Robert Eggers is best known for creating macabre, otherworldly films like The Witch, 2015, and The Lighthouse, 2019, set in his native New England. But his latest feature, Nosferatu—loosely inspired by Bram Stoker’s Dracula—tackles a distinctly European tale. Ahead of its release, the director recounts how a little-known German artist named Sascha Schneider helped inspire the look of The Lighthouse.

CULTURED: What work of art would you like to talk about today, and what film would you connect it to?

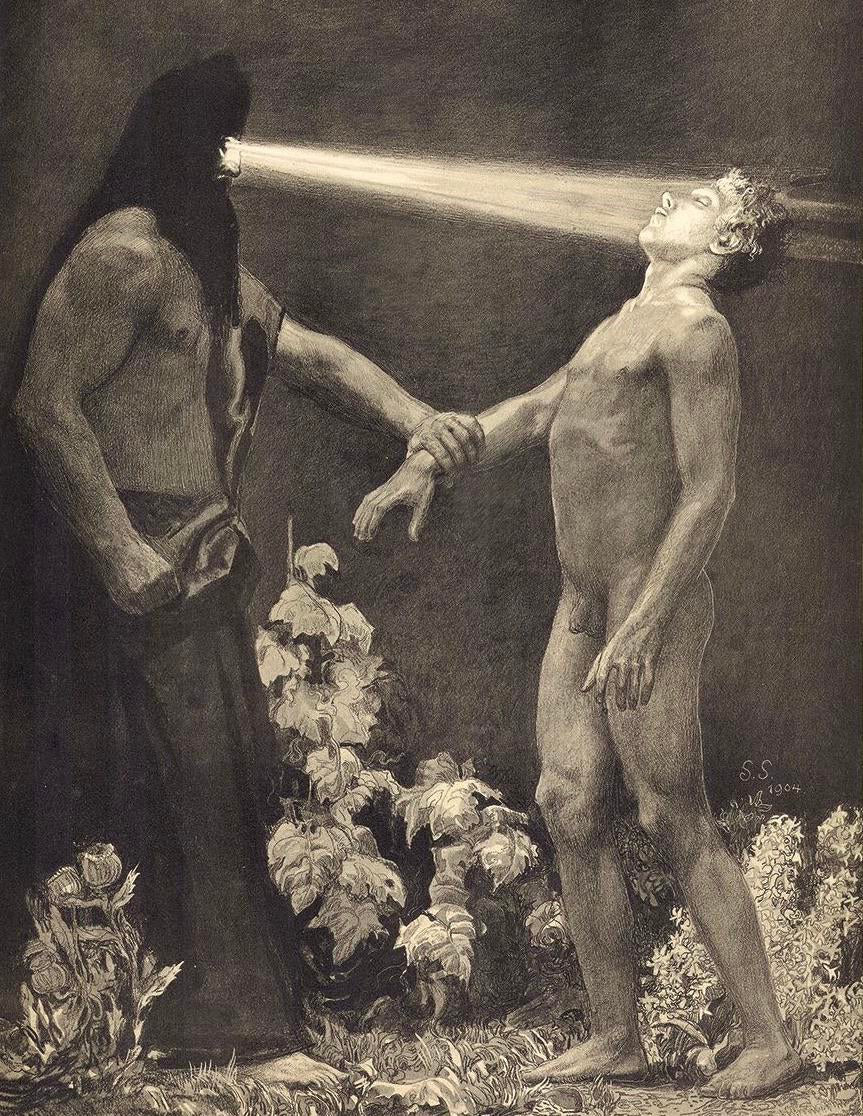

Robert Eggers: I’d like to talk about Sascha Schneider’s Hypnosis, 1904, in relation to The Lighthouse, but I’ll also talk a bit about other films since The Lighthouse is two films back. With the release of Nosferatu almost a year away, I feel I’d be giving too much away if I went into detail about my inspirations for that film. I will mention that like [F.W.] Murnau and his producer/production designer Albin Grau, I was drawn to Biedermeier paintings and German Romanticism, from Caspar David Friedrich to the Danish-Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl. The Northman had less painterly influences than any of my other films, as Viking-age art is not atmospheric or naturalistic. I could talk about Gotland picture stones, and brooches, but it may come across as far-fetched.

CULTURED: Let’s start by fleshing out the premise and tone of The Lighthouse. How did you land on its vibe?

Eggers: Many of my films start with the atmosphere first. Certainly, The Lighthouse did. I pictured the boxy aspect ratio; the high contrast black-and-white; the dusty, musty environment; pipe smoke; facial hair; and sweaters. This would have made me drawn to [Andrew] Wyeth’s rotten clapboards and lighthouses, not a European Symbolist. Ironically, Hypnosis is something else.

When my brother and co-writer Max [Eggers] and I had the first pass of the story down, we asked ourselves what fairytale or myth our story was most like to amplify our knowledge of that myth and integrate it into the film. Prometheus stealing fire was clear to us, but the story of Proteus was something that surprised us. When we integrated more classical mythology into the film, we were looking hard at symbolist painters, Jean Delville and Arnold Böcklin especially. But Schneider’s Hypnosis was clearly meant to be a set piece moment for this film.

CULTURED: I know you have a very research-intensive process. You've said that you could have been an archaeologist. What kind of art historical excavation did you do for this film?

Eggers: For every film I make an extensive look book that’s made up of mood boards of paintings, photographs, and more. This is shared with all the heads of department and cast, and is the bible for the look of the film. I give the production designer and the costume designer thousands more images. For The Lighthouse, the material world of the film was mostly based on photographic research. But for The Witch, while we were working with specialists in experimental archaeology who were experts in 17th century English and New English agricultural lifestyles, many paintings were very influential. Some works of Rembrandt, for example The Girl with the Broom, ca. 1651, and many works by the brothers Le Nain who depicted lives of poverty, and of course works of witchcraft by Hans Baldung Grien, Salvatore Rosa, and [Francisco de] Goya who we directly reference at the end of the film when the witches levitate.

CULTURED: What genres or eras of art history would you say you’re most drawn to? Any artists that stand out as continual reference points?

Eggers: [Albrecht] Dürer is my favourite artist, and I am very fond of the Northern Renaissance in general. I look at Dürer’s work very often, and think about it all the time. Every day, probably. I tend to dive deep into the artwork from the period of the film I am depicting, but Hyman Bloom, Odd Nerdrum, and occultist painter Denis Forkas defy their periods and are painters whose work I am very inspired by.

CULTURED: How did you first come upon this work of art? What was your first impression of it?

Eggers: I think I came across Hypnosis on Tumblr. I’m not sure. But certainly some sort of banal online discovery. Obviously, it's a very striking nightmare image. The atmosphere is truly dreamlike and the artist is of course depicting an impossible moment. Like the victim in the image you are immediately drawn to the light, and then next the grip of the god-like villain, and then to the victim’s genitals, which makes him seem all the more vulnerable.

CULTURED: When did you know Hypnosis would work its way into this film?

Eggers: It was my brother Max who suggested we just take the plunge and do our own riff on the engraving. When Pattinson’s character has totally lost his mind, he has this vision of Dafoe naked, before him with the light coming from his eyes, gripping his shoulder, and Pattinson on his knees in awe and fear before him. The composition is slightly different from Schneider's, but Willem and Rob's body positions are still quite classically positioned. Hopefully, the nightmare is still intact, and the homoeroticism as well. In my shot, with the oppressor being nude, his naked body becomes a symbol of power instead of vulnerability. The victim in Hypnosis seems indeed hypnotised, unaware of his condition, whereas Pattinson is all too aware of the horror he is experiencing.

This conversation is part of a series in which CULTURED asked filmmakers to reflect on a work of art that exposed them to new ways of seeing—and set the tone for a recent project. For more insight, read Lulu Wang on the Singaporean photographer whose work inspired both The Farewell and Expats, or Reinaldo Marcus Green on how Basquiat helped him understand Bob Marley.

in your life?

in your life?