Over the last 20 years, I’ve been fortunate to engage in dialogue with architects and museum professionals about the urgency of reimagining museum experiences.

In the early 2000s, while based in London and managing the studio of a future starchitect, I traversed Europe visiting contemporary and historic art spaces. In the summer of 2006, I joined the senior leadership team at the New Museum under director Lisa Phillips, working alongside newly appointed curator Massimiliano Gioni. In late 2007, we opened our doors on Bowery, and the SANAA-designed building instantly became an iconic downtown landmark.

I’m relieved that we are moving away from the architectural gymnastics and skewed exhibition walls of the early 2000s, replacing them with empathetic strategies prioritizing artworks and visitors. MoMA, New York’s blue-chip institution nearing its 100th anniversary, devotes substantial square footage to visitor amenities, to the extent that today’s museum typology could be classified as a subset of the hospitality industry. The Midtown establishment, which welcomes 3 million visitors annually, offers four restaurants and cafes, a seasonal bar in the Sculpture Garden, two retail spaces designed by Gluckman Tang totalling 8,000 square feet, and several atrium lobbies capable of hosting 1,000 guests for receptions, parties, and family festivals.

In a recent public talk, OMA’s Shohei Shigematsu summarized how designing museums has become increasingly complex. Historically, museums evolved from salons to multi-room galleries, eventually expanding into architectural landmarks displaying vast collections. In the last two decades, a new and amorphous emphasis on community engagement has dominated client conversations. How do we design for something fluid and constantly evolving, but which requires structure?

SO-IL’s Florian Idenburg echoes this shift. His approach to designing museums, he tells me, is to view them as catalysts rather than containers. “Spaces can invite participation rather than dictate behavior,” he says. “At the Williams College Museum of Art, which is currently under construction, we’re designing an open structure that can evolve, hosting shifting curatorial strategies, new forms of learning, and community engagement.”

There are traditional standards for gallery sizes and ceiling heights, but no universal formula when designing for community engagement. Below is a survey of five of my favorite architectural strategies that transform visitor experiences in fresh and unexpected ways.

Underground Museum, Los Angeles (closed) and Storefront for Art and Architecture, New York

At the recently opened Venice Architecture Biennale, the United States Pavilion’s “Porch: An Architecture of Generosity” exhibition explores the American porch as an architectural connector. It expands its definition from a protected area in front or behind a dwelling to encompass stoops, coffee shops, and other thresholds that welcome the public. Akin to the porch is the storefront—a facade that welcomes any visitor without judgment.

Founded in 2012 by artist couple Noah Davis (who died in 2015) and Karon Om Vereen-Davis, the Underground Museum was situated on an unassuming street of carpet stores and tattoo parlors. Its nondescript storefront in the Arlington neighborhood of South Central LA, opened into an intimately designed bookshop. Part salon, part meeting space, it was a hangout for local teens and prominent Black creatives. The bookshop functioned as an accessible threshold, welcoming visitors with warmth and informality, allowing a comfortable, mental respite before experiencing emotionally layered and complex artwork.

While the UM leveraged the anonymous facade as a democratizing tool, New York’s Storefront for Art and Architecture uses its facade as social sculpture. Designed in 1993 by artist Vito Acconci and architect Steven Holl, the wedge-shaped Soho gallery features 12 hinged panels that open and close in dozens of permutations. The facade blurs the boundary between interior and exterior, with the institution hosting inventive activities from paella dinners to lowrider festivals celebrating Chicanx culture. The sidewalk becomes a welcome mat, the building a generous invitation.

The New Museum’s cultural incubator NEW INC, New York

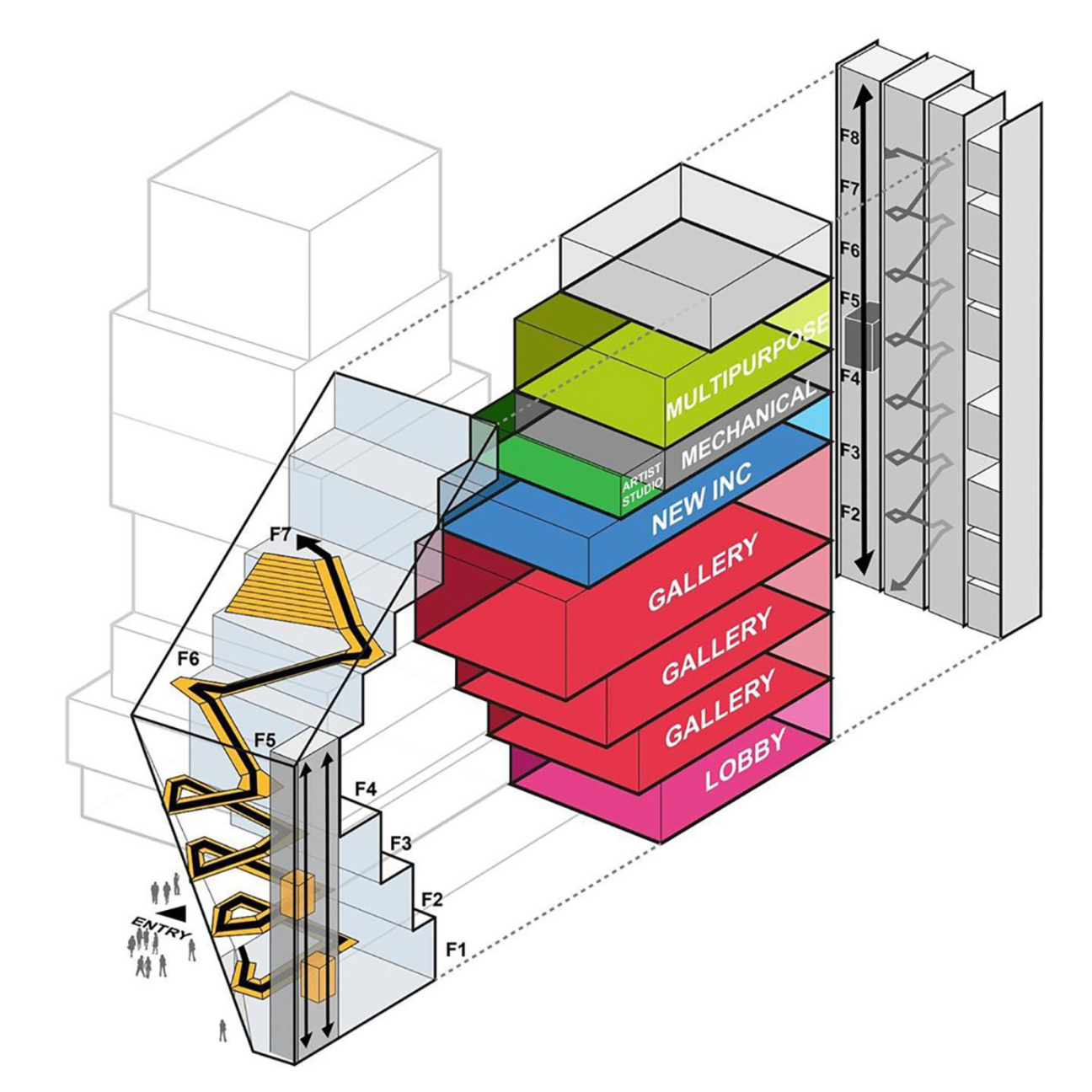

In 2008, the New Museum purchased a light manufacturing building adjacent to its recently opened SANAA-designed home on the Bowery. In 2014, NEW INC, an incubator of 100 creative practitioners, moved into the adjacent building’s renovated second floor designed by Brooklyn studio SO-IL. Later this fall, NEW INC returns with the New Museum’s expansion by OMA and Shohei Shigematsu. What makes this model distinct is how the museum defines community: It’s an expansive group of creatives whose cultural production doesn’t always adhere to traditional “fine art” paradigms. NEW INC reimagines museum engagement, offering support for entrepreneurial creatives working toward sustainability. By situating such programs within its walls, the New Museum elevates and lends institutional legitimacy to these creatives, positioning often unseen practices as worthy of display and public inquiry.

21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan

By museum standards, the floor plan of the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, by SANAA’s Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, breaks all rules. The museum’s all-glass ring surrounds a constellation of rectangular galleries and public spaces, with no single path or hierarchy. Galleries tend to be in the center, and the outer ring of rooms serves as a kids’ studio, nursery, art library, theater, cafe, and store. The lawn surrounding the Museum is a public park conducive to movement and family workshops. Visitors may choose one of the four entrances to discover galleries, duck in and out of rooms, and reconnect with slices of sky via several interior courtyards. They can even attend a town square meeting in the People’s Gallery. This meandering journey transfers agency from the institution to the visitor.

Greater Grand Crossing, South Side Chicago

While Kanazawa’s galleries are scattered within a single building, Theaster Gates’s model in Chicago disperses cultural engagement across an entire neighborhood. Over two decades, the artist and social innovator has acquired more than 60 properties in Greater Grand Crossing, transforming abandoned buildings—including a former crack house and a bank—into cultural hubs: a cinema, library, archive, listening studio, garden, and production space. By preserving history and memory, Gates honors the people left behind and forges a future where boundless community engagement is at the core of urban design.

Crystal Bridges Museum, Bentonville, Arkansas

What does creative community engagement look like in a region where traditional art institutions are sparse? The answer: If you build it, they will come. Much like Kevin Costner in the 1989 film Field of Dreams, Alice Walton and her family must have heard this mantra when they envisioned the Crystal Bridges Museum. Opened in November 2011, this Bentonville landmark designed by Moshe Safdie welcomes nearly 800,000 annual visitors, more than 70% driving in from across Arizona, Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma. The museum is nestled between two ponds and surrounded by five miles of hiking trails, advertised as one of the institution’s many offerings. The museum’s restaurant, Eleven, is situated on a bridge that floats above water. While critics may argue that Walton’s vast resources make Crystal Bridges an outlier, its success is undeniable. General admission is free, and nearly half of its visitors are first-timers, a strong signal that the museum meets a real and widespread desire for local access to art. In a part of the country underserved by cultural infrastructure, the museum doesn’t just serve a community; it creates one.

in your life?

in your life?