During a brainstorming session with her creative agency A Vibe Called Tech, Charlene Prempeh discovered Ann Lowe, the Black designer who created Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding gown. It was no accident that she had never heard of her before. In 1961, Ladies’ Home Journal reported that the gown had been designed by “a colored woman dressmaker,” but did not name Lowe. The designer’s story prompted Prempeh to consider the many influential Black creatives who had been not passively overlooked by history, but willfully excluded from it.

And with that, Prempeh set out on the journey to write her debut book, Now You See Me: An Introduction to 100 Years of Black Design, which chronicles 100 years of Black design. The tome covers fashion, architecture, and graphic design, replete with archival photos, biographical information, reflections from contemporary figures, and Prempeh’s own experiences as the founder of a creative agency that works with clients from Gucci to Frieze. CULTURED spoke with the author ahead of the book’s release today.

CULTURED: Your debut book, Now You See Me, explores 100 years of Black design. Why did you feel like this was the right moment for a publication like this?

Charlene Prempeh: I'm not sure if this is the right moment in any discernible way—the importance of these stories and the work of the individuals featured has always been essential. What is interesting about the book coming out now is that there is a certain amount of lethargy around diversity in the creative space and overt hostility in many political circles. It's important to remind ourselves of the historic role that race has played in different spaces so we can enact change that is meaningful and enduring.

CULTURED: Collaborating with brands like Gucci and institutions like Whitechapel Gallery, how do you meld the mission of A Vibe Called Tech with that of your partners?

Prempeh: We try to work with clients who are genuinely committed to reaching a diverse audience and who want to tell stories that are relevant and uncovered. We're not trying to convert brands to our way of thinking—what we're trying to do is come together in partnership to make something that is conceptually and creatively exciting.

CULTURED: Now You See Me highlights the story of Ann Lowe, the Black designer who created Jackie Kennedy’s wedding gown. What drew you to Lowe’s story, and how did you navigate bringing her experiences to light?

Prempeh: I really wanted to present her as a multifaceted character and not just a victim of high society’s racism. She was a huge creative talent with an obsession with the upper class. She had terrible business skills and an audacious spirit. I wanted to portray all of that.

CULTURED: How did you go about selecting the other individuals featured in the book?

Prempeh: I was looking for people whose stories hadn't been told and/or who emphasized a particular experience of being Black in design. I wanted narratives that illuminated issues that are still relevant now.

CULTURED: In your writing, how did you bridge the gap between historical narratives and modern design perspectives?

Prempeh: In a way that is very problematic, there wasn't really a huge gap to bridge. The issue Ann Lowe had with not being recognised for her work is still a problem with Black creatives. The complications of respectability politics that [architect] Paul Revere Williams suffered is still something that some Black designers have to navigate. The industry still struggles to recognize Black female genius in the vein that I discuss [cartoonist] Jackie Ormes's work. Progress has not been a linear trajectory.

CULTURED: As the founder of A Vibe Called Tech, you “approach creativity through an intersectional lens.” What does that look like on a practical level in your day-to-day work?

Prempeh: It means that in developing strategy and in execution, we consider the perspectives of voices that historically go unheard. One of the things that marks our agency as different is that we tend to accompany any visual story with details on how the narrative was developed in the form of interviews, essays, or podcasts so those consuming the work can go beyond the aesthetic to understanding the lives of people featured and the cultural relevance of the story being told.

CULTURED: How do you hope readers will continue this conversation or shift their thinking on the topic?

Prempeh: The scope of the book is really wide-ranging so I see it as a starting point for discovery. My biggest joy would be if this book becomes a springboard for people to go off and do their own research or even just to stop and think about how some of the issues raised play out in their own world.

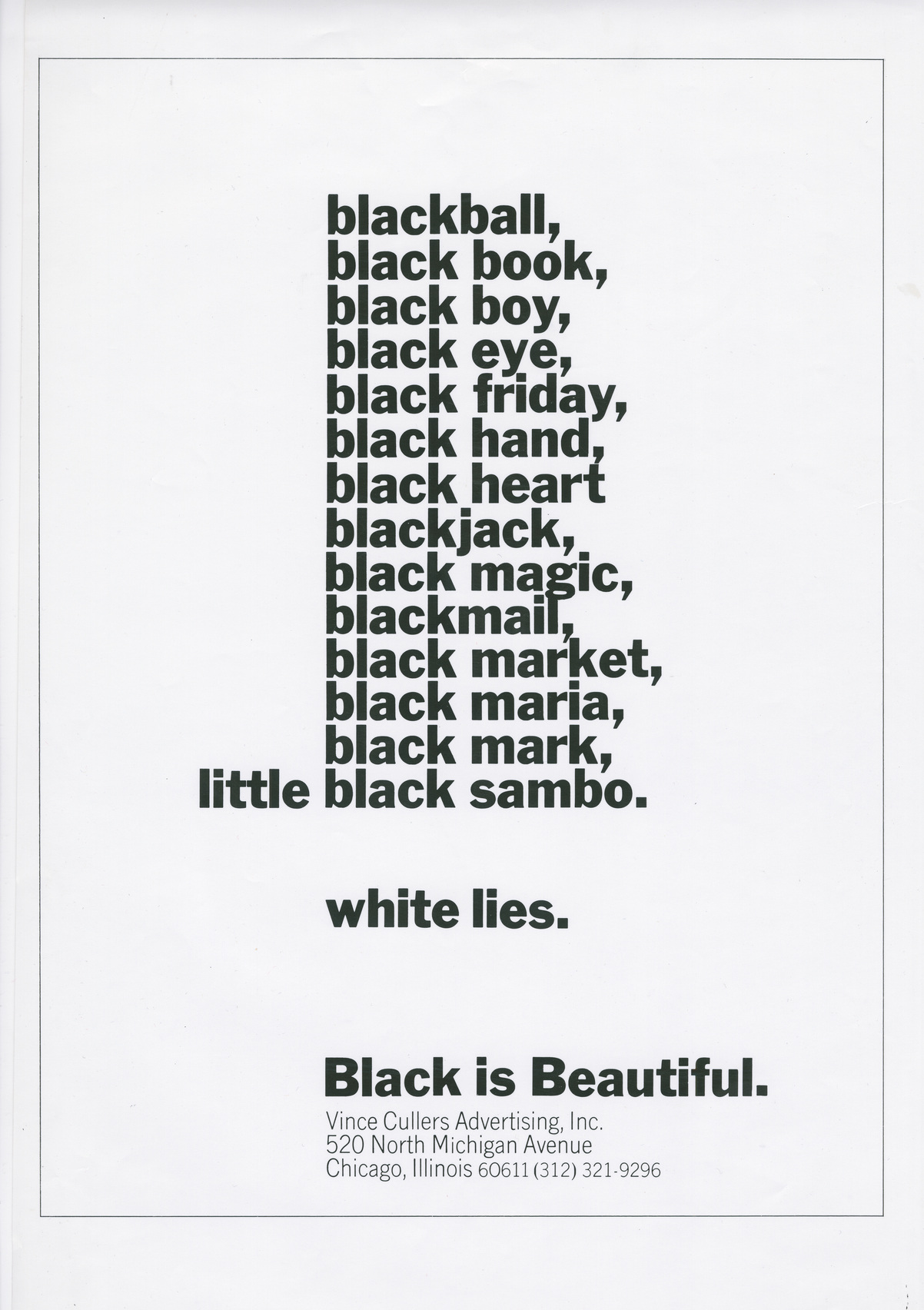

CULTURED: In discussing “mainstream” culture, you pose questions about who defines what is “normal” and whose opinions are most accepted. How does language play a role in marginalization and erasure, and how do you approach this subject in the book?

Prempeh: Language and categorization is as important as aesthetics in the design world. Whether your brand is regarded as “luxury” or “streetwear” isn't a matter of semantics—it determines the trajectory of your business and defines where you will and will not be visible. Associating Black designers with words that pigeonhole their work into a realm that is somehow “other” by describing it as “ethnic” or “urban” or “emerging” (even if it's been emerging for 10 years) minimizes the creative capital of Black design and blunts the nuances of the work. It was important for me to address the language used around “genius,” “polymath,” and “mainstream” at different points in the book and ask why Black designers, and especially Black female designers, are so often overlooked when applying these labels.

in your life?

in your life?