Art historian and writer William J. Simmons returns to his examination of queer-feminist art with Queer Formalism: The Return, a book sequel to his 2013 essay, “Notes on Queer Formalism.” The text fuses high- and lowbrow subjects, exploring the unexpected (but logical) communion of storied artists like Gustave Caillebotte and Diego Velázquez and contemporary pop culture symbols like Britney Spears and Harmony Korine’s 2021 film Spring Breakers.

The book is infused with the beating heart of Simmons’s own personal history: alongside shrewd academic critique lie diary-like confessions of heartbreak and childhood memories. There is a sense that he is writing for himself just as much as he is writing for the academic gaze. Excerpted in part below, the book’s introduction, which is dedicated to Twin Peaks character Audrey Horne, exemplifies this sentiment, evident in Simmons’s choice of references and his capacity to connect his lived experience as a gay man and as a scholar. And similarly, the Queer Formalism author responded to my queries on his latest work, the #FreeBritney movement and the process of art curation with kind, thoughtful introspection.

“[…] so often when we are young we do not give ourselves a break. This happens frequently with queer people, who feel the need to prove their worth to the world, who doubt their own inherent worth even as they affirm it in everyone else. Seven years later, however, I am only just beginning to see that perennially chasing a broken heart, living with a broken heart, did not make me or my “Notes on Queer Formalism” or any other writing projects better or more meaningful. I have since learned that being queer does not have to mean being sad.

“Yet this is the conceit of academia and art schools— that the only thing worth doing is suffering through bureaucracies and exclusionary tests in order to merely reach the next nebulous hoop that must be traversed, so that someday—some unidentifiable day—one might, if one manages to continue to pay the rent on a ludicrously low salary, have a legacy. And the only way to reach that legacy is through the paranoid language of critique; that is, we must find the heretofore unconsidered dissertation or artistic practice, even as we are meant to deconstruct notions of originality. Queerness, itself unconcerned with futurity in some iterations, as in the work of queer pessimists like Lee Edelman or the queer tendency toward youthful and pleasurable self-destruction, might be the answer to this double bind, for in queerness or queer formalism we might understand and find liberation in the facts that everything has been done before and that there is no such thing as greatness, which is not to say that nobody and nothing can be truly special, but rather that all moments, all experiences, all of our daily intimacies and disappointments coalesce like paint or photographic chemicals into the image of a life, and that is good enough. In effect, queer formalism owes everything to second-wave feminism, which reminded our elders that the personal is political, despite the marginalization of feminism in contemporary queer and trans discussions.

“Above all, I want to foreground that queer formalism is not a democratization of culture, for an appeal to democracy brings with it elitist, racist, transphobic, homophobic, and sexist notions of taste and subjecthood. An appeal to democracy relies upon subjecthood, a concept that continues to exclude many bodies, especially trans and/or black and brown bodies. Moreover, an unstated underpinning of any “democratization of culture” retains a division between the cultural elite and Others. The former, in a presumed gesture of radicality, debase themselves with pop culture, while those who consume pop culture do not know that their aesthetic choices are the source of one of the biggest academic debates since the nineteenth century. Ultimately, it boils down to that archetypal situation wherein you love John Waters, David Lynch, Nicolas Winding Refn, and Harmony Korine, for instance, but you hate everyone else who loves them. Korine’s Spring Breakers, for example, is so smug, but even more smug are fans of the film who purport that you should still love it despite its sexist and racist phantasmagoria. Unfortunately, I find myself in and identify with the cultural landscape that Korine portrays in his film, which is comprised of vulnerable women who want more than anything to be beautiful and dangerous and sad, who want to be a Lynchian heroine (hence my naming this volume after Twin Peaks: The Return, Lynch’s 2017 follow up to the 1990s cult series), who became “cool” through racial appropriation. Though a millennial audience might most forcefully understand the film’s references, the more general “point” is the shift in the early 2010s toward the diaristic or the film equivalent of autotheory/autofiction, which is perhaps epitomized by Lena Dunham’s Girls, whose first season premiered the same year as Spring Breakers. That same year, 2012, Lana Del Rey came along, and as a culture we decided that we loved it, but that it was all ironic and problematic. And yes, it is those things, and queerness is those things too. A fascination with fragile white women, for instance, from Judy Garland to Britney Spears, is both sexist and racist, and it has defined a certain strand of gay male culture for decades. And no, Kayleigh, you did not have a “Britney moment” when you trimmed your bangs by yourself. I had a Britney moment when I shaved my head and eyebrows before overdosing on lithium.”

—Excerpt from William J. Simmons’s Queer Formalism: The Return, “Introduction (For Audrey Horne),” 2021

Liza Mullett: How would you define queer formalism to the unfamiliar reader? How has your comprehension of queer formalism changed since your first publication?

William J. Simmons: I think that the use of the term “queer formalism” is about being true to history. I wrote “Notes on Queer Formalism” when I was younger, and it had an impact on my and others’ thinking. I needed to contend with that at this moment of transition in my life. I am grateful to that text and I am grateful to my publisher Aaron Bogart for the chance to revisit. I had a very clear sense of what “queer formalism” meant eight years ago, but now I don’t. Back then, I was interested in the language of the manifesto, and now nothing could be more boring to me. I often accuse myself of being in my “return to order” phase: I live, laugh, love Jeff Koons and I feel no need to legitimize it. Evasion of questions is so pretentious, but all I can say is that I hope the reader defines whatever they choose however they choose.

LM: The book explores the idea of critique and the implications of critique, but you also critique your own work and your own understanding of queer formalism—i.e. your initial interpretation of painter Amy Sillman’s work in “Part II, How to Disappear.” Is it possible to create cultural and queer analysis without the personal? Are they inextricably linked?

WJS: This is a great point. They are inextricably linked, especially with work that aims to be political. As second wave feminism taught us, the personal is political, and the personal is discourse. Shame is likewise so much a part of the personal: the fear that you are out of the loop, uncool, missing the point, bamboozled, etc. Amy Sillman’s writing taught me that. Those negative emotions, which also form the core of how we do critique, can become generative ones though when we use them to forge newly empathetic ways of writing and speaking.

LM: You use such a wide breadth and depth of cultural references—from Gustave Caillebotte to Lana del Rey. From a technical standpoint, where do you begin with deciding who to reference or draw from? Does the reference come first, or do you draw from a mental library when needed?

WJS: I work intuitively, and it is my pedagogical goal to help create the conditions wherein others can do the same if they wish. In addition to the various forms of obvious violence and abuse that I experienced in my graduate programs, one of the more mundane traumas is the notion that the only things worth thinking and writing about are those that have achieved the narrowness of academic or intellectual verification. But if you have strong feelings about, say, Billie Eilish, and you can’t connect them to the conventions of a dissertation (or a thinkpiece or a self-aware podcast), I want that to be okay. Being a “mere” fan of a historical figure, movement, way of living, Billie Eilish, etc. is already interesting enough.

To this end, when I write, the mental library is all there is. I tend to selfishly smash whatever the parameters of the writing project are into whatever I am interested in at the moment. Sometimes it works and sometimes it fails spectacularly. In any case, I always try to think about how my relationship to culture in this specific instance might be broadened to appeal to more readers. The issue with the current fad for auto-theory is that the references become a closed autobiographical loop that oftentimes just performs the fact that you had an elite liberal arts education and you don’t know what to do with it. I certainly am guilty of this too, but above all, I hope that Queer Formalism: The Return, even the more squarely academic chapters, gestures toward something more general, even scare-quotes “universal,” about desire, regret and knowledge.

LM: With stan culture in mind, I’m interested to hear your perspective on Britney Spears’s current situation and the #FreeBritney movement. You comment on the gay male fascination with fragile white women, including Spears and the subsequent idea of a “Britney moment.” I am reminded of a quote from page 23: “The heteropatriarchy oftentimes uses interpretation, critique, and/or deconstruction in order to immobilize and silence the Other by turning them into pure discourse so that actual flesh and actual experiences can be ignored.” What are the implications of the silencing of Spears on this fascination, or the heteropatriarchy?

WJS: I think it is an instance, as you suggest, of a woman being turned into pure discourse. Britney’s autonomy has been taken from her because she has to exist solely as an image, a topic of discussion, a site of fascination, lyrics to scream in the club, something to reminisce upon, a doll to dissect and masturbate to. It is apparent that there is no culture without the abuse of women.

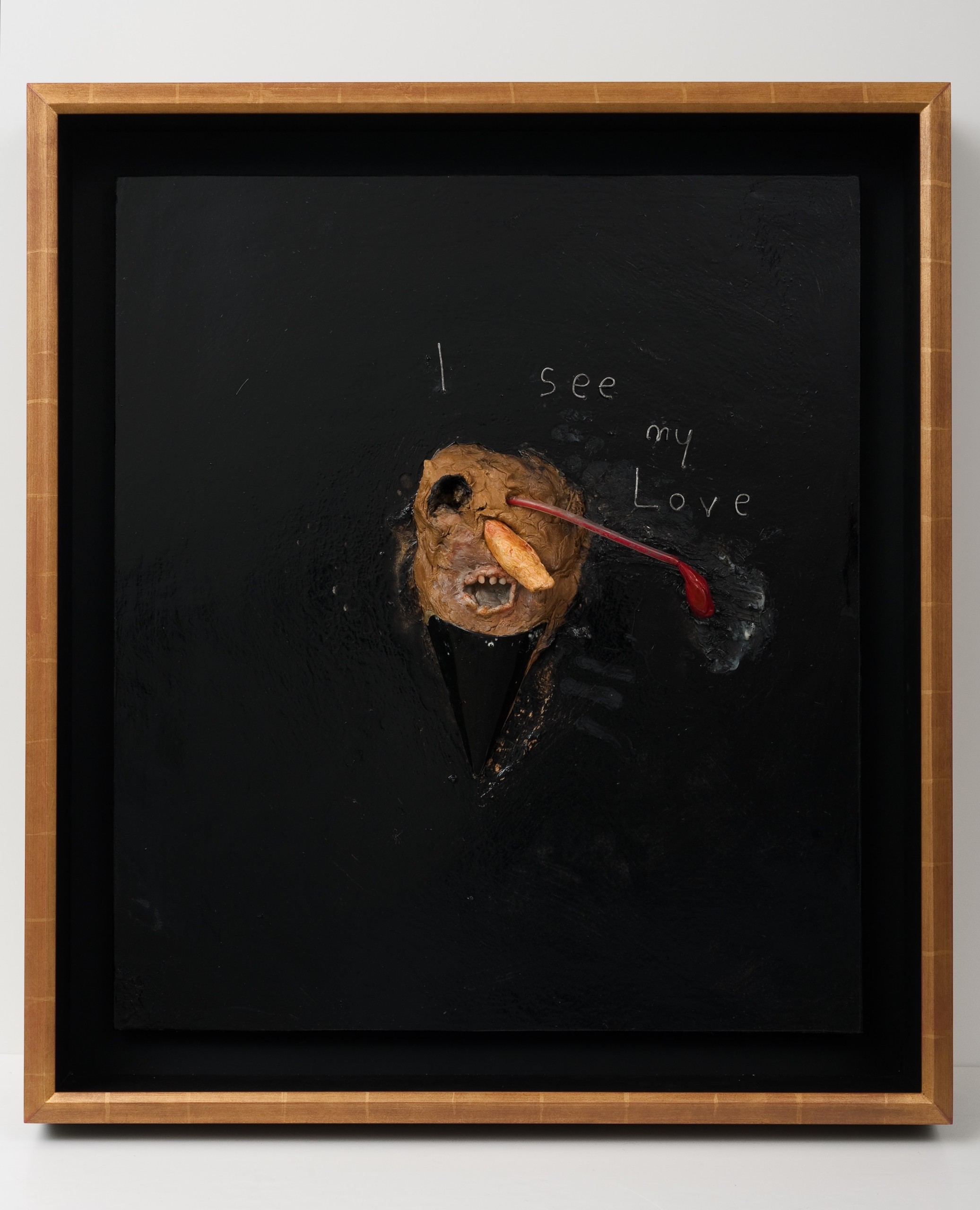

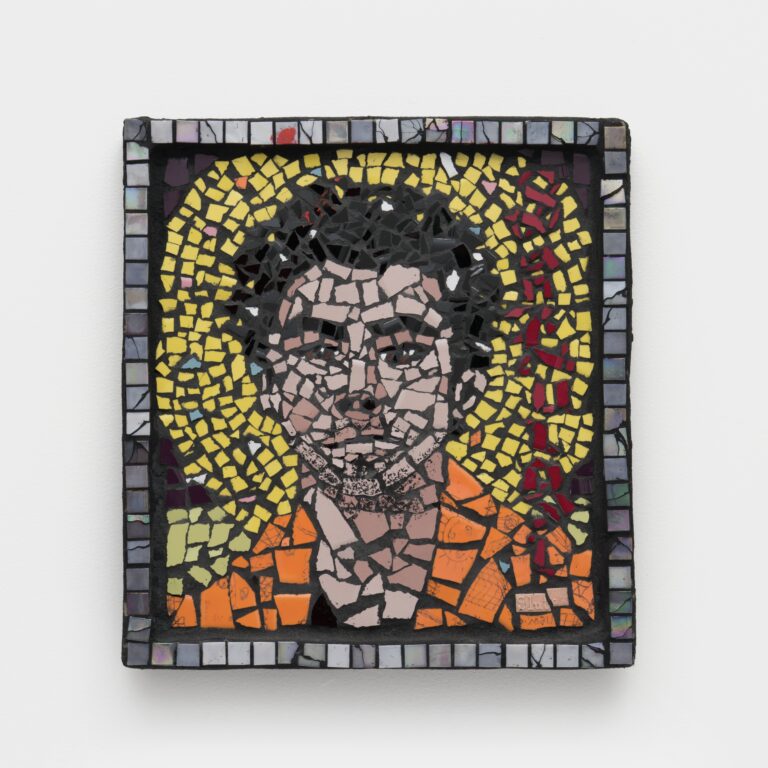

LM: The publishing of Queer Formalism: The Return coincides with your virtual art exhibition with Hook, “Desire/Aspiration/Love/Rejection.” What was the curation process like, given your study of queer art?

WJS: The exhibition has no lofty intellectual or curatorial aims. It is a cross-section of artists that I think about every day (queer and not queer), and it is a list of people I want to succeed and thrive. I wanted to get across though that one’s loves, no matter how disparate, connect because they are within the landscape of your mind; they are all within your/our thinking and feeling body. Luckily, Jake Nyquist, the platform’s founder, understood what I was trying to do and stood by the perhaps inscrutable combinations and juxtapositions.

LM: What’s next for you?

WJS: I am working on a book of essays and collaborations entitled Love and Degradation, as well as a novel about a murder in Los Angeles and being young and gay in New York.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?