The art world doesn’t interest Simone Fattal. The Syria-born, Lebanon-raised painter and sculptor has spent the last decades in a different temporality, experimenting with the primordial nature of clay and the ancient texts—like the Epic of Gilgamesh, The Iliad, Works and Days—that fuel her sculptural archaeology. The ceramic civilizations she spawns give these epics a new life, forging space in a “headless world” to consider humanity’s odyssey.

This spring, the artist's practice is the focus of shows at Karma International, Ashkal Alwan, and the Sharjah Art Foundation, and a lecture at the Louvre. In the midst of a residency in Provence, the 81-year-old called CULTURED to talk about her own epic life.

CULTURED: When did you first know you wanted to be an artist, or that you wanted to work in the art world?

Simone Fattal: I never wanted to be in the art world. This is not something that appeals to me, even today. It’s making sculpture and painting that is wonderful for me. When did I really imagine that I would be a painter? It started in 1969 after I had studied philosophy. As a child, I never imagined being an artist. I wanted to be a writer. I was a reader, not at all a painter and sculptor. It came to me by chance because I had many friends that were painters. It's a really wonderful way of living, of searching, of discovering, of expressing all that one needs to do.

CULTURED: What are you interested in learning right now?

Fattal: I love to work in ceramics most of all because, when you work with clay, you work with a very primordial medium, which is earth. Working with clay is actually the only artistic process that allows you to work with the primordial elements—air, water, and fire. It’s not the same with painting, it’s not the same with bronze, it’s not the same with any other. When you work with clay, there is water in it, and then it has to dry in the air, and then it has to go into the kiln where it goes through the real transformation from simple earth into an actual piece of art. Without knowing it consciously, it certainly is what makes it so incredibly interesting.

CULTURED: You worked in painting before turning to clay. Is there a moment that you realized you were becoming an artist?

Fattal: The minute I started painting I accepted I was going to be an artist. It’s inherent. What is the difference between an artist and someone who is not? Everyone can paint or work with clay, but the fact that you go on with it, that you are making it your life, this is what makes you an artist. I knew that I was going to go on with it, you see? That was of paramount importance.

CULTURED: Was there ever a moment where you thought about or considered leaving your practice behind?

Fattal: When I left Beirut and went to the United States, I had to put all my work in boxes. I had to put it aside, and that was a traumatic experience, of course. So when I arrived in the U.S., I just didn’t want to paint. The Bay Area is just so wonderfully beautiful, but I didn’t know it. I had nothing to say about it; it wasn’t mine. After some time, I had the idea of doing a publishing house. I published for a long time before I went back to my artistic practice. I arrived in 1980, and I started the Post-Apollo Press in '82. When I felt that the Press could somehow stand on its own feet and did not need my 24 hour care, I went back to my art practice and took up sculpture. I went back to school because I couldn't work at home, especially not with clay. Those were wonderful years, actually. I discovered a whole new way of expressing myself. Sculpture was a discovery and was, in a way, very easy. It was an exhilarating thing to do. Then a few years ago I started painting again, so now I do both.

CULTURED: How do those two parts of your practice inform each other?

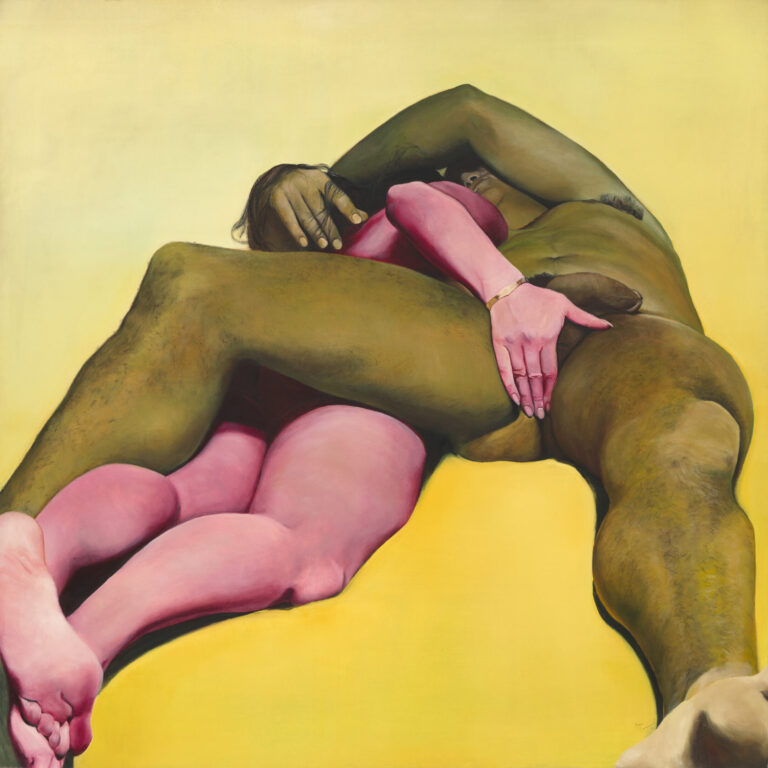

Fattal: It doesn’t come from the same place. When you look at my painting, it is extremely [different] from my sculpture. They don’t say the same things. My painting is [mostly] landscape, abstracted landscape, and my sculpture is about people, people who embody ideas, more than anything visual which surrounds us. It is not about something that is there; it is something that comes from an intellectual choice.

CULTURED: And what conversations today are informing the sculptures you are continuing to make?

Fattal: It very often comes from my readings, from the poetry I read. Those who have influenced my work are the classic, old texts like The Iliad, The Odyssey, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and so on. Really that’s what I think of when I make my—I can call them my people—standing figures.

CULTURED: Do you see these standing figures as linking these epics of the past with the epics of the present?

Fattal: I see them as a past that has to be understood today, that has to be revived today. I use them as a means to talk about what we are living today, really. And I revisit all these past figures because I feel I need to understand them, you know? These are all things that we read at school, and we don’t understand them. That’s what interests me.

CULTURED: It's an act of translation.

Fattal: When you’re making a sculpture, it’s already a translation. A translation of what you have in mind, of what you want, of what you are. Everything is a translation. Thinking is a translation. You think, but in order to grasp your thinking it has to go from the cell into language. What would we know about ancient Egypt or Greece if it was not translated into English or French or whatever language we are speaking? In my publishing house I had a lot of translations. I published French books, everything else was published in English, French, German, Arabic… It’s essential because you need to know all the literature of the world as much as possible. We need to know as much as possible. Man is here to know.

CULTURED: What is the artist's role in the contextualization and dissemination of this knowledge?

Fattal: What the artist does is share by putting it out there. The work is a discovery and what he has discovered, which is this painting or this sculpture, he puts it out there for people to learn something. Look at the museums, they are full of people because they are looking for something to learn. It doesn't have to be a very serious thing. It can just be the joy of looking at colors, or colors used in a different way. We have to also accept that we want to be entertained, we want to have nice things to look at.

CULTURED: What's the hardest part of being an artist?

Fattal: The work. It can be very hard, not only physically. You have to go places. It’s not an easy thing to do, otherwise more people would have done it. It demands extreme attention to everything. You put your whole life on the table when you are working.

CULTURED: Do you think you have to give up something to become an artist, or to stay an artist?

Fattal: You give up a lot. You give up being comfortable. You offer yourself to criticism. Not just someone who says, "Oh this is bad." It is a very deep way of criticism. But it’s worth it. It’s difficult to produce a painting, but once it’s done and you think it’s okay, it’s worth all the trouble you’ve gone through. That’s why you go on with it because it’s worth it, and it makes you happy. Especially if someone else likes it then it’s very, very nice.

CULTURED: What makes it worth it? That moment of seeing the painting or the moment of seeing someone look at the painting?

Fattal: You have achieved something. You have arrived at the point you wanted, which is to express something very definite. To make a painting you have to have a very clear intention. When you see that you have expressed that intention, you are very happy. You battle, you use your words, you correct, you go back, you erase, and then you’re happy.

CULTURED: You said in an interview, "I hope my work might say to future generations we gave a good fight." And I’m wondering today what you’re fighting for and against with your art?

Fattal: It's a duty for man to be a warrior, to be someone who does his best, who will be doing his duty. He is not going to war. On the contrary, he wants to stop every war. It’s more and more important to do that. It’s a very dangerous world we live in. It seems like it’s a headless world, going its own way. No one is trying to make it stop and think.

CULTURED: If you think about young artists who are coming into this world that does feel so full of obstacles and so confused, what word of advice you would give them?

Fattal: He must have a very clear intention of what he wants to be, of what he wants to do, of what he wants to say, and not be pushed around [by] everything that is going around him. He has to be standing on his own and doing whatever he wants to do in spite of the world and difficulties. The young artist should think for himself and choose for himself.

Working every day is very essential because working brings another work. It’s in working that you find your answers and your way. It’s not by just playing around. Many, many great artists work better and better, and why is that? Take Henry Moore, take [Paul] Cézanne, take [Pablo] Picasso, they were great at the beginning but they were extraordinary at the end. You know your tools, you know your time, you know yourself. That’s the first thing we learn in ancient Greece, that we have to know ourselves. It is the best advice I can give.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with female artists over the age of 75. To read more, take a look at our stories with the avant-garde Pippa Garner, Brazilian sculptor Sonia Gomes, and mixed media pioneer Betye Saar.

in your life?

in your life?