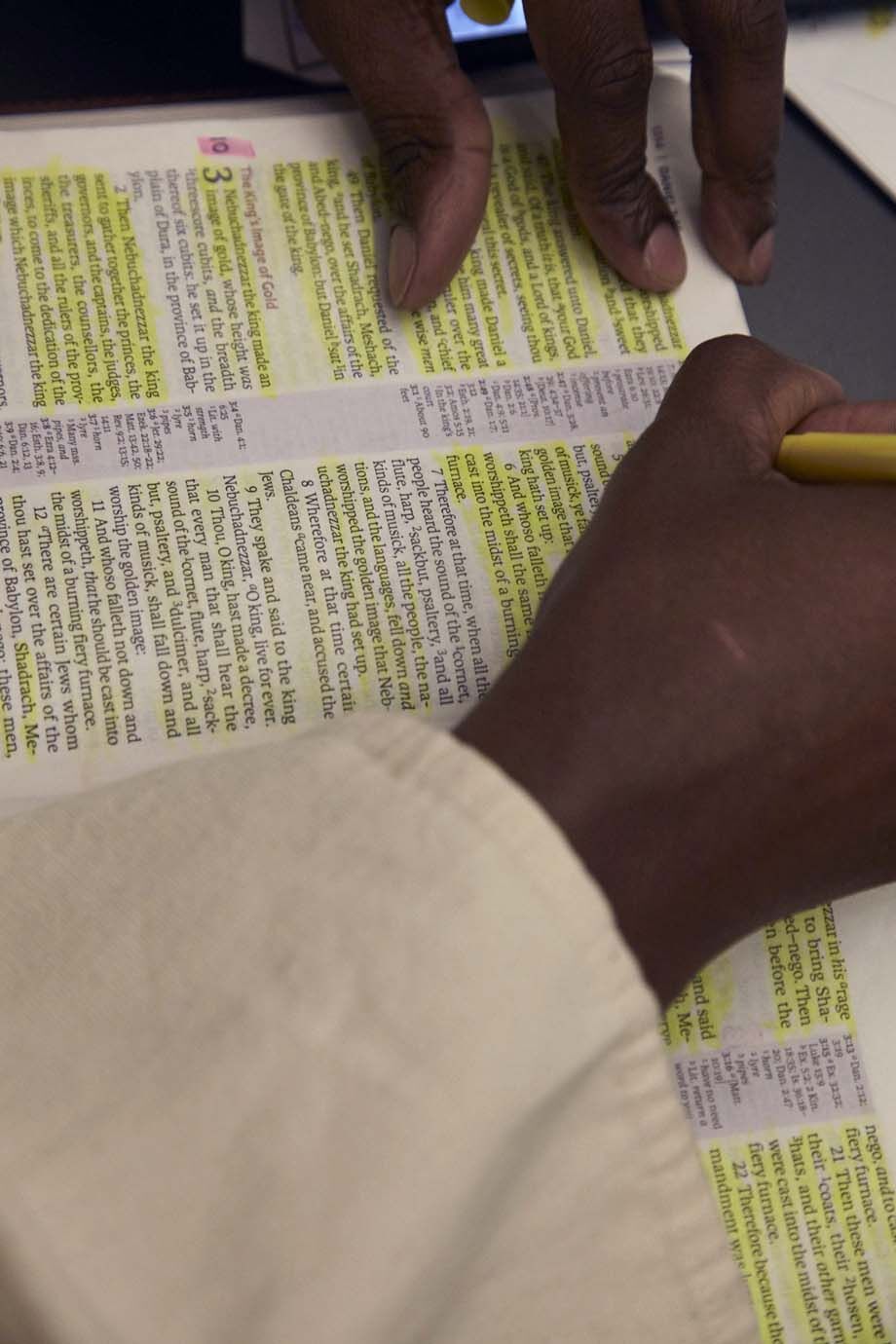

“The job of a visionary is to explain the vision, to write it down,to make it clear,” West tells me hours before the debut of his opera at the Hollywood Bowl. Tucked inside a private room, sprawled on a couch with a copy of the King James Bible, he’s a portrait of piquant insouciance. Dressed in slouchy parachute pants, a seamless sweatshirt, brown cubist vest and matching boots, West looks well-rested. Though he has a habit of changing rhythm frequently, he’s easy to understand. “Sometimes you get frustrated that people can’t see the vision, but they can’t see it unless you make it clear,” he says. “The difficult thing before was that people couldn’t see it until it was created. I had to explain to people; I had to try and get financing. Now that God has blessed us so much with the success of Yeezy, I can just go and independently produce an opera on Nebuchadnezzar.”

It is West’s commercial success in fashion that funds his new artistic endeavor. After an initial collaboration with Nike, he announced his Yeezy Boosts sneaker partnership with Adidas in 2013.He officially launched Yeezy Season 1, a stripped-down, ready-to-wear shoe and apparel collection with Adidas in 2015. The first limited-edition release of the Yeezy Boost 750 sold out within 10 minutes, a phenomenon that has continued over the last five years with successive global releases of the highly-covetable sneakers, considered one of the most influential brands in the world. Last summer,Forbes estimated the brand would top 1.5 billion dollars in annual sales in 2019.

When I mention West’s historic achievements within the socially and racially exclusionary world of fashion, he is insightful and unrelenting, demanding recognition by calling out discrimination and producing work at the highest level. “When I wanted to get into fashion, everyone would bring up The Row and how they started withT-shirts. I didn’t want to start with a T-shirt. I love merch, but we did merch as a punk answer to us being told we can’t work at Louis Vuitton, Versace, Nike. Merch started as one of the only things we could control,” he says. “When we did our first fashion show, in crocodile and all these exotic fabrics, there was just a block, like, ‘No,you can’t get in. No, you can’t be involved with this.’ Somehow, I actually had to go back and start with a T-shirt.”

This trajectory has led West to his current philosophy on artistic creation. “I think we can break the class system. This sweatshirt is the blank that we used for merch. In the setting, it feels very elegant, but it’s a very simple cut design—all of the energy and ingenuity. It’s so much time that went into finding the simplest version,” he explains.“That’s what artists do; they take everything that’s happening in life and sometimes encapsulate it into an hour and a half of Eddie Murphy on stage, or Dave Chappelle, or 16 bars inside of a verse, or the cut of a sweatshirt or a boot.”

While he’s focused on elevating and developing his latest designs for Yeezy—he details several prototypes, including “packable” boots and shoes made of algae foam and sweaters with no visible stitches—West also says it is time to take things to another level. “I didn’t come in to make merch. I came in to make operas,” he adds. “That’s no knock to merch and no knock to T-shirts, but now it’s time to change the architecture. It’s time to design cities.” He shows me images of otherworldly public housing, his vision to alleviate homelessness. These homes, sprawling in their luxury and minimal in pricing, will be eco-conscious, using water and wind power, and according toWest, are “very close” to availability.

In all of his endeavors, West seeks to bring rudimentary understanding to complex art forms, and he upends convention, holding true to his own artistic instincts. “It feels like only the mavericks believe in themselves,” he says. “Henry Ford, Howard Hughes—they had to push for what they wanted to present.” West banned the use of a script for his new opera because he felt it was too restrictive. “I told them you’re not allowed to give that script to anybody because that’s a form of education that holds people back—it’s literally impossible for me to read through,” he says. “So how is it that it’s difficult for me to read that script, but I can put on an opera? Well, they’re saying you have to create in a certain way, but you can create at this level by approaching it in a different way.”

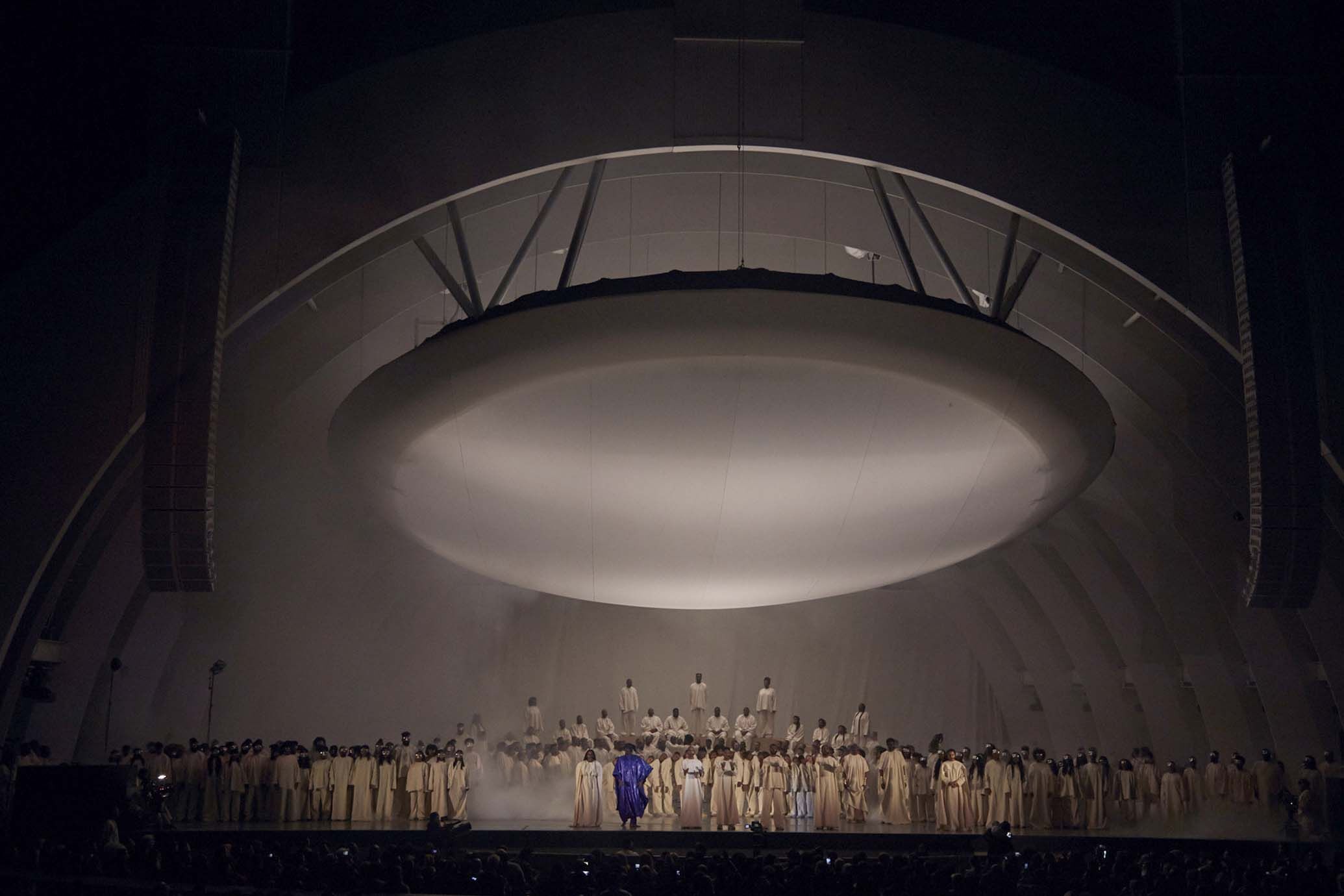

Inspired by the story of the late Babylonian King, as told in the Book of Daniel, the Nebuchadnezzar opera—directed by West’s longtime collaborator, the Italian contemporary performance artistVanessa Beecroft—weaves personal testimony with Latin arias and biblical history. Near the completion of Jesus is King, West felt a connection to the ruler who went mad and had to humble himself before God. “I felt a parallel to my story when I first heard the name Nebuchadnezzar because I’ve had so much ego in the past—this Muhammad Ali-type of ego, this Ye-Yeezus conversation,” he says. It is that infamous ego and other struggles that have made all of his success not without controversy. Leaning forward, he says, “Now thatI’ve given everything up and I gave it all to Christ, I understand that it’s not me—it’s God—and only through God am I allowed to have these blessings, these visions, and this ability to lead inside the fields of music and apparel and architecture.”

Our conversation is littered with tributaries of this theme. God has changed him. God has led him towards a new path. God has granted him abundant blessings and “energized” clarity. “It was all in God’s plan,” he says of his tumultuous last few years. Following a critical reception of Yeezy Season 4 and the terrifying ordeal of his wife, reality star Kim Kardashian, being robbed at gunpoint in Paris in 2016, West suffered several public breakdowns and faced backlash on social media before seeking help. “Today, three years ago, was the day I stopped the Pablo tour and went to the hospital the next day,” here calls. “So the first day of the opera is this new frontier for a platform for creation, for me and for the world.” With plans to bring the opera to cities around the world, he says, “I know the opera isn’t new, but this present-age culture, I really envision these operas as the new place for people to get dressed up, for people to bring their families, for people to anticipate and be inspired, and also as ways to tell Bible stories and be in service to God.”

His venture into opera is an extension of his Sunday Service,which he began last year as weekly private music sessions in Calabasas. Sampling Baptist-church festivities, these praise performances feature sermons and music, his own mixed with popular songs and Christian themes. In April, the private festivities became available for public consumption. Performing at Coachella with a sprawling choir and then taking the ever-growing religious gatherings on the road to Chicago, Wyoming, Dayton, Ohio and to televangelist Joel Osteen’s megachurch in Houston, Texas, West has revealed a changed persona.

“I was a self-centered human being, but I wanted to give my vision to the world and do things to push humanity forward. It wasn’t until I was humbled by God and really beat up and brought through mental institutions, society, getting canceled, all that, that I realized everything is in service to God,” he says. “How can I be in service toGod, to Christ, while being a good husband, a good father, a good friend and a good founder? Through that I’m finding prosperity this year. For the first time in my life, I’m finding true joy and peace.”

As I sit in the audience at the Hollywood Bowl, the opera reminds me vaguely of my childhood. There are men in well-ironed chinos wearing glossy Yeezy Boosts. Others strut past in oversized hoodies and fitted caps. One, in his early twenties, races to his seat and slushes back beer. “Bro,” he says to a similarly-dressed companion, “it’s like a hypebeast church.” When thundering baritones channel “Mo Bamba,” I watch slews of audience members rise and move in jagged rhythm. Many sit, startled-eyed, trying to absorb the scenes. At the end of the performance, almost every hand sways high in the sky.

This story was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of LALA Magazine.

in your life?

in your life?