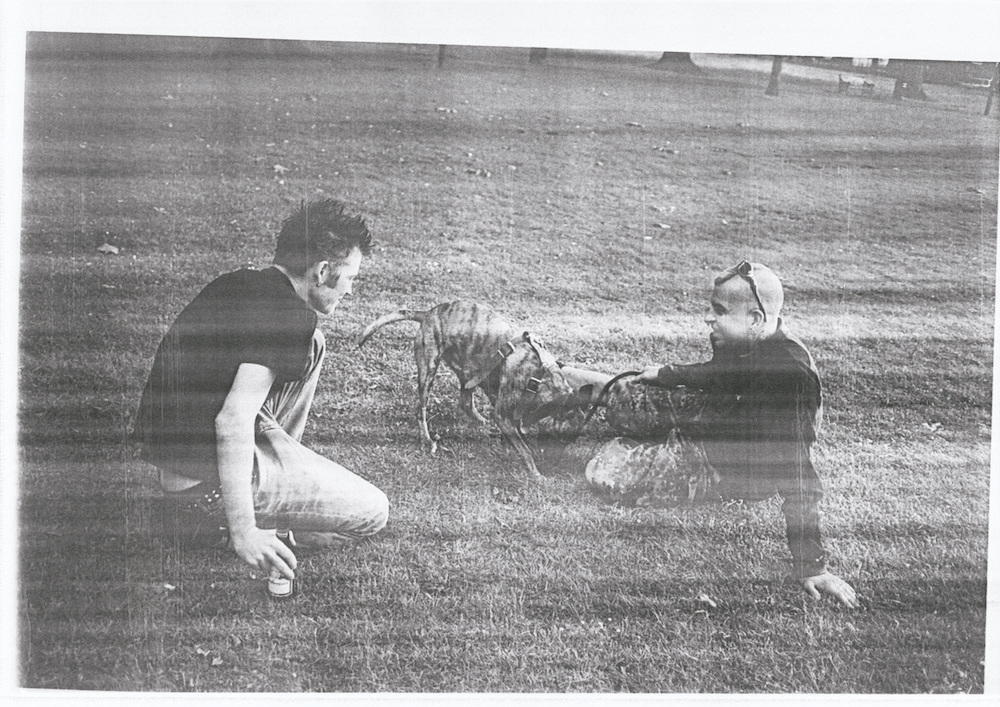

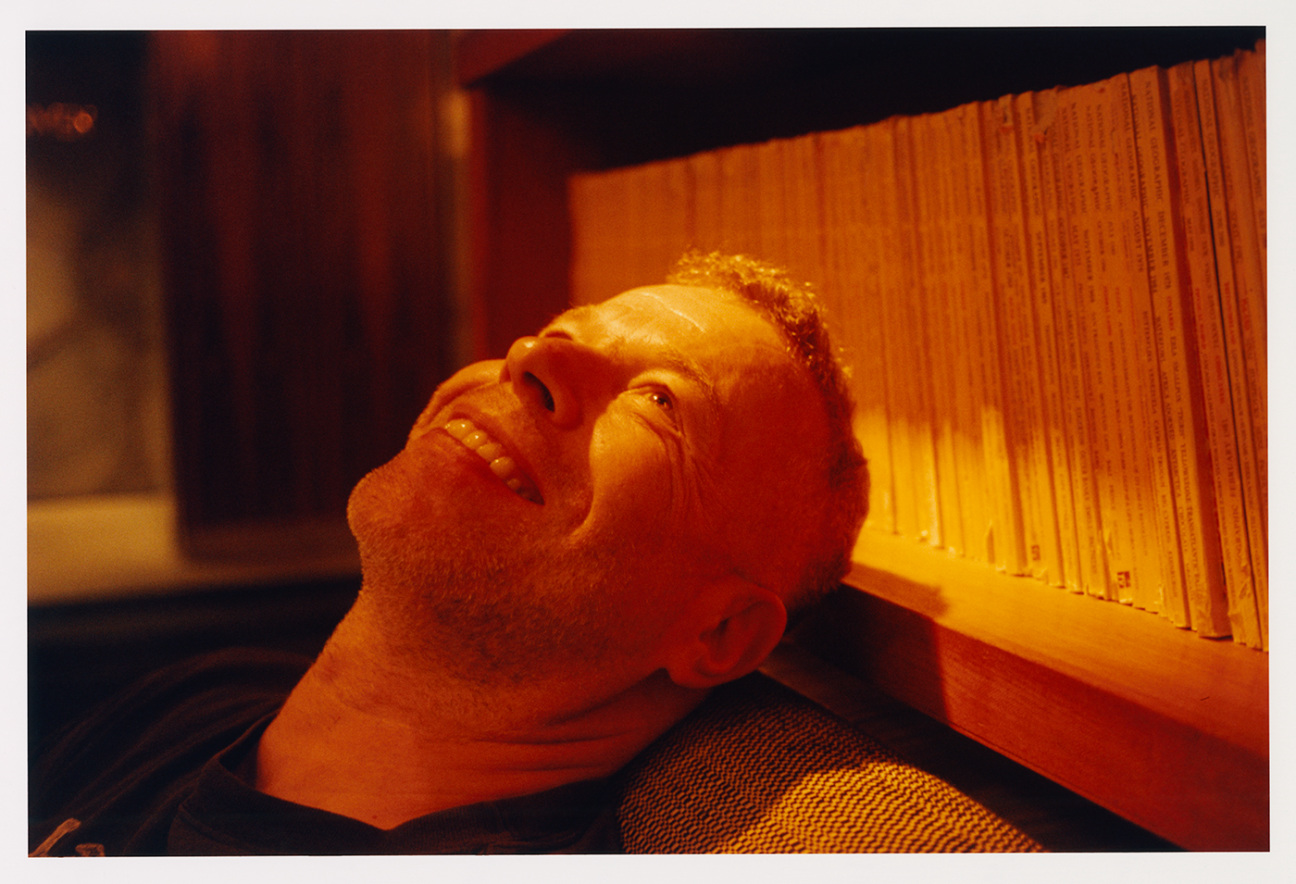

Ahead of his first U.S. retrospective Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear at the Museum of Modern Art, which covers more than three decades of work, including multimedia installations, videos, and of course, photographs, Tillmans meets up with fellow photographer—and his pen pal of the past two years—Adraint Khadafhi Bereal. Tillmans is known for transfiguring how photographs are displayed and consumed, hanging in unlikely places in a corner, above a doorframe, or beside a fire extinguisher. In the retrospective, which opens in New York today, his works are displayed in a loose chronology on the museum's sixth floor. The two artists, with similar sensitivities for the human condition and the in-between-ness of identity, talk about the ingredients that went into Tillmans’s massive show, their upbringings, the state of photography, and queerness’s infinite potential to bring us closer to one another and to ourselves.

ADRAINT KHADAFHI BEREAL: It’s nice to finally meet in person.

WOLFGANG TILLMANS: Reality is strange, but strangely real…in the way that a pen-friend is.

AKB: Do you think social media has brought us too close to one another that now we have instant contact with everybody in the world?

WT: It theoretically or practically has, but it’s not consistent. I’m shocked by how much people rely on electronic connectivity and how little people are scared of what happens if a device becomes blocked. We have to be aware that no human has more attention than 12, 16, and 18 hours a day. If we are constantly in that sphere, we are taking away attention from old-fashioned, researched, professional media. People on Twitter for an hour is an hour that they’re not having to read a well-written book. I want to stop contributing to that economy of time. We must insist that subscribing to a newspaper—or to a well-researched publication—and spending half an hour a day reading should be the norm.

AKB: My grandparents had all of these cassette tapes, DVDs. They were not hoarders but they liked to keep traditional media. I find myself buying all these magazines, books, and things that are physical that I can actually come back to and engage with. How important is the physical to your process?

WT: The photocopy has been the absolute bedrock of how I work. In the summer of ‘93—when I was 25—I started my first book. I made letter-sized color photocopies of every picture that I considered, then I laid them in sequence, front to front and back to back, so that you always picked up two leaves. That way you could always see a spread of pictures. It’s an important, haptic detail, because if you don’t grab the two sheets together, you see a white flash in between. You then hold yourself to a maximum volume, which creates a competition for inclusion, and then you can either throw out three pictures to kill three pages, you can reduce three, or you can reduce four and give a quarter page to each one so thatall four of them land on one page. Those are the editing questions.

AKB: The more technical details of how to cut down or maybe refine the post-process.

WT: It’s really just editing, any editor has to cut words. To us an article is complete, but it was always 60 or 420 words longer before we read it. When you’re an artist sequencing your own work, you think nothing is dispensable. But everything is indispensable, and to kill your own darling sis an art that you need to train yourself in—to learn, to let go, and to reduce.

AKB: Editing has been something I’ve been struggling with lately. We’re in that process with my new book, and finding the right things to fight for has been hard. Everything feels precious. It’s hard to divorce that emotional connection.

WT: It really is a philosophical question, not a technical one, and has been the nature of storytelling since day one. This need to edit and then to somehow find completeness is actually almost the art. Every era has its own technical restraints: how many words can you chisel into the stone, how many could you print without a computer, how many color separations you could get away.

AKB: How did your upbringing inform your practice?

WT: I’m grateful that my parents never held onto us too much. They always encouraged us to go away on vacations, learn languages, and be independent. Rhineland is a 20-million-person[area] without one metropolitan center, but it has a great history in photography. August Sander, do you know him? He wanted to portray society as it really was. Those cultural traditions that came before me are always part of my understanding without having necessarily studied them. It’s partially what has been actively fed to you, about what you actively sought out, and then there’s what comes with the milk.

AKB: With all the different leaps in technology and platforms since you start, I’m curious what’s in the milk of photography today?

WT: Photography is a really difficult medium compared to other art forms. I may be challenged for this, but I believe it is easier to make a sort of half-decent painting than to make a half-decent photograph that lasts. Maybe that is because it’s so easy to make a photograph that looks okay, or that even looks good. But to find an area where the technically presentable comes together with something that is intangible—that cannot be put into words; that makes it an extract of time or a slice of reality or fiction projected—is very difficult. I talk about it as if there is a threshold and as if there are criteria that you can fulfill until that result is then clearly visible. That is not how it works. There is no moment when it’s confirmed, these things mature over time after they’ve been released into the world. Photographs become complete through being looked at and being consumed and digested. That has strangely not changed even though we now have more pictures in the world than in 1995. Yes, everything has changed, but the rules are strangely still the same: really good photographs are extremely rare. They do still stand out, and I don’t mean a picture that goes viral. Today there is an enormous hunger for something new and anything good.

AKB: Instagram, for instance, changed so much when it started. What has been your relationship with it?

WT: I started in 2015, oblivious and not seeing any point in it. I initially only put typed letters and then, occasionally, photographs. I never assumed that anybody would think what I posted was my actual work. It hasn’t hurt me, but I realize that people take it much more seriously than I do. I must say, it’s overrated as a representation of the person.

AKB: You can’t know someone based on two posts. From a comparative standpoint, I try to stay off it. I see other 24-year-olds on Instagram that are on yachts, and buying cars, houses, and all these luxurious goods. It can put you in a state of delusion of what your life is supposed to look like.

WT: So let’s start an alternative. Does everybody have a dissatisfied, disillusioned relation to this, and we are still all captive of it?

AKB: We are.

WT: Then we have to change it.

AKB: I wanted to ask you about your retrospective. It’s the entire fifth floor of MoMA, right?

WT: The sixth floor. I don’t normally show in chronological order; I usually have an old and a new picture sit side by side to have a dialogue across decades. But I, along with the curators Roxana Marcoci and Phil Taylor, felt it made sense to lay out 35 years of my life in the 18,000square feet area right there. It was a very fruitful experience revisiting the works. My career started at the beginning of a 33-year period that one day might be described as the era between two Cold Wars. Now, there is a craziness in the world that was unimaginable 25 years ago. By their own vote and liking, there are countries that are following autocratic, heterosexist, heteronormative, and theocratic regimes. In Hungary, they happily re-elected their president [Viktor] Orbán, two months after Russia started invading their own neighbor. I’m not always talking about it in such clear political language, but the exhibition does show how my interests have not really changed. At the same time, I hope, there’s constant invention and new developments.

AKB: Will there be new works as well?

WT: It goes right up to 2022. I wanted to give roughly equal space to each of the last 30 years.

AKB: The first time I came across your work was in 2018 in an advanced photography course. I went to the library and pulled one of your books—I think it was green and self-titled. I was looking through, and it just opened up a whole new world. That was the first time it clicked for me, this is what photography can do. What I was learning before that was transactional; it made me feel like I was working in vain. It switched the gears.

WT: When somebody’s work really touches you, it’s important to seek them out, and a well-edited book is as much a mentor as a personal meeting or contact. I was touched by the work of Caravaggio in my own education. I couldn’t interview him, but in the late ‘90s I made an effort to see as many of his paintings around Europe as I could. Photography is a man-made language, which we are only fluent in because of the generations before us that formulated it. I find it terrible when I speak to students and I realize that they actually haven’t looked at other generations’ work.

AKB: Yes, because everything’s so digital now. We’re not in the darkroom with one another anymore, so it’s difficult trying to find appropriate spaces for those types of conversations. You started out at the height of the HIV/AIDSepidemic. The photography industry was booming at the time, but the media was very vicious about how it portrayed HIV. How did that shape your relationship with media today?

WT: I’m always super cautious when using the term “media,” because it is only valid to me as a single term when describing physical mediums. There were not only hostile media publications, of course; there were also intelligent and understanding outlets. But you were trying to go in another direction about queerness.

AKB: Yes, it’s something I have a connection with personally. When I started to redo my book, I felt like it unlocked a key for me in terms of understanding my own queerness and how I could express it—how it could exist out in the world. Sometimes there’s such a strong pull to identify or subscribe to something. I think I sometimes don’t want to have an answer available when talking about queerness because it’s gotten co-opted like everything else. I’m curious about how you observe queerness as a whole and what that means today.

WT: I’ve been traveling the African continent a lot in the last four years. There, queerness is still a matter of literal life in the closet or life in jail, and, to that end, LGBTQ rights still face a huge human rights issue on a global scale. But if we are speaking about, say, New York, Berlin, London, I personally find the term “queer” more interesting as an inclusive term and more meaningful than the minutiae of gender, self-affiliation, self-identification, pronouns, etcetera. Of course, everyone has the right to speak on those terms, but I find the term relevant when applied to all sexualities. For instance, are you somehow open-minded and playful with your body and your outlook on life? Or are you holding on to fear and the status quo? There are gay people that I wouldn’t call queer because they are very much formed and not interested in questioning their own ideas. And then there are heterosexual friends that I find totally queer, radically hilarious, and funny. I’ve always celebrated this tragicness and ridiculousness o fa life confined to bodies and the power of fun in dealing with it all.

"To look without fear" is on view at the Museum of Modern Art from September 12, 2022 to January 01, 2023 at 11 W 53rd St, New York, NY 10019.

in your life?

in your life?