Artist Jammie Holmes contradicts polite society’s devaluation of growing up in the middle of “nowhere” around “nothing”—urban misnomers that patronizingly describe America’s rural outskirts. The former oil-rig worker has enraptured art collectors and museums alike with large-scale figurative paintings about growing up, living, and working in Thibodaux, Louisiana (population: 14,567). And antithetical to the sea of Yale MFAs that pervades the art market, had he not grown up in nowhere around nothing, he contends he’d have nothing to paint. “Everything that I paint comes from experience, from something that I've felt, and I feel strongly about a lot of different things. I have 30 some years of built-up shit that I want to get off my chest,” he says.

At 32 years old, Holmes entered his first art museum to see a KAWS exhibition where he says, “I just thought to myself ‘I could do this shit’”—a notion he relayed to KAWS once they later crossed paths (Kaws laughed.) Ironically, Holmes wasn’t necessarily off base.

After his initial visit, Holmes upped his museum attendance, eventually noticing the conspicuous absence of nothing’s artistic representation. So, he decided to quit his job, reignite his childhood enthusiasm for painting, take the unadvertised road out of nowhere and bring an overlooked visual culture of 3.68 million rural Black Americans onto the main stage. Now, just five years later, he’s an art-world darling preparing for his first international show in Korea and celebrating his recent representation by powerhouse Marianne Boesky Gallery in New York City and by Library Street Collective in Detroit.

Despite a punctured canvas or two, Holmes’s self-teaching helped him produce antiderivative work in a market flooded by figuration. And, without a historical model to reproduce, Holmes’s work has enticed tastemakers such as Lenny Kravitz, who seek authentic artists putting out original work.

Still, the art world loves a comparison; just don’t expect Holmes to dig into it with you. He’ll give you a cool smile and a slight head nod, but such conversation is not his vibe. He laughs, “How am I supposed to be an artist if I'm looking to other artists? That is not my job. That is for collectors. That is for galleries. That's what museum curators actually know. For artists, it's not my job to know them. I learned them as I went.” However, he does give a special shoutout to his recent fascination with Caravaggio.

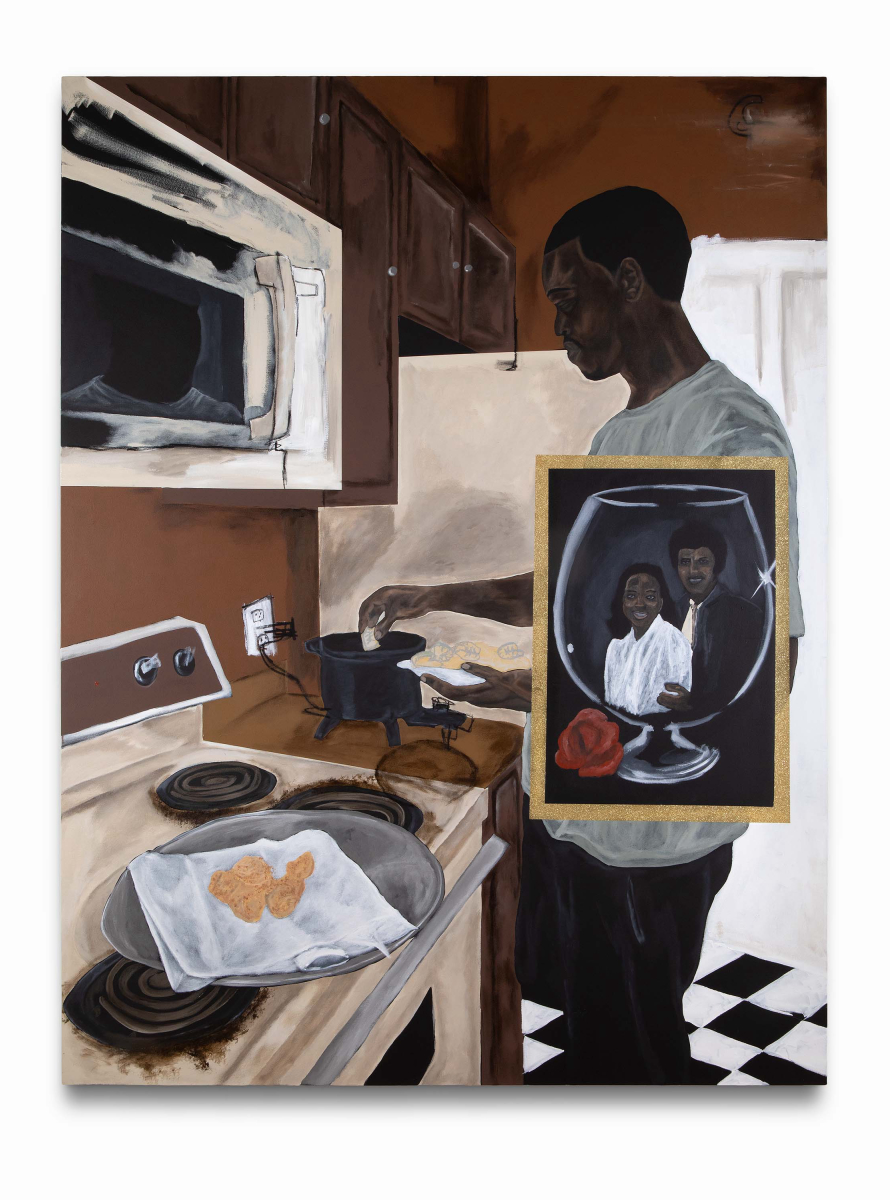

His newest show, “What Happened to the Soul Food,” curated by Matt Black, and opening January 27 at Gana Art Gallery in Korea, highlights Holmes’s continuous self-improvement with massive showstopper paintings like Glass House (2021) and Soul Food (2021), leaving space for the Korean public to “lean into the experience,” he explains. Though he recognizes that his international audience may not be familiar with the scenes of Thibodaux, he hopes “they can peek over the shoulder of [his subjects],” join in on the settings and pour themselves “a cup full of whatever.”

in your life?

in your life?