How did you arrive at the title?

Campbell Addy: Initially, it was Feeling Seen with a question mark. It was going to be about how I’m trying to feel seen. Then, upon speaking to my friend Devin Morris, he was just like, ‘It’s not a question anymore, is it?’

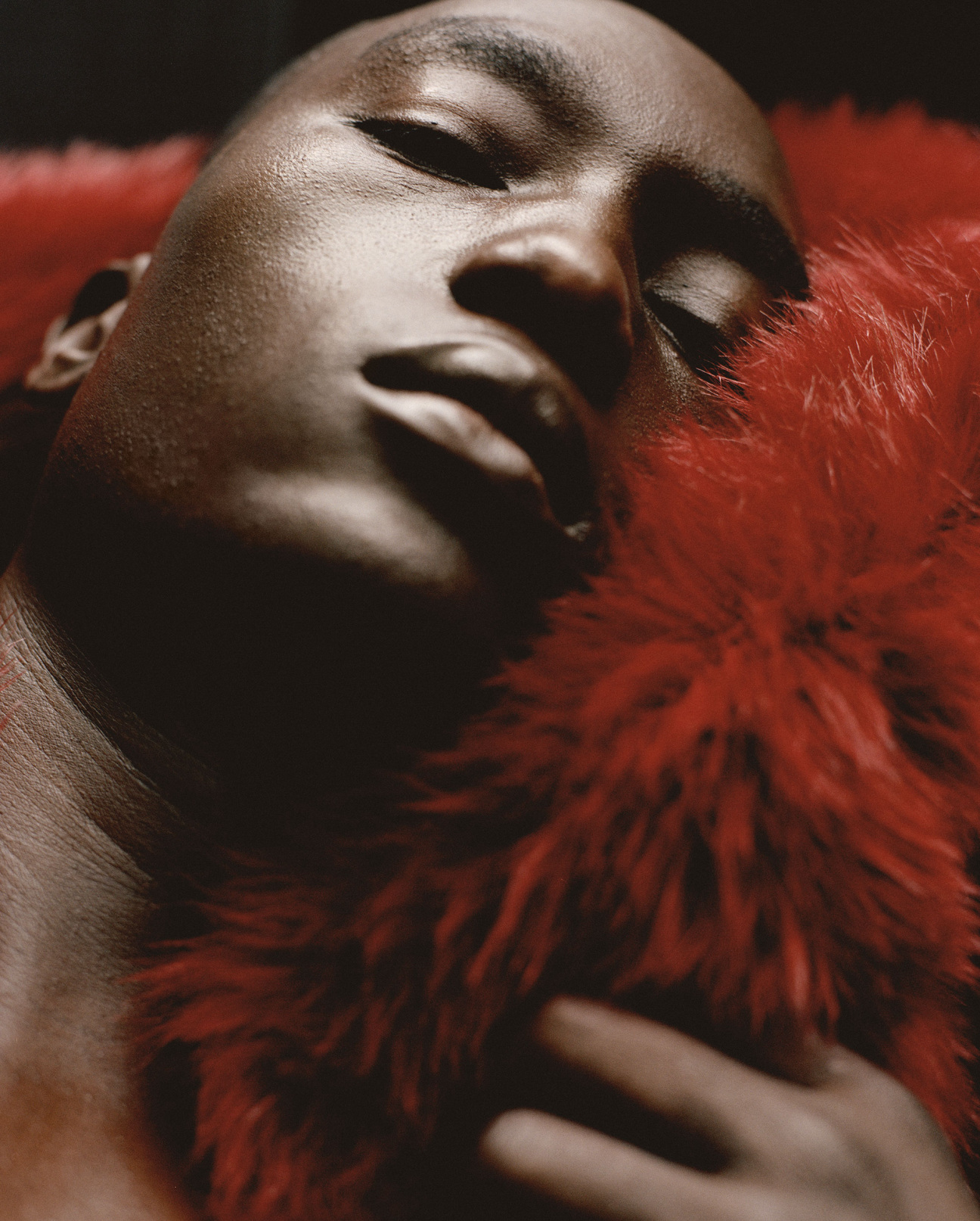

And what about the cover?

CA: Before we even designed the book, I came to realize that the cover had to be a Black woman because I am a product of a Black woman. As for the color—it’s weird. I find that when I’m working through emotional pieces or times in life, red is a constant. I thought this would be quite nice, for the beginning of my career, my first book to have red, Black women, “feeling seen.”

Red seems to be really powerful in this book.

CA: Every time I’ve had to look at my archive, it’s always the thing that jumps out at me. For me, red symbolizes passion, blood, death and romance. I’m an intensely emotional person, so I find subconsciously I’ve been attracted to little pathways of exploration through color. Sometimes it’s a soft red, and sometimes it’s deep and passionate. I don’t know if I’ll use red in the future, now that I’m so aware of it. The last six years have just been exploration, and you know, finding oneself and all that malarkey.

You have a fair few guest stars in your book: James Barnor, Naomi Campbell and Gabriella Karefa-Johnson. Why give so much space to others in your monograph?

CA: I juggle with this theory of consciousness. I have such an issue with time, and I love to link things: my existence here, the time, my work. What I do is not because I woke up one day and thought, ‘Yes, I’m going to work hard!’ Work ethic is very important, but I was raised by a village, literally. I come from a community that raised me, it wasn’t just a mother and a dad. It’s the same with my creative world. Every person I meet, it’s an exchange of information and passion, and so in my first book, I felt very odd having it be all about me. It would feel false especially with the words “feeling seen” on the cover.

It was imperative to have female voices in my book from different areas of the industry so that even if people look at my book and are unaware of the work I do, they can understand a little bit more into the psyches of the people rather than just see their work or their race. And then with James, it was purely emotional. I met James in the middle of the pandemic through Simon Frederick. I was literally there at my table praying to the gods, please send me a mentor, because I just felt lost at the beginning of the pandemic.

James told me he didn’t come to fruition until his 80s, and how he just wished he was 10 years older so he could enjoy it; it made me break down. If I was born 20 years earlier, I may not have a career. When I talk about James, some people are like, “Oh, who’s that?” It made me very sad. I want everyone to know that without people like him or Naomi, my existence wouldn’t be valid in the bigger scheme of things because James takes pictures to be seen as art.

How did you decide what images of his to include?

CA: I’ve tried to curate images of his that reflect some of how my work is being inspired. Like the Mohammad Ali image inspired the portraits that I shot of my brother in Ghana near where James grew up. We often don’t get to see Black history within the photography art space as being so linear. James and my timelines overlap, and I want to make sure that it’s solidified somewhere so that the next generation can understand that he did it for us and I’m doing it for them and so forth.

Do you see yourself as an archivist of joy? Are you your friends’ documentarian?

CA: It’s hard because, when I think of James, his images are integral for the history of Ghana and for Black people. When I think of my work, I feel like I’m a neo-documentary photographer. Because in the era in which I’ve grown up, everyone has access to documenting their lives. But the space I inhabit is one that not a lot of people can or will. So, with that space, I would like to document and shed light onto a type of people that will forever be known in history. Growing up, I wish there were more images like the ones found in my book and Antwaun Sargent’s book; it would make a lot of my insecurities go away. I probably would have started photography earlier.

In one of the interviews you talk through your timeline of photographic heroes. You start at Richard Avedon. In school, you find Tim Walker while you are simultaneously looking at Chris Ofili and Steve McQueen. A little later on, you uncover Deana Lawson and James Barnor, but your question is why did it take this long?

CA: I wasn’t someone who picked up a camera three years ago. I wasn’t in another industry; I was always a fine artist. I painted first and did photography at 16. I was at fashion university for four years, one of the best in the world. And there was such a lack of Black representation and after, when I discovered Black artists, most of them I found through my personal explorations or through a friend of a friend and that’s what makes me kind of messy. I’ve been sitting here really going to galleries but only seeing three photographers there. It doesn’t make sense and I’m still on a search. I would love to know for all the great fashion photographers from the 1970s, who were their Black counterparts? I know they existed. It was hard finding out all my favorite images of Black people weren’t made by Black people. And that’s what made me want to make my own images, because it’s different when it’s coming from within the community, as we can see now.

Is showing your work in more art spaces something you want to pursue?

CA: Yes. If we had to give it in percentages, my work is in magazines, say 60 to 70 percent of the time. I want that to change; I want my work to be seen in galleries and bigger spaces. And that’s mainly because of James. He asked if I’ve had any work exhibited. For the life of me, I couldn’t answer without insecurity. I said to him, “I don't think I’m good enough.” All that nonsense. And he just said, “You’ve got to do this; you’ve learned the business of it and you’re able to make money from it.” These are things a lot of his friends couldn’t do, because of the times, and we have that access and that knowledge to go out there and show the world.

Fashion magazines are great, but I have an issue with fleetingness. In the gallery setting, you come to a show and spend time looking at it, and it’s not just a swipe through on Instagram. That’s why I like books as well because it’s a steady progression. The goal is to have a solo show of work but also that work will be very different.

I see you as a Roe Ethridge or Deana Lawson type where sometimes the work comes into magazines, but it mostly lives in galleries, museums, institutional spaces and more permanent publications.

CA: I didn't think until I met James that someone said point blank to my face: “We want to see that.” And again, representation is key. If I had met someone like James when I was 16, I think my career would be very different because when someone who has done it looks at me and says I can do it, it changed something in my mind. I’d got the seal of approval now.

Are you paying it forward?

CA: It started a couple years ago with a mentorship program with the British Fashion Council. And then the last two years I’ve offered a consistent internship. I worked with one man who is an amazing Austrian-Nigerian photographer. Now I have an intern who’s an amazing photographer from Hong Kong. The main thing I try to teach is the business because it's all these little skills that matter.

Like email etiquette. It’s designed to keep out those not already within the system.

CA: When I first started shooting, it was so daunting. None of us had anyone older to ask questions of. So yes, I’m very much open to having mentees; the only rule is you must love it more than I do. If you love it more than I do, then you’re going to be fine. I wish more of us were mentors because there are so many young people. The next generation would be 10 times better than us.

One of the things that I found kind of touching, verging on self-sabotaging, is that you included this poem that you wrote when you were 19. Why you would risk detracting from your picture making?

CA: When I created the book, I wanted it to be like a journey. I thought of the name and then worked on the sections. I knew I wanted to include seen and unseen images from my past. And when I was going through my journals—I haven’t gone through them in years—I remembered that poem. I had sat on it for ages. I’m not a writer at all, and I had literally finished writing it a couple weeks before I was admitted into a psych ward. It was at a point in my life where I was just very tired.

I like to connect dots in my life almost to my own detriment. I thought it was important to put the poem in because despite the great things that I’ve been able to do, I’m still human, and we’re all still human. Amongst all this joy there are still some dark spaces.

Well, I was impressed by the writing but also because so many of the images in the book are so joyful and portray Black life in a much different way than we see it generally.

CA: I make a conscious decision not to create trauma porn. When George Floyd happened, Azealia Banks wrote a post asking why we were sharing and resharing trauma that only affects us. I thought, ‘Damn.’ I couldn’t unsee it. Of course, I believe history should always be taught honestly. Words and songs are great vehicles, but I don’t think my work could ever be because of its immediacy. Unless it was a movie or a short, I don’t think my work could be that dark.

In one of the texts, you speak about 2019 as a turning point for you. Can you tell me what were the events leading up to that?

CA: By 2019, my peers and friends were also doing fab things, it was almost like wow look at us all. We all floated to the top and it was great but in that same breath I was like, “Oh, I really hate this feeling of being visible” because once you create work and put it out there, I didn’t realize how much hate there is out there. I wasn't pushing for fame; I was pushing to create work and have my ideas be heard, I didn’t think of the other side of it: people picking it apart.

Now, I’m retreating a bit more. I’m trying to be slower with my process. I resolved that I do not need to fight for this machine or industry, as people like to call it. I’m a bit too sensitive for that.

Did finishing this book make you want to start another one immediately?

CA: I already have an idea and that’s the annoying thing: I think the next book will be 100 percent new work. Maybe over 10 years in three intervals. I have a fascination with time, and I would love to revisit a subject again and again.

Do you know the work of Tehching Hsieh? He did all these one-year projects. He’s an artist that’s really played with time on its terms: endurance.

CA: Please send me the work! You know it's funny, but I have a huge issue with how quick things are but then also I’m so impatient. I’m wondering if I started a project now, by the time I’m 30 what would it look like? That’s kind of where my mind is. In the pandemic, I took a picture every day. I look at those pictures and I realize you start creating a language that you don’t even understand. I’m trying to build something that isn’t so fast. Who knows? My next book might be called, Time.

It’s the luxury of the future.

CA: I’m 29, and today I went for a walk. It baffles me. I didn’t have that time even six years ago. To walk around for an hour and leave your phone at home, I feel like a millionaire. I need that to now be translated into work, but we’ll see how that changes.

in your life?

in your life?