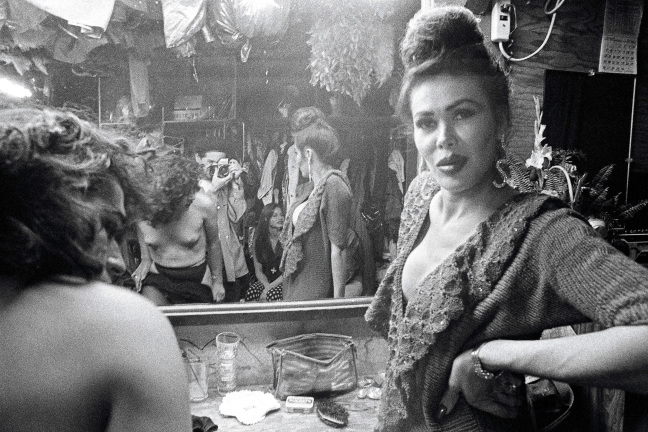

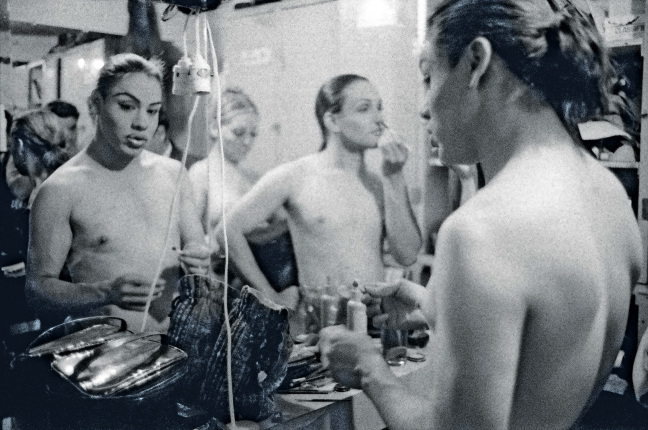

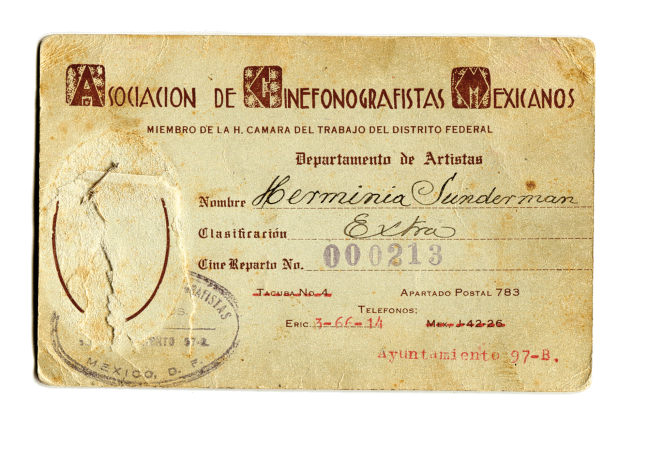

Reynaldo Rivera connects ideas across eras, referencing local histories, silent movies, Mexican divas, writers and politicians. His father fervent in his desire to have un hijo de la patria, Rivera was born in Mexicali, Mexico. He grew up traveling itinerantly up and down the coast among various towns in Mexico and California. He initially used photography as a tool for stilling time, his early photos focusing indiscriminately on his surroundings, but he became more intentional as he grew older, perfecting his craft. He took pictures of places he went and the wide range of people who surrounded him: first the cleaners in the pensioner hotel where he lived with his father; then his family; street vendors and street corners, and, later, fake fashion shoots for LA Weekly, candid interactions between friends, music shows, house parties and on stage and backstage in queer clubs where trans women and drag entertainers performed.

These images comprise intimate moments of preparation and dazzling outbursts of glamour in public. They’re a gathering of evidence he leverages later in this conversation to litigate his photographs: the way they function as fact and fiction alike, as proof and product of his cohort’s imprint on the city of LA and an antidote to the distinctly American amnesia that keeps decentering the Latina/o narrative.

His body of work from the 1980s and 1990s, rarely seen until recently, is full of moments that would otherwise be committed to memory— fleeting light and figures that level recognizable names such as Sonic Youth, Los Elegantes and Jean Baudrillard with fresh and lesser-known (yet no less glamourous) faces. In his dark, cinematic images, Rivera focuses on “how his subjects want to be seen,” to quote Chris Kraus, or the slippage between self-perception and appearance that happens between a face and a mirror—or a shutter. He specializes in simultaneously capturing both their interiority and their outer shell through his skill for mining intimacy from his subjects and refracting it onto the surrounding context. Rivera recently produced a monograph published by the beloved literary, philosophy and art press Semiotext(e)—co-edited by Hedi El Kholti (and myself)—and he was showcased in the recent Los Angeles biennial “Made in L.A. 2020” (curated by Myriam Ben Salah, Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi and me) at the Hammer Museum and The Huntington. In his book, Rivera’s friend, the aforementioned Kraus, delivers a searingly precise account of his unruly early life—likely the result of many conversations—that traces the roads that led him to now live in a towering Victorian house in Lincoln Heights where a pristine record player, cared for with tenderness, spills obscure Russian vocalists, Lucha Reyes or Nina Hagen onto the sidewalk shared with a bustling body shop. We recorded this conversation in two bursts in September 2021.

This text moves from old traditions to Rivera’s newest work, which is still in progress, and nods to the people and scenes that have shaped him. It also highlights his fierce distaste for the powers that enforce the ephemeral nature of a scene that was not only deeply influential on him but also one he views as foundational to the LA we live in today. These works were never driven by an archival impulse (neither the preservation of his own work nor a particularly documentary-like mindset). They hold contradictions and poetic fallacies, an intimate and instinctive excavation of a city and the people who fill it.

LAUREN MACKLER: So, over the past few years we have spent a lot of time together, we’ve had a lot of conversations about your work, and we wanted to start this one with the relationship between oral traditions and photography.

REYNALDO RIVERA: The language of imagery.

LM: Also, the role gossip plays in this kind of storytelling: the hearsay, the aggrandizement of self-perception…

RR: Great art is gossip.

LM: Ha, yes.

RR: Okay, I’ll act like it’s fresh: As a child in my village, I would sit around and listen to all the old farts talk in the kitchen at the big events, the Christmases, the birthdays, the deaths. They would sit around and talk about all the big feats of the town, and it was their way of remembering these things. They were passing this info to the younger folk.

LM: An expanded family history.

RR: It’s like verbal imagery. I used to love hearing all the stories of the great-greatgrandfather that got conned by los Cristeros or my great-grandmother whogot raped by… what was his fucking name? Leon Pena. Maybe Leon made her suck his dick. They would get graphic sometimes. This is during the Mexican Revolution, like 1910. She lost all her lands, etcetera… People who don’t have other tools relied on this kind of oral remembrance. When I got older, when I discovered photography, I did the same thing through my images. It was image gossip. It was a way of leaving the stories of people that come and go. This is what my family or these older folk would do in my village. They would tell these stories of people that came and went. It kept them alive. Each family seems to have the designated receptacle of info, and later I became that person by default because no one else was interested and I did this with photography. Even though having a camera was never intended for someone like me; it was such a foreign idea for someone like myself that grew up in poverty or as a migrant worker. The first photos I took I just did to preserve these moments for myself. As I got older, I started choosing the people I wanted to include in my narrative.

LM: While it wasn’t your intent, your images are often read as documentary, and they function that way too, but you refer to them as fictions. Oral histories also have that relationship between fact and fiction because they rely on self-presentation and memory, namely the way memory fictionalizes fact—and vice versa.

RR: It’s storytelling, and you want to make the story captivating to keep the younger people interested. In a way that’s what the elder people did when I was a child, they told the story with their own flair. Also you want to make it interesting enough for someone else to retain this memory and retell the story because that’s how those things work. Like how Mexico had corridos—music that was created to tell stories as a way of passing information throughout a country—I describe my stuff as a visual corrido because I’ve documented people that in most cases are not documented, and events that go unnoticed, because usually in the West—the non-oral-tradition folk—they always just want to capture the big events. I’m a sucker for the ones that go unnoticed. When I read about the twenties, the thirties, I always wanted to know what regular folk did. Because you always read about the movie stars, or that guy that crossed the Atlantic, or whatever, yet you never really get a feel for what things were really like.

LM: Also it matters that it’s through your lens.

RR: Everything goes through someone’s lens. Like all those performers in my work, to me, they. were like Garbo and Dietrich and these other gals that I fell in love with as a child watching movies. When I started documenting the performers at Mugy’s and La Plaza, to me they were larger than life. I wanted to document them in this way to give them that. And that’s why I wanted the pictures at the Hammer to be that big, because I wanted people to have to stand back to see the whole image and it’s like, “Don’t get close, bitches”—they are stars. What I find rewarding now is to be able to see these performers at LACMA and all these other museums that have bought the work. Now all these gals are going to be seen. Unfortunately, in their own time, they were throwaways. They were the people that no one gave a fuck about, that someone would throw over a bridge in a suitcase. Unfortunately, that’s how so many trans folk end up now, it’s still part of our current history. Through my lens, and not just my mental one, I’ve immortalized these girls.

LM: Today, we were in conversation with an institution that is considering the acquisition of your archive. It was striking to realize that all the information pertaining to these images [currently negatives in plastic sleeves and stacks of prints]— dates, names, places—lives in your mind, that’s all in your brain—nobody else can really caption them. Some other people may be able to corroborate the information, but you’re a kind of “keeper.”

RR: It’s my story. I am the orator—is that the word?

LM: Yes.

RR: These are all the characters in my story. Stars in my movie. The same way that these older folk in my village chose the people they remembered. They decided who was worthy of being remembered through what they felt was valuable to the family. People remember things for a reason, and everyone chooses. We are constantly curating our life. I’ve done this through photography. By the time I shot all these performers, it was a conscious decision to document them for posterity because, by this point, I was seeing things differently. It was no longer just saving shit for myself. And there was a reason I shot all this video alongside the pictures, because I was thinking, someone is going to wonder what this looked like moving, and I thought so many of these things are so fucking amazing that it made me want to also document it that way.

LM: I’m glad you brought them up. Your videos are so captivating. Handheld and often shot through mirrors (like the pictures), they straddle the line between the spontaneous and the choreographed. In the cut you screened at the Hammer as part of “Made in L.A. 2020,” you show seemingly casual nights out, days browsing the flea markets, windy car rides shot from the passenger seat, house parties and then multiple takes of a single scene in a bar bathroom. That last shot plants a seed that everything here is a little rehearsed or staged. There’s also this moment where you interview someone in the bathroom through a mirror. You are in the frame, asking him about sex, teasing out his story, edging his desire. You interviewed a lot of people in the videos in this unique way, kind of egging them on. What are you coaxing?

RR: Again, I’m curating. I wanted something. In most cases, people see you differently than you see yourself. Obviously, to me, a lot of these performers are larger than life, and so I wanted to pull that out of them because these folks only sell themselves in that limelight while they were on stage.

LM: And that’s really fleeting. There’s more.

RR: Yes.

LM: In a public conversation you did for Artforum last year, I remember someone asking you about glamour, and you suggested that behind the glamour, there was a lot of violence. Sometimes, in person, when you recount the stories of some of these performers, you reference tragedy and horror, but the viewer might not see that in the pictures.

RR: The reason I don’t dwell on those things in the pictures is because I don’t want another tragic story about these people. I would rather concentrate on their output, that what they were doing was amazing, and that they deserve to be seen or remembered for other things than their tragedy. They had full lives. And the thing about the glamour is that glamour is violent. Well, it’s just because glamour is a façade, but what does it take to get that façade, to get that steely look? All these girls went through a lot of shit to get to where they were, to get that look. It didn’t come easily. Their bodies cost them a lot and, in some cases, it cost them their lives.

LM: There’s an element of artifice throughout your whole body of work, even when the images are—contradictorily—somewhat candid. Even in the house party scenes you draw a performance out of your subjects.

RR: The photos look the way they look because, again, in that case, it was really knowing the right moment to take the image. There were 50 crappy photos for one amazing photo. You’re waiting for that moment. That comes from just doing what you do for years, just knowing what looks good in that little square. It’s like learning to view the world through a specific thing. I noticed that people, that photographers and cinema people view the world through their medium.

LM: Just constantly framing.

RR: Yes, I think we do. It’s just something that happens naturally after years of doing this shit and because it’s not as easy as people think to get something on film the way you see it in your mind. Most people take a photo and go like, “This is not the way I saw this image.” It’s not easy to actually get what you wanted.

LM: For me, being in front of your lens for the first time was really pivotal in understanding your work. The way you banter. Of course, everyone’s different, so it’s probably a little different with each subject.

RR: Right. You have to play a different tune to every person.

LM: My experience was that you really don’t fawn over people.

RR: No.

LM: You’re much more like, “Stop doing that.” You shut down a thing to get another thing. What are you shutting down?

RR: That either works or it doesn’t. People that are very sensitive tend to get crushed. I have a big thing about honesty. Because at the end of the day, I want to get a good photo because I want to make you the best I can, make you whatever I think looks good.

LM: Are you trying to make people look good?

RR: Yes, of course. That is the bane of my existence. To me, a big nose is amazing, but everyone has their weird things about their face. They hate their nose or they hate their eyebrows, their eyes. Usually everyone is always waiting for the right moment when they lose enough weight, and that moment never comes. You’re always seeing yourself through that fucking weird prism of your brain, which is always telling you you’re not good enough or you’re not whatever enough. That’s been my experience with most sitters.

LM: Actually, it relates to how the mirror is such a big player in your work. You’re often shooting people looking at themselves or looking at their reflection.

RR: Mirrors are the ways people want to see themselves, and I’m all about their fantasy, not their reality. Actually, there’s this one image of this one guy who usually didn’t do shows—one of the girls had not shown up so they slapped this dude in a dress and a fucking wig. It was really awkward.

LM: I remember that one.

RR: I love that image of him looking in the mirror because I almost feel like the reflection that’s looking back at him is so different from the person he believes himself to be. He’s so unsure of himself looking in this mirror. That’s one of the images that I like the most, but it’s probably because I know the backstory. He had never done this before. You could see it in his body language in this tacky dress, in this totally bad wig. It looks like it’s backwards. Oh, my God. I really love it.

LM: One time when I asked you about the mirror in your compositions and your reflection in it, you explained that it is also a portrait of you.

RR: Is that what I said?

LM: As much a portrait of you as it is a portrait of others.

RR: Right. Oh, yes. A lot of times I wanted to be part of the photo. Well, there were times that I’m in the image because when you’re looking at it, you’re not just seeing it through my eyes. It feels inclusive. It’s not like Arbus’s images where you feel excluded immediately. I don’t know if you’ve noticed that her photos really feel exclusive. There’s this hand that is not letting you get close to the sitter. I think that comes from her. She was not close to anybody. She made normal people look freaky. I think because through her lens, she viewed the world as a fucking alien experience. She couldn’t get close to anything. I’m not this way. The reason I bring her up is because when I was younger, people used to make these connections to her all the time. I could never figure that shit out, because I felt that the only similarity was the subject matter. I always felt that the feel of our work was so different. Everyone that has talked about seeing my work always has said that they feel like they’re there. I think it’s because I was there. When I took the photo, I wasn’t just there with my camera. I was part of what was happening, which in a way makes you feel included. I didn’t make people that ordinarily society would have deemed as freaky look unfreaky. I usually made them look good. I’m still doing that, except now, I do it much more singularly. My old photos are very busy, there’s a ton of stuff going on everywhere, which was what I was about at that time. Now I’m about individual things. Portraiture.

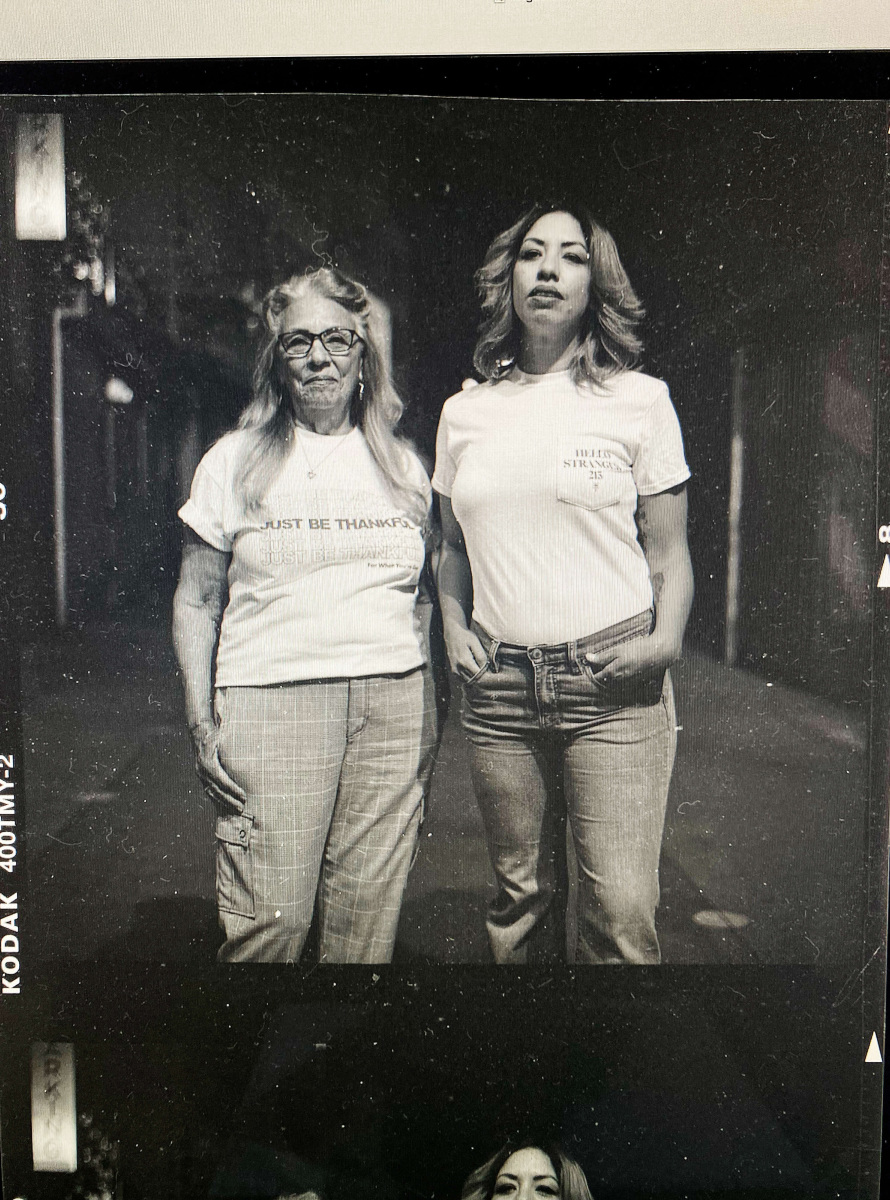

LM: Who are you shooting now?

RR: I realized I am mostly shooting transplants, people who are new to this city. The portraits are as much about them as they are about the city around them as it changes.

LM: You tend to shoot people who are close to you—sometimes newly close, sometimes long-time and trusted. We should talk about family too.

RR: Right. One thing that gay folk, in general, have to experience early on is the making of our own families. Luckily, I was close to my immediate family, but I was as close to them maybe as some of these other friends that I’ve collected that became like family throughout the years. The recent book in a way is a family album in this whole tradition of preserving the people that matter to you. You are everyone you’ve ever met. You’re a receptacle. If you really are honest with yourself and look deep, you’ll see how every mannerism, every fucking thing that is you, you learned from someone else or from an exterior influence. This is the kind of shit you think about when you’re old. You start connecting dots.

LM: I think it says something about you too, that you let yourself be imprinted.

RR: We all do though. I just think some of us are more honest than others.

LM: I also think your images, your aesthetic, seem to live across time and eras. Through the notion you mentioned earlier about people being “mosaic-ed” inside of you—but also the images you’ve spent time contemplating: family pictures, your neighborhood’s history, silent films and the Golden Age of cinema, album covers…

RR: The more you’re exposed to shit, the more your brain has to borrow from, and it makes for a much more interesting image. We all borrow from everything. People you’re around for a long time, have you ever found yourself mimicking shit they do? You start becoming very similar and then that stuff stays with you when they disappear and it becomes part of who you are. It happens so subtly. I was telling the curator from the Getty earlier how little documentation we have—by we, I mean Latinos. It’s where I feel the importance of this work really is now, that I’m leaving a body of work there for other people to remember that we’re part of these things, because that’s what connects people from different times and makes you feel like you belong in a place. Documenting the mundane shit makes you feel like you were here. In the US, we are constantly being moved from places. Look at Echo Park: look at how quickly we were erased from this fucking neighborhood. I’m not putting the blame on anyone. I’m just saying that this has happened to us repeatedly and this is why we tend to not have a sense of ownership. If you wanted to know about Latinos who lived in Echo Park, go fucking look for anything. It wasn’t out there, and I really feel that the book we made and this work is a testament that we were here. [In the book] we say, “This is Echo Park,” “This is Silver Lake,” and I did that on purpose to let other people know we were part of that neighborhood and part of what was going on, and we were as much trendsetters as we were following trends. We have always been part of this American experience, and we always seem to be put in the footnotes.

LM: Do you feel like that is changing now? Your work is becoming a reference.

RR: What is happening now is all of a sudden all these white folks seem to be so interested in giving us our own table, but again they are missing the mark, we don’t want our own table, that’s never what I meant. I wanted to be included in the discussion because we are doing all these things that are a part of what they are doing, what we are all doing. We have always been a part of the history of this fucking city. I wanted to let people know we never went anywhere. I did a workshop with young kids in the nineties in Echo Park, and one of the things at the end I had asked them was to write a little something about their neighborhood, and all the kids wrote, “This used to be a Jewish neighborhood,” “This used to be an Italian neighborhood,” this used to be every other ethnic group’s neighborhood. Not one said, “This has always been a Latino neighborhood,” yet the one thing Los Angeles has always been is a Latino city, because we were here before nearly everyone. Then this one kid wrote, “Art is something white people do,” and it’s so funny because I felt like this kid in that one sentence said what we all always felt. Just the fact that I picked up that fucking camera and did something with it is monumental because I grew up believing that that’s something we don’t do.

LM: There was no road map and it felt so improbable.

RR: There was no background in art. No education. Everything told me not to do it. That’s the magical part of all this—I did it anyway.

LM: I’m going to ask you one last question, about light as it relates to your newest work. When you shoot, you adamantly only use “natural light.” What qualifies as natural light in this city for you?

RR: Every city has its own light and its own feel. And it’s the person that is from the city that feels the change. I have really felt this change in how the city looks.

LM: It’s particularly related to lighting?

RR: Yes, well, the lighting part is related to all the suburbanites moving into the city who have brought with them that need for safety and security—shit that we didn’t grow up with and didn’t expect from the city. We wanted the freedom the city gave us and the anonymity that the city gave us in its darkness. The night in Los Angeles was magical, you felt this darkness, this penumbra, this in-between world, the shadows spoke. I think that’s why this was the capital of film noir, why it began here. And I really believe that by adding all this safety, all this excess light… you know everything is so well lit now. They just added two extra lights in the alley where I am shooting now. In a way, I am documenting the end of that space because every time I go back there, there is more and more light.

LM: “Well-lit” as in over-lit.

RR: Yes, safety-lit. They got rid of all the shadows.

in your life?

in your life?