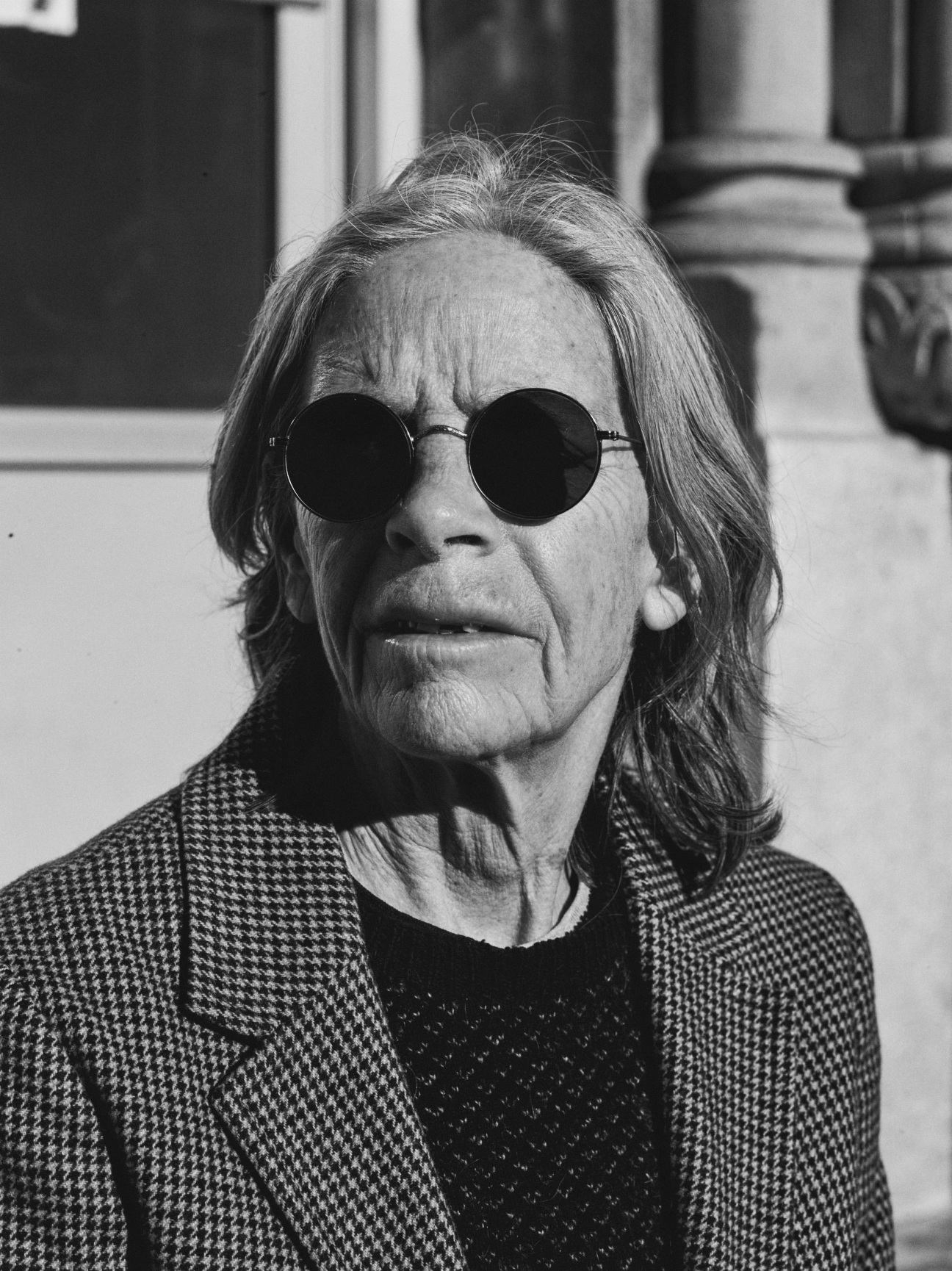

In a 1999 essay called “How to Write An Avant-Garde Poem,” Eileen Myles remembers, “When I first started writing poetry I thought it was a miracle that I could stay home and tinker all day with two words, or three… There was a grand and humble freedom, something utterly wild and private about not going to work, and if the phone rang work stopped and I could go out for days and return to the miracle of the poem emerging word by word on my typewriter. Poems stayed.” Since moving to New York from Boston in 1974, Myles has run for president, published 20 books, been awarded a Guggenheim, toured with Sister Spit, inspired a TV character, and become the best known face in the fight against the destruction of East River Park. As they've incorporated new identities and achievements, one thing has remained the same: Eileen Myles is a poet. And not just any poet, but one that has restlessly and playfully continued to reinvent the role of the public intellectual with their eager, polychrome odes to living and bouncy, conversational reading style.

Myles's poetry is best understood as an itch—for a sense of home in the world around them—and an expansion of the seemingly banal to the globally relevant. Their newest book of poems, a “Working Life,” is out this week and speaks to the "sweet accumulation" that makes up a poet's practice and life. CULTURED sat down with the writer, who lives between New York and Marfa, in an East Village community garden to talk about the importance of a first draft, finding freedom in transit, and essential writing instruments.

CULTURED: In “April 15,” one of the poems in this new collection, you write that your last two lovers were not interested in who you are but what you are. Eileen Myles, who are you today?

Eileen Myles: I just came back from Berlin yesterday, so I’m home and it feels really good … You know how it is, you come back to New York and just hit the ground running … I feel like today I’m a celebration of ritual. When I come back to my apartment, I’m so aware of my habits. Every time I turn to do something, it’s in the right place because I live there and I live like me … So that’s today. I’m a real happy creature of habit. I like what I did and what I’m doing.

CULTURED: In a 2009 interview, you compared poetry to a valve. When did the valve for the poems in a “Working Life” start pressing open?

Myles: Before the events of 2020 … Part of the thing about writing poems over time is that it starts to be a part of your rhythm. Every three or four years, there's an accumulation, and it feels like a book. Sometimes poems resemble ones I've written before, but the person who's writing them feels like somebody different. This book feels nakedly different to me. The title was kind of a joke I had with myself, which I think poetry often is. I was putting all of my new poems in a file holder, and at some point I wrote “a ‘Working Life’” on the outside. I was thinking, This is not a working model, it’s a working life.

CULTURED: What’s changed that makes this one feel nakedly different?

Myles: I've turned a corner. I'm 73—I have all the things of a person of that age, and otherwise I don't identify with it at all. I think probably for about five years, I had this thought that I was turning a corner and not even knowing what that meant. But I did feel like in some way, whatever I was doing, I’d better be doing it now. I'm playing for keeps; I don't want to have a whole lot of extraneousness to my life.

CULTURED: Keeping it in the folder!

Myles: I know what I don't want in there. Existence is a journey, and I'm definitely on the final third of it, which could be short or long. Chances are that I'm closer to the end of the story than I've ever been. I guess you always are.

CULTURED: What is this book for?

Myles: It's for the value of writing poetry, because that's my practice, but also the value of any practice. The way I got into writing poetry, I was in my 20s, and I was just like, What am I going to do? I always felt kind of ambitious, but ambitious for what? There was a point at which I started to notice that the jobs I had had after college—no matter what the job was—what I was actually doing was writing poems. The book is about trying really hard to notice what you're actually doing and privileging that.

CULTURED: Is it against anything?

Myles: Maybe what anybody else wants me to do. People wittingly and unwittingly are making demands on other people. And I think politics… I don't know that I get to reshape the world, but I'm very aware of the betrayal that it is—in terms of space, rights, and there being any kind of level playing field in terms of people being able to live the lives they need or want to live. One of the pieces in Pathetic Literature is an essay by Simone Weil. It’s about being a Jew who’s becoming a Catholic, but not wanting to get baptized. She wants to be with all the people outside the church. She’s with them. I feel that way about privilege. As I have more privilege, I have more and more desire to be with the people who don’t. That’s what I don’t want to be: inside the church.

CULTURED: This book takes us to many landscapes, like New York, East River Park of course, Marfa, Provincetown, Göteborg, but also liminal spaces like planes and trains. What place does travel have in your life?

Myles: My body gets carried all over the planet, just by dint of having made this choice. It's really funny when you're on a plane, and once in a while you talk to somebody and they say, “What do you do?” And you say “poet,” and they just kind of look at you… A lot of it is about the absolute fact of being conveyed all over the world. I love being on trains and planes because it creates this feeling of freedom. I like being trapped and then finding the freedom inside of something. I don't ever sit in a laundromat anymore, but I remember when I first came to New York, I loved writing in my notebook and reading while I was sitting at the laundromat. I was always worrying the rest of the time about what I was doing and where I was going. I wasn’t worrying when I was at the laundromat.

CULTURED: There’s a line in “Transmission,” a poem of yours from 2017, that goes “just a notebook / and a cunt / and my thoughts.” What do you write with?

Myles: I like writing by hand because there’s this weird intimacy, where the hand and the body and the time and the room and the heartbeat are all synchronized. It’s very mortal. The computer is a little dangerous, especially with poems, because you can instantly start rewriting, and then you lose the first draft. And a poem is really the first draft. You tweak it, you abandon parts of it, but that first draft has to exist. So I carry composition notebooks and legal pads.

CULTURED: Why the legal pad?

Myles: My first job in New York was at a place called Prisoners’ Legal Services, and I was the gofer and a process server … I had access to the stationery cabinet, so I started to take home Pentel pens and legal pads. I still really like a pen that's leaky like a Pentel, and I love the long page of a legal pad—it’s really sexy to me.

CULTURED: Are there any poets you’re reading or in conversation with these days?

Myles: Stephanie Cawley, Òscar Moisés Díaz, Rebecca Shippee, Sallie Fullerton, Will Farris, Christopher Soto, sadé powell, Ashley D. Escobar, hannah baer, Brontez Purnell, Precious Okoyomon, Mick Toma, Emilio Carrero, Liana Svea, Ellery Pridgen, Ama Birch, Brittany Cortez, Evan Lincoln…

CULTURED: You’ve written so prolifically across decades. Other than recent books, where would you recommend new readers to get a start in Eileen Myles territory?

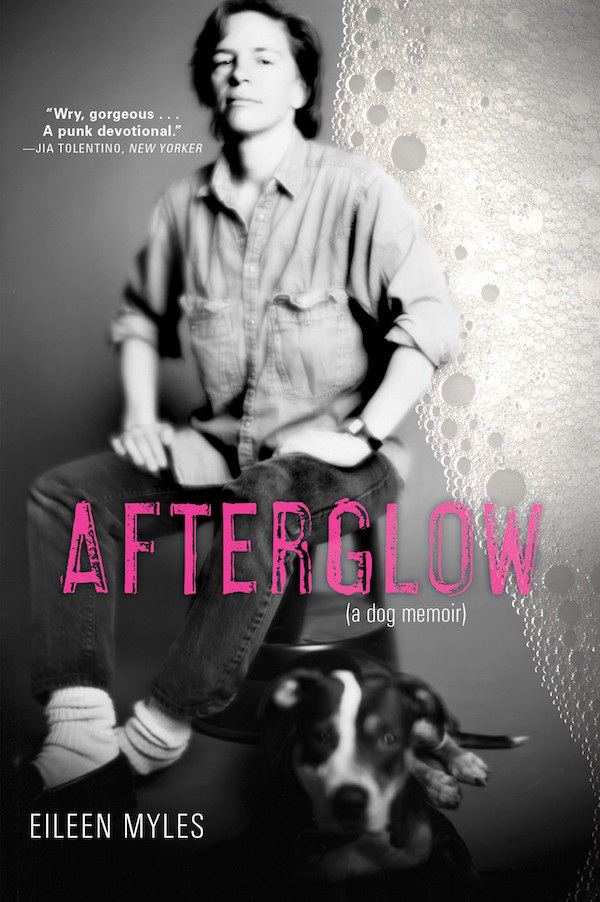

Myles: I think Not Me is always the opening. People really like that book. Chelsea Girls is really obvious. I love to direct people to Afterglow because it's a book that I'm really proud of. I feel like it's my weirdest book. I called it a memoir, and it's the most fictional book I've ever written … I just want that book to be more known, because it was a book that won itself. I really felt stumped and puzzled, and I felt like I kept throwing things out this window. That was the book. It feels very shrine-y to me.

CULTURED: What are you working on now?

Myles: I'm working on figuring out a way to respond to the loss of half of East River Park. I feel truncated in my own response to it; I was buried there for a year and a half working on it. And when they started cutting the trees, I left. My need to go and be the writer apart became really strong, and I succumbed to that. I was very inspired by Terry Tempest Williams who had that cool piece in The New York Times about the Great Salt Lake. She talked about the thing that we all know about, which is the personhood of the lake. I find myself thinking a lot about the personhood of the park, and the personhood of trees. Trees are my favorite alive thing.

One of my favorite endings of a poem in a “Working Life” is in “Mary Queen of Scots”: “The crown / of a tree / see through / poking / over a hill / and I / want / my hands / on the font / I want / I want.” I enjoy saying “I want, I want” because I think poetry is want; it’s desire. But there’s also the “font.” I'm really pleased that Grove Atlantic let me write the cover. It's written in a China marker, one of my favorite instruments. There used to be a butcher across the street from my apartment, and he would give you the meat, and then on this waxy paper, he would grab this China marker and write the price. I've been using them ever since. I swear, it's as much a part of me as my poetry is. In your box of crayons, the black crayon was always the strongest one. And this is the black crayon.

in your life?

in your life?