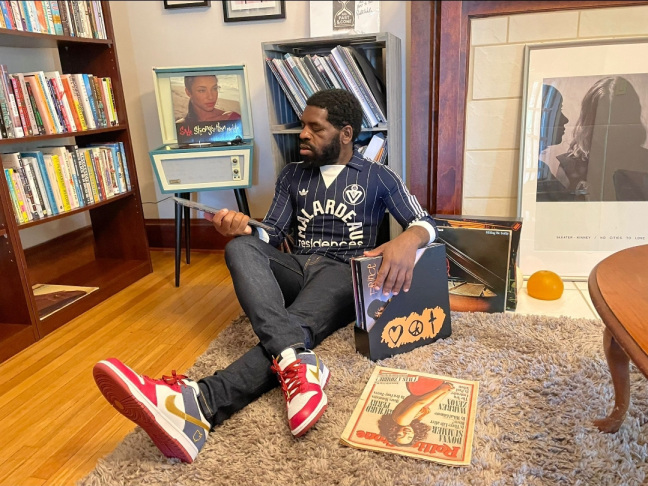

When Hanif Abdurraqib was 16, his idea of success meant finally being able to buy a car so he could cruise around his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. The last 12 months, however, have brought him more success than he could have imagined. The essayist, poet and critic has had a banner year of praise and recognition, featuring everything from receiving a MacArthur "genius grant" to being named finalist for the National Book Award. The world has its eyes on the glory of Hanif. In January, when Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) tapped Hanif to be Guest Curator-at-Large, he received yet another celebrated stage on which his visionary work could unfold.

Rachel Elizabeth Cargle: It’s said that you are bringing together “genre-defying music” in this curation. What makes a piece of music or an artist defy genre?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Bartees Strange was such a great example of this because he is someone who pulls from a lot of these elements. I mean, he's an artist who, to my ear, is as interested in the Black roots of American folk music as he is in just noise. Little Simz is someone who I think is so efficient as a writer because she understands sound, and prioritizes sound in a way that stretches beyond whatever genre box someone may put her in. She is, to me, a griot. She’s just as much someone who delivers the news via song as she is a rapper.

REC: BAM announced that this would be a series of “artists as storytellers.” The selected performers span age, genre and style. What was the throughline of this series? What story was happening in your head as you were curating this lineup?

HA: I'm glad you mentioned age because it was important. This was such a multi-generational experience and experiment for me. Speaking to my comment about Little Simz as a real storyteller, there was an urgency to pair her with someone like Nikki Giovanni. I leaned into storytelling and narrative because I wanted people to step into a show and feel like they were stepping into an “elsewhere.” Any kind of elsewhere, not even one that is necessarily better than the here, but an elsewhere. Live music can offer an alternate reality, it doesn't need to exactly supersede our present. But just the option of an alternative, I think, is generous.

REC: If you were to have done this curation before the coronavirus lockdowns, I'm guessing it might have looked different from what we see today. I want to know what aspects of this project were influenced by having just lived through a global pandemic.

HA: I am a much more patient curator now. If I had done this before the pandemic, I don't think I would have gone into it with a guiding principle of: “How can I make not a show, but an experience? How can I make this worth everyone's time, particularly my own?” It was a selfish act, right? Of course it appears selfless because so many people get to interact with the curation, but it was, in part, a selfish act of me saying, “What is going to excite me enough to get me out of the house?” And it takes the miraculous—it takes Nikki Giovanni being up for doing this kind of thing. It takes Dev Hynes being like, “I'm gonna craft an entire orchestra,” you know, these kinds of things.

REC: What is that thin line between a show and an experience?

HA: I can tell the difference between a show that people loved and an experience that people were immersed in by how speechless they are when they exit a place. I got to stand outside of BAM after the show featuring Mdou Moctar with Bartees Strange. As people exited they were kind of just looking at each other not saying anything, you know, language wasn't coming as easy. That was really magical to me, to kind of covertly watch people come out of the door. Language has to climb the mountain of what we witnessed. It'll get there, but in the immediate aftermath, if it's not there yet, that's a real gift.

REC: What is it you want the audience to take from witnessing these shows?

HA: I hope you walk away from them not with the story that I tried to pull together, but instead with a story that you were able to pull together through witnessing. A story about rebirth and rejuvenation on your own terms, and being present again on your own terms. I think the last show is like mid-to-late May, which is intentional because I wanted to end before the summer. My hope was that this could emotionally catapult me into summer. You know, summer is for me the highest season of possibility. So I would love it if anyone who exits this series of shows can simply leave feeling a newfound relationship with the abundance of possibility that rests beyond the stage and beyond the venue and beyond the show itself.

Rachel: If you were to have been given this opportunity in the 1990s, who do you think would have been part of this curation?

HA: I would have, like, Sounds of Blackness open up for Groove Theory. I would have Digable Planets and Bahamadia on a bill. I would have FanMail-era TLC. Or, like, I would try to build an entire show around that collective of musicians. Aaliyah, Missy, Ginuwine, Timbaland. If I could get all of them at the height of their powers, you know? I think giving Missy access to a stage that looks like the BAM Opera House to do whatever she wants would be thrilling to see.

in your life?

in your life?