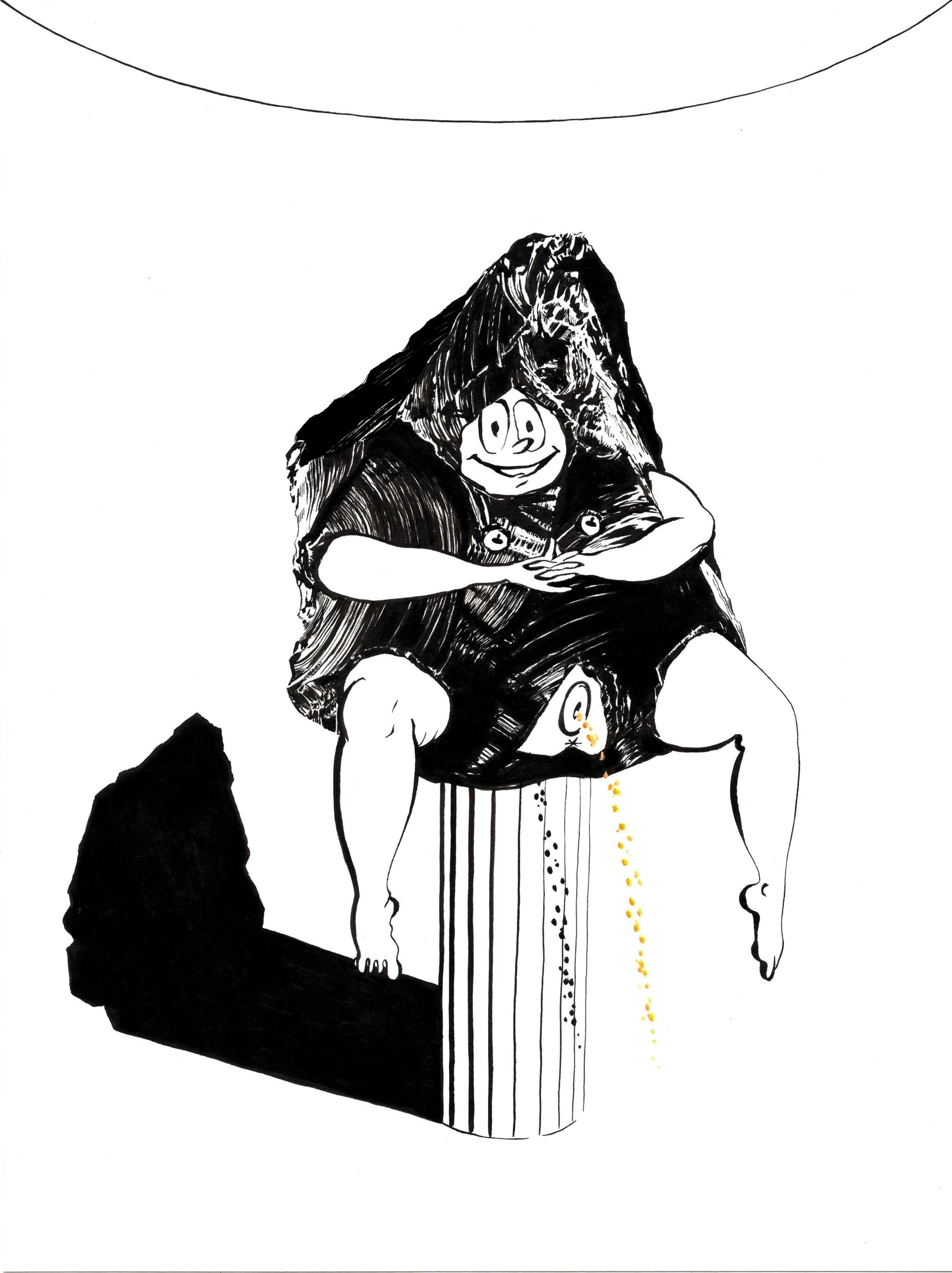

Ebecho Muslimova, FATEBE A STONE MIRACLE (Elagabalus rock), 2021.

Ambition was perhaps the only reference point shared between him and the 17th century French monarch who called to that central star for his power as well. Ambition was in Elagabalus’s genes, inherited down the matrilineal line (of course) from his politically aggressive grandmother and mother. His legacy is disjointed—historians, both ancient and modern, have reviled him, gawked at him and, on rare occasions, admired his audacity.

Elagabalus was born around 204 AD, very likely in Emesa (his ancestral home), now modern day Homs, Syria. He was born Bassianus, but the name he officially took when he rose to emperor was Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus. The name he came to be known as was derived from Elagabal, the obscure sun god he and his male ancestors worshiped as priests. To get to the meat of his story, you have to go back roughly a century to the assassination of the emperor Domitian, the last of the Flavian dynasty. The string of emperors who followed Domitian over the next 100 years were referred to as the Antonine emperors, of which Commodus was the last. Commodus’s father, Marcus Aurelius, is remembered as the philosopher king. His Meditations on life and the nature of existence are still read today, and advise a self-reflective way of living and mode of governance. Elagabalus’s senators and family hoped to project these same characteristics when they included Marcus Aurelius in his official name.

The Antonine rulers were successful at maintaining peace and order, mostly because they selected their successors from outside of their immediate families, favoring exceptional skills and intelligence over blood relation. Marcus Aurelius’s terrible choice to pass his power along to his buffoon of a son marked the beginning of an extended period of bloodshed and chaos in the ancient capital and its provinces. The year after Commodus was murdered in his own bath—193 AD—saw five different men claim the imperial throne in quick succession. Septimius Severus was finally successful in his bid, years after political unrest began.

Severus hailed from Libya, then colonized by the Romans, with an Italian Roman mother and a Phoenician (Punic) father. Many years before he ascended the imperial throne, Severus fell in love with a Julia Domna, an aristocratic teenager from the town of Emesa. Julia Domna was said to be beautiful and brilliant, persistent in her endeavors and blessed with a quick wit. While Severus ruled, Julia, by then his wife, cultivated a cultured court, attracting intellectuals with less unyielding beliefs than the Stoic philosophers of the preceding centuries.

Julia bore Severus two sons, Caracalla and Geta, to whom he jointly left his throne in 211 AD at the time of his death. Caracalla murdered Geta the same year, tricking their mother, Julia, into luring his hated brother into a trap. In a particularly cruel move, Caracalla further forbade his mother from mourning her dead son, though she was still in charge of the administrative side of running the state while her remaining son campaigned. Caracalla’s reign ended with his own murder in 217 AD, and Julia Domna, already weakened by breast cancer and with power slipping from her hands, committed suicide in Antioch.

The engineer of Caracalla’s death, a praetorian prefect of Berber descent named Macrinus, seized the throne on the 11th of April, 217 AD. Only three adult members of Severus’s family remained: Julia Domna’s sister, Julia Maesa, and her two daughters, also called Julia (Soaemias and Mamaea). The three Julias and their two young sons (one for each daughter) were sent back to their hometown of Emesa, where they were expected to dawdle in obscurity. Macrinus ruled jointly with his own son, Diadumenianus, for a year, before whispers started to travel from the aforementioned town. Julia Maesa, proving just as brilliant and determined as her late sister, was putting the building blocks in place to elevate her grandson, Bassianus (our Elagabalus) to the imperial throne. Her methods were simple: bribe the nearest legionaries. She offered them the treasures of Elagabalus’s temple, of which her grandson Bassianus was already the high priest. Macrinus was a miser. His pinched pockets, along with a new rumor—that Bassianus was actually the bastard son of Severus via a secret affair with his cousin, Julia Soaemias—was enough to flip the legionaries and senate. B

attle ensued in Syria between Macrinus and the Roman soldiers now under Julia Maesa’s command. As the battle turned, Macrinus tried to flee to Antioch, but was caught mid-escape and assassinated unceremoniously by the side of the road. It took nearly a year for his successor, already being called Elagabalus in the capital, to make his way to Rome. A portrait of the new emperor was sent in his stead, gossip about his character swirling around it. The image, now hanging in the senate, was one of a fine-boned youth, decked out in a purple silk tunic embroidered all over in gold thread, with kohl-rimmed eyes and black cropped curls.

Very few hard truths made their way to the capital concerning the emperor. As he lingered in Nicomedia (a coastal town in Turkey), the senators were left to wonder about the true character of their new pubescent emperor. What they did know was that he was attractive, young and devoted to his god. How devoted, however, was unclear. He woke up with the sun every morning to perform the ritual dances required of Elagabal, escorted by a host of young Syrian girls. When Elagabalus finally began his procession into Rome, he was accompanied by his god in the form of a hunk of volcanic rock. The obsidian idol was set up in the most lavish of temples overlooking the many places of worship for Rome’s countless deities.

Romans enjoyed and encouraged the worship of pretty much any god. There’s was a polytheistic leaning, with Jupiter, the king of the gods, taking precedence above all others. Unfortunately for the Romans, and especially for the senators, Elagabalus turned out to be a zealot. He forced the senators to pay tribute to Elagabal before each meeting and, in essence, to bow to him, Elagabalus, as the god’s representative on earth. Furthermore, he raised Elagabal, a foreign sun god, to the highest position in Roman religion. This first misstep was exacerbated by Elagabalus’s marriage to a Vestal Virgin, Aquilia Severa, in 220 AD. The emperor divorced his first wife, Julia Cornelia Paula (given the honorable title of Augusta upon her marriage in 219), for Severa, slighting Augusta’s powerful, aristocratic family in the process. Severa was the high priestess of Vesta, a cult whose primary responsibility was to ensure the safety and preservation of the Roman empire, symbolized by an eternal flame tended to by the priestesses. Even a momentary snuffing of that flame would spell disaster.

Vestal Virgins were called such as virginity was a requirement of their role. If one of them was found to have engaged in sexual acts with a man, her punishment was to be buried alive—a sentence that was carried out strictly. Elagabalus’s marriage to Severa was his first indication of sexual and religious irregularity. Even prior to the union, his agents throughout the realm kept their eyes peeled for any tasty morsel that might interest the emperor. Shortly after the marriage, a snack was sent his way in the form of a ruffian named Diocles. According to Cassius Dio (the premier gossip of ancient Rome), Elagabalus was besotted. So much so that he comfortably suffered abuse at Diocles’s hands; black eyes and bruises were boasted at more than one senate hearing.

Elagabalus’s procurers went a slightly different route next time. The athlete, Zoticus, was shuttled to the capital after news of his extraordinarily large “equipment” reached the imperial palace. Elagabalus wined and dined him in his private baths, but when it came time to perform, Zoticus proved a flaccid disgrace and was sent away tout suite. Next up in the marriage train was Annia Aurelia Faustina, another Roman noblewoman who Herodian, a civil servant turned historian, says Elagabalus married briefly in 221. She was a direct descendant of Marcus Aurelius and incredibly prominent as the widow of consul Pomponius Bassus, who Elagabalus had murdered shortly before his marriage to her. The following year, Elagabalus divorced Faustina and remarried his second wife, Severa, still shockingly above ground.

To top it all off, Elagabalus saw it fit to host a fifth, public marriage, this time to another man, Hierocles, a former slave who had recently risen in status to charioteer of the emperor. Hierocles was said to be blonde and fair, with a powerful form and physical prowess. Elagabalus reputedly referred to himself as the “wife” in their affair, which fell in line with Dio’s claim that the emperor responded to Zoticus upon their meeting, “Call me not lord for I am a lady.” Dio also claimed that Elagabalus dressed frequently in female garb and was willing to offer vast sums to anyone who could outfit him with working female genitalia (though this last bit is heatedly disputed). He even went so far as to renovate an interior wing of the imperial palace to look like a common brothel, with himself—entirely shaven, oiled and painted—as the primary attraction.

Throughout Elagabalus’s ongoing, colorful romantic affairs, Julia Maesa was doing everything she could to hold on to power. As it became more apparent that her grandson was unfit for political leadership, other options were considered, namely Elagabalus’s cousin, Alexander. Elagabalus was made to adopt Alexander as his son, which initially tickled the emperor, as his new son was only a few years his junior. He realized too late that implementing this Roman tradition of adoption was a move to displace him. Alexander was carefully guarded by the Praetorian Guard (who had been bought by Julia Maesa). Any attempt to access Alexander was met with indignation and uproar from the troops. At some point, the emperor felt compelled to restore order himself. He confronted the guards at their camp with his mother, Julia Soaemias. We don’t know exactly what transpired, but at some point things took a turn for the worse.

Elagabalus tried to flee the situation in a chest carried by nervous slaves. His mother, frantically attempting to shield him from Praetorian advances, perished, as he did, at the point of the guards’ swords. Elagabalus was slain at age 18 on March 11, 222 AD. Both his and his mother’s bodies were decapitated and dragged naked through the streets of Rome. His mother’s corpse was thrown into an unknown ditch and his was tossed into the Tiber. Postmortem, he would come to be known via his final resting place: Tiberinus. Many of his associates were soon unseated or murdered, including Hierocles. Elagabalus’s cousin-son, Alexander Severus, was named emperor, ruling with his grandmother Julia Maesa and mother Julia Mamaea. Damnatio memoriae (a practice also found in Ancient Egypt) was activated after Elagabalus’s death, meaning that all traces of him and his life were erased or reconfigured within the capital.

In the last century, study around this saucy son of Rome has taken a notably homophobic tone. Though his brief reign was looked on contemporaneously as problematic, when viewed through a modern lens, there is much to be admired. The freedom with which Elagabalus explored his sexual appetites was at times radical and at others impressive. Imagine being thrust to the helm of the “civilized” world just as puberty hits. The access to power would have been intoxicating, even for a grown man. For a boy (or a gender nonconforming person, as might be the case here) it was likely impossible to navigate. Rather than the freakish example of late Roman decline that he’s been painted as, Elagabalus should instead be viewed as a unique case study for non-binary experiences in the ancient world, as well as the victim of political machinations far beyond his youthful comprehension. His short life gives us proof of an ancient spectrum, just as it shines light on ancient prejudice, providing fodder for contemporary narratives outside of the binary.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?