All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt, poet and filmmaker Raven Jackson’s feature debut released last year, slaloms its way through five decades of its protagonist Mackenzie’s life in just under two hours. Shot in rural Mississippi, where Jackson’s mother and grandmother grew up, the film revels in the emotional topography of its landscape. Here, Jackson singles out Carlos Reygadas’s 2007 film about a Chihuahuan Mennonite community and speaks to how it shaped the spirit and sounds of All Dirt Roads.

CULTURED: What have you learned about your own film since it's been released?

Raven Jackson: It's an interesting thing to, at this scale at least, put work into the world and then come across how people engage with your work. For instance, when the film started to show, the language of being interested in the body came up a lot. Even in my short film Nettles, that's there. It's interesting to see words put to things that are almost the water you're swimming in.

CULTURED: If we go back to 2018, what inspired you to start writing about Mackenzie, who we follow through decades of her life, and to locate it in Mississippi?

Jackson: I knew from day one of starting this film that I wasn't interested in a traditional plot-driven film. I really wanted it to be an experiential, evocative film that almost washed over the audience and that really spoke to the senses. I know my background in poetry informed my interest in doing in Nettles. I explored form and structure, and that's a short. I knew I wanted that in a longer film. I took a lot of photographs before I wrote a page of a script because I really needed to be in the world. I'm from the South and I knew the place, but I needed to feel it and really be in it for a bit.

CULTURED: Other than the photographs you were taking, what references to Southern culture were you looking at for this film?

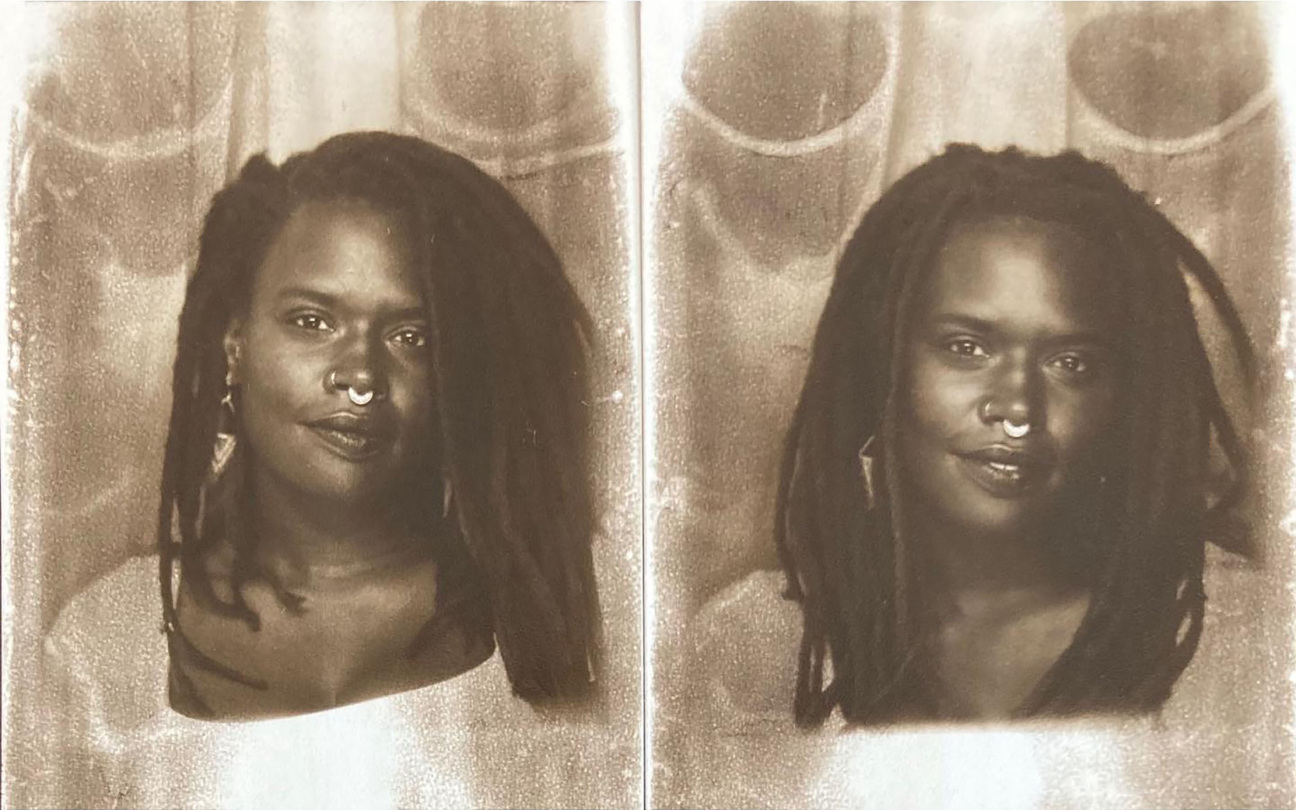

Jackson: When I first started the project, I thought we would shoot in Tennessee, but we ended up shooting it in Mississippi because we found a great location there and it made sense to build a production around that. It ended up being a beautiful gift because my mother is from Mississippi and so is my mother's mother. I turned to a lot to my grandmother's photo albums in the research and development phase of the film—the colors, the textures, the outfits people are wearing, the landscapes. Those photographs are very tactile. They had a lot of what is at the heart of this film.

CULTURED: What role has visual art has played in your formation as an image-maker and writer?

Jackson: The evocativeness of Todd Hido's photographs. Some of his photographs really stay with me—the treatment of light. There's ones that I can just look at and I'm in the mood to create. I'm in the mood to come to the page.

CULTURED: How did you first come upon Silent Light and what was your first impression of it?

Jackson: I went to New York University for graduate film school, and I was a graduate assistant in a sound class. Ian Harnarine was the professor. He played the opening scene of this film, and I was blown away because the opening scene is just darkness. You hear nature, you hear animals, and then slowly you see the sun coming into the sky and you can see. But the patience, the wonder of a new day, all of this richness of sound really stayed with me. I remember getting the film soon after that and watching it and just really resonating with it.

CULTURED: Can you describe for us what role sound plays in the film?

Jackson: It's about letting the sound be the centerpiece of a scene, trusting the weight it can carry to [the point] where I don't need to have anything else explained to me. There's one scene [in Silent Light] that's coming to mind where you see the protagonist sitting at a table and you hear the sound of this clock that's on the side of the wall. You just hear the rhythm of it. This character, as he becomes emotional, the sound of that clock is just saying so much. Silent Light really trusts what sound can do. It feels like it's bringing me there. When sound is treated with such reverence, it just can aid so much.

CULTURED: When did you first connect it to All Dirt Roads?

Jackson: I knew from the beginning stages of All Dirt Roads that I didn't want to have a lot of dialogue in the film. I wanted to use other means to communicate the emotionality of the characters. How do we communicate through silence? Through gesture? And if I'm saying silence, what are we hearing in that silence? A silence that still has the world in it—the cicadas, the insects. The film is very close to nature. What does the rain sound like and how does that differ from the rain in a different scene?

CULTURED: Did you share Silent Light with other people in the cast or the crew, or did you keep it to yourself as a sort of inspiration?

Jackson: When we were pitching [All Dirt Roads], the film was mentioned. Jomo Fray and I, the cinematographer, we spoke about it. He knew this was an inspiration for me, and we watched scenes and moments and we definitely had conversations about it to really get at and give language to what is working, where the resonances between Silent Light and All Dirt Roads can be.

CULTURED: If you could ask Carlos Reygadas something, what would it be?

Jackson: I'd be very curious how long in the post process does he allocates for sound design. What does that process look like for him? Does he take days away? And what does his process impose to not only give himself enough time, but to keep his ears fresh? I found that I didn't give myself enough days, so I'm always curious.

in your life?

in your life?