Rose Leadem: How do you two know each other?

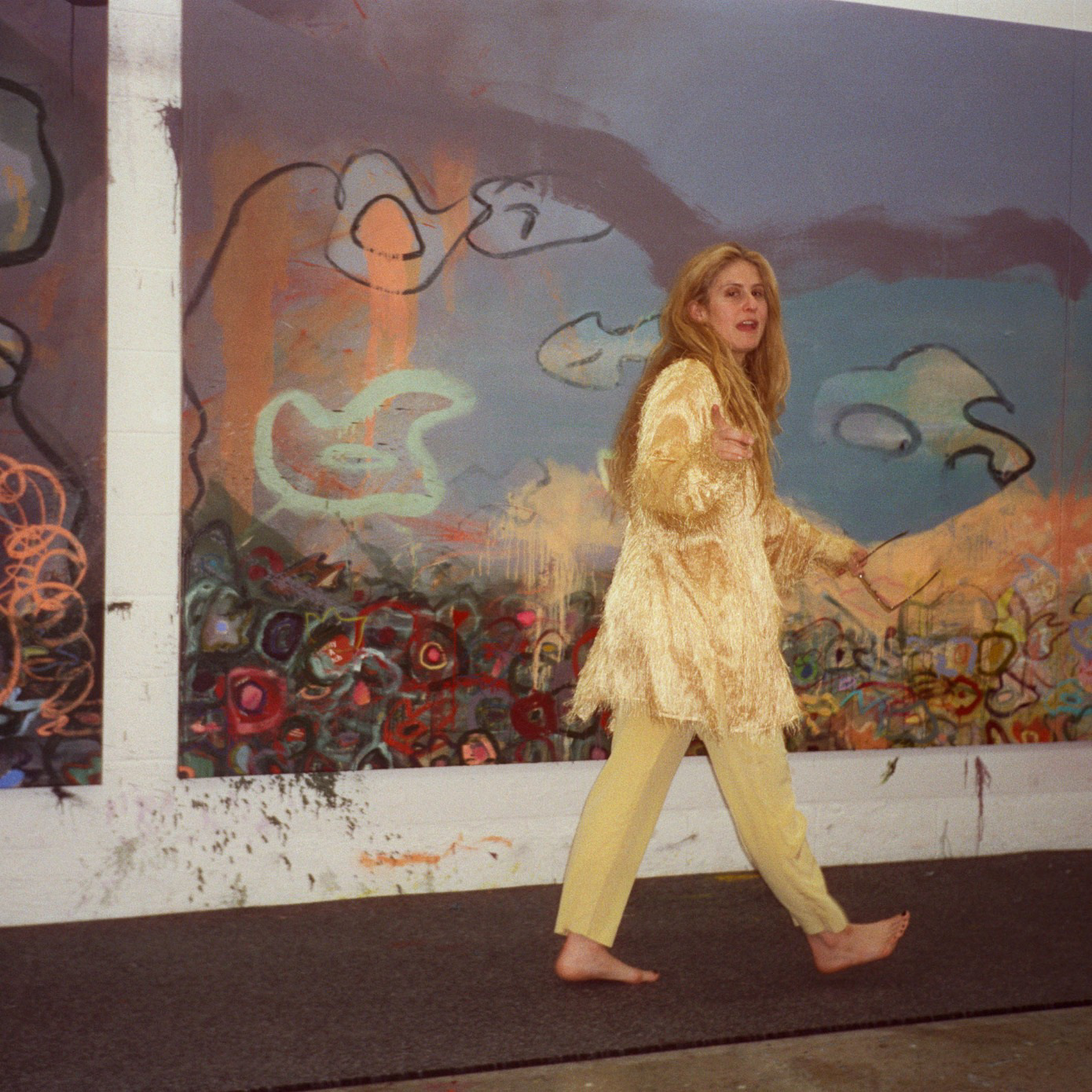

Francesca Gabbiani: We met at the Hammer Museum at an opening. I’d heard about you [Dana] because of a solo show I'd had in New York, at Marianne Boesky Gallery. I was told that you liked my work, but I'd never met you. A few years later, as I was walking out of the Hammer Museum, I heard someone yell my name, and it was you!

Dana Goodyear: It must have been shortly after that, though, that I asked if I could use a work of yours as the cover of [The Oracle of Hollywood Boulevard: Poems]. So, this [Lost Hills podcast] collaboration is not a first.

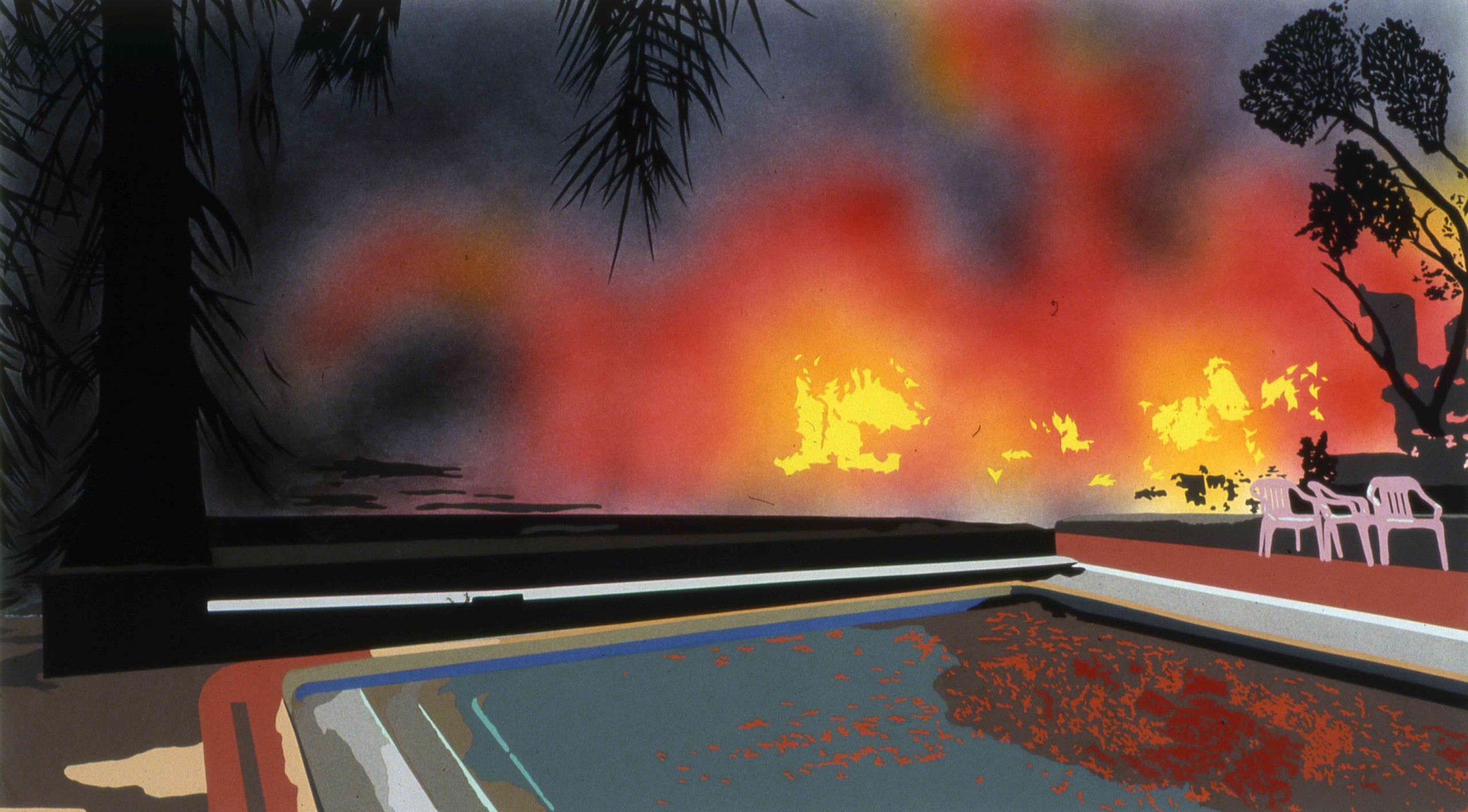

DG: How did you start making fire paintings?

FG: I made the first fire work when I was living in Echo Park in early 2000. I was living in Silver Lake when Griffith Park caught on fire. It was in 2007 and we could see the fire from our home. We could actually see Griffith Park burning from our house. Then, while I was teaching at the Armory Center for the Arts, I hiked Eaton Canyon with the students and there was this eerie, smoky, weird light all around us, which was quite beautiful, but in actuality it was a fire. Fire is very surreal because it has this beauty to it — the light, the ambiance, the science fiction-like landscape it creates.

DG: I think the works I had seen in New York—you were kind of out-of-place and out-of-time, to me, I didn't know you were an LA resident—were your interiors. It wasn't clear to me because I didn't understand it was work about California, but then when I got here and saw more of it, what you were doing resonated so much with the story of California that I was finding myself drawn to tell in words. And—exactly what you were just talking about—something that represents an incredibly destructive force that's going to have a huge impact on humans and other animals, but also comes out of, in some way, our own behavior, which helps create these conditions. It's impossible for me not to notice the intense beauty of what those sunsets look like over the ocean when there's a fire or all of the moments of pathos too. The cover of this book—the deck chairs with the ash on them—conveys this Pompeii feeling that you can have pretty regularly living in a place as unstable as Los Angeles. Noticing that there was someone else who was on that same exact frequency, but able to render it visually with these incredibly precise cut-outs and the painstaking carefulness of it—I really responded to that.

FG: I think that there is a story to tell with the fires in LA—a dark story. Often in science fiction, there is a dark story, but there is also a philosophical side. For instance, in Octavia Butler’s—who, by the way, became a best-selling author last September—Parable of the Sower, there is “Earthseed,” a fictional religion based on the idea that "God is Change.” I re-read it at the beginning of the pandemic and it felt so incredibly psychic and so in-line with the stories I’m trying to tell in my work. It’s a very post-apocalyptic story. It’s set in Los Angeles and there are fires everywhere; some of the characters take this drug called “Pyro,” which makes them have orgasms when they light fires; people are forced to walk on the freeway to getaway from the people addicted to Pyro; the society lives in small communes, and this is also where kids are taught as there are no physical schools—so much of it was like our reality during COVID. You walk outside and there's a wildfire raging in Malibu, your kids are going to school online, and you're starting to grow your own food because grocery stores are empty. You avoid people at all costs because there is an epidemic.

RL: In addition to fire, you two also have the bond of the ocean, of water?

DG: I think they're a natural pair. What do people do when there's a huge fire in the hills? They run to the ocean.

FG: They go to the water.

DG: It feels like the other side of that equation is the healing. It resolves the storm on land—the fire is resolved in the ocean. But it's also just a lovely friend to have; a lovely way to experience friendship. Being in the water.

FG: Yeah, and it's funny because in Barbarian Days: A Surfer’s Life by William Finnegan there’s a sentence where he says, "There were some really old people who started surfing when they were 14 years old." I was like, we're the dinosaurs! But it's kind of fun, we all have busy lives. We put our kids on boards early because the ocean is an important part of the LA landscape and lifestyle. It was very important to me that they learn about the ocean, and once the kids were taken care of, then it was our turn. Forever, I would go out with my kids on the board but never really caught waves because I felt like I didn’t know how to do it. There are all those surfer dudes in the water who are very territorial, but little-by-little I was like, “Oh, whatever.”

RL: Dana, how did you start surfing?

DG: When I met Francesca I was living on Hollywood Boulevard, and then, in about 2011, I moved to Venice. That year my husband bought me this beautiful pink surfboard. I was pregnant with my second child that Christmas, and as soon as I had my daughter, I went and got a wetsuit. So I was just learning to surf for the first time at 36. I go by myself occasionally but I really like going surfing with other women. Usually that's what gets me in the water. Once I found my intermittent on-again off-again crew of women that I like to surf with, it became something that I began to do all the time. Also, during the pandemic, when I really needed something that wasn't my house, that I could immerse myself in completely—literally and figuratively immerse myself in something that wasn't my home or my work—going to the ocean was a really good way to find some internal space.

Before the pandemic, about a year after the Woolsey Fire in Malibu in 2018, I think you'd seen some of my reporting for the fire and asked if you come with next time. Then, there was a fire in Crestwood, which is this very specific “architecturally controlled” community in Brentwood that has a fascinating history. There were some really amazing, pristine, mid-century modern houses that were destroyed in that fire, and because I had a press pass, we were allowed to cross the lines, so Francesca and I did some fire reporting then. I think that's the point at which we started talking about surfing. How we started surfing together was doing fire reporting together.

FG: I got lucky that Dana said, “Come over, let's go to this neighborhood!” I took a lot of footage and photographs over there, which will be in my upcoming film, Sea of Fire, and for which I’ve used as source images for some of my works. I vividly remember a car we came across, that was completely melted. The same tar from the road, which is usually under a car, was on top of it because it had burned in a garage with a tar roof. All of the grays, all of the colors of those post-fire burns are interesting to me. Everything is almost black and white—or blue and white. Then, a few weeks later, when there's one drop of rain, not even two drops, fluorescent green life starts to grow from the ashes. Nature is so resilient. It’s very poetic.

DG: I remember that day you were talking about and taking pictures of the way that the fire had transformed these man-made objects—like the car with the roof melded to it—almost making them a part of nature in some way. I was really struck by that observation. How these manufactured forms were rendered organic by this incredible force of the fire and turned into something else entirely.

FG: Yeah, that’s something I’ve made work about for a long time, man-made materials that either look like they’re from nature or that have literally infused themselves with nature. Like, “Is this an agave leaf that's coming out?” It really looks like it is a burned agave, but it's actually a piece of melted plastic that has mirrored the shape of the cactus next to it.

DG: That kind of feels like what you were talking about—like there's a moral to the fable and maybe the moral is about the inescapable patterning of nature and what it can do to something as alien as plastic.

FG: That's an interesting fable to be painted.

RL: How did you both end up in Malibu?

DG: I don't live there. I just hang out with Francesca there, and then go and do my reporting there.

FG: My husband, Eddie, and I have a house in Malibu that was recently handed down to us by our family. But actually, when I first moved to LA in 1995, I would drive around everywhere, as I’ve always been incredibly interested in architecture and landscapes, and I found this place called Big Dume, completely by chance. It wasn't an obvious part of Malibu—it was not a place that you could find easily. There was a super broken staircase I found there, which is so broken now it's kind of impossible to go down. I used to go to that staircase with people, I would even bring dates there. When I heard that Eddie's family had a house near there, I was like, “What!? I love that place!” It’s magical, apart from the people who act entitled, though there are many people who do not act that way. Malibu really has an incredible magic to it.

RL: Do you both surf together there?

FG: We have. I mean, I'm a very debutante... dinosaur.

DG: Same, but it is a very beautiful little spot there, you can understand why people do guard it jealously. I think that's the only place where we've surfed together but I keep envisioning a women's road trip to point south.

FG: Yeah, or Carpinteria?

DG: Yeah, or points north.

RL: The Surfette series— are those based on photographs you've taken or images you've found? Are they mostly in or around Malibu?

FG: They are both photographs that I’ve found and pictures that I’ve taken. I was walking on the beach a lot during the lockdown and I saw this woman surfing with no fin on her board. She was so graceful. She made me want to draw her, and, at the same time, I was reading Set the Night on Fire and learned how people of color were not allowed on the beaches, nor were they surfing. So, I decided to mix all of that together and create my Surfette series. Frankie Harrer—she is the “graceful” one I mentioned. I tracked her down—I didn't know her name, I didn't know anything about her. She really was a little ray of sunshine for me in the beginning of the pandemic.

DG: Did you make up that word, “surfettes”?

FG: Yeah.

DG: I like it.

FG: Thank you.

DG: I've been reading now a lot about the ‘60s and ‘70s in Malibu, and surfboards used to just be these giant planks that weighed so much and were like 16 feet long. They started making surfboards in Malibu out of balsa wood and lighter woods and those are the ancestors of the boards that people ride today. But they were called “girl boards,” because they made them for the couple of women who surfed, and they thought they needed to be lighter for women. They noticed that the women could carve on the face of the wave, as opposed to just straight line because the board was lighter and had fins and everything. It's interesting that as much as women are erased from a lot of surf history, there's actually one example of something that became the normative version—this version that was designed for women. Even if that's kind of secret.

FG: They would never want to admit to that. Well, it's true that the fin helps. But then they went back to short, short, fast, fast. Shorter, faster.

DG: Potato chips. I think women have always been integral to the history of surfing, like the Polynesian part of the story.

FG: Yeah, they were surfing too. Everyone was surfing. And then the colonization happened, and all of the diseases, and then surf got completely eradicated.

DG: But you can tell when, on a day when there are a lot of women in the water, the vibe is so different.

FG: The openness. It becomes a different territory.

DG: The physical feeling that you get when you have the thrilling experience of riding a wave is so... I mean, people talk about it like a drug. You can understand, even if you don't like it, why people get so edgy. They want that thing; there's only one.

FG: There's only one.

RL: This idea of politics in the water and in surfing—a hierarchy with the waves. Do you think this compares to any sort of hierarchies within art?

DG: I think that if the hierarchy gets established by who's had access longer then it reinforces all of the structural inequities, so it's not going to be women and it's not going to be people of color. It's going to be mostly...

FG: ...Older white males.

DG: And they have been the ones surfing there for 40 years. But it's interesting too: different spots have different makeups. There is more of a mix in the water at most of the places where I surf, than maybe in Malibu. I think maybe it's Francesca as a Swiss woman bringing the diversity.

RL: Speaking again of Malibu, how did your Lost Hills collaboration emerge?

DG: Francesca had invited me to come and surf near her house and on the path down, which is this very beautiful, wooded, green path, which feels like a portal into another world, I said I had another cover-art project for you. Not long after we spent that day in Crestwood, fire-reporting together, I came and did a studio visit, and I took a picture of this fire painting that I was crazy about and I had it as my screensaver on my phone. And eventually I realized it would be the most amazing cover art for the podcast. But Francesca being Francesca, she took that to a whole other level and hiked out to the suspect's camp a few times, and made work about that, and really investigated every aspect of it.

FG: It is an interesting project that I felt very honored to be a part of because I am certain there is something to be unraveled about mistakes done by the police, and it is an important story to be told.

DG: There is a dark story but you weren't put off by that. A lot of people would say, “I don't want to talk about that Malibu.” But you were sensitive and tuned into the shadow side—maybe even excited by the shadow side.

FG: This is the thing about Malibu that's interesting—it's beautiful, it's magic, but there's also an underlying darkness to it. There is an undercurrent to life in Malibu that is depicted in Lost Hills. If you start scraping just a little bit at the surface, it's not all golden and shiny, and I'm interested in that. It's like when you look at nature and you see pieces of metal that have wood growing around them, and you no longer know how to separate the two. There is a similar thing in my work.

DG: The attractive and the repellent are fused together in a way that you can't separate.

RL: In addition to the natural elements that draw your different mediums together, you both share this interest in darker narratives, diving deeper into the darker side of California.

FG: When I moved here, I was driving everywhere and looking at everything. One of the first houses that I recognized was from The Killing of a Chinese Bookie. That house doesn't exist anymore, but it was a beautiful house. I read all of the James Ellroy books before moving to LA. And then, I would find other places from his books, like Pink’s Hot Dog stand. To me, everything had this filmic, dark narrative toit. Hollywood Babylon by Kenneth Anger also comes to mind.

RL: Francesca, you have your own astonishing story of hiking in Griffith Park and finding a severed head. Would you care to share the story? Have you two exchanged these Noir notes?

FG: That was the typical LA story. So much so that I didn’t know if the detectives that showed up on-site were actors or if the movies were imitating real life or if real life was imitating the movies. I was hiking early morning with my dog, and it was the Monday after Thanksgiving so the park had been without rangers for a long weekend. It was at the beginning of my hike that a crow was calling me and my dog. It wanted to show me what he had caught but I didn’t really pay attention and kept hiking. On my way back, it was calling me again, “Caw, caw, caw, come and see what I got you!” So I went...and that was that. I found a severed head. I called 911 and the cops and detectives showed up. The crow, the detectives’ cars shiny as black mirrors, their impeccable pompadours, their suits ironed to perfection, their greenish pale faces—they live by night and don’t sleep much—seemed all out of a movie.

RL: When you're studying these subjects, is it possible to maintain a sense of detachment?

DG: I don't feel detached. I feel like I stay really curious, and I think that that's a kind of lighter, faster frequency than getting completely mired in a sense of tragedy because, for me, there's always that quick pulse to find out more and that is almost like a fuel to my storytelling—that curiosity. But I had more fear working on this project than I've ever had working on something because there are very real, possible consequences. I am very aware of how impossible it would have been to tell this story living outside of LA, because it took time, and I had to be around, and I had to keep painting on one layer after another of exposure and experience with the people that I knew needed to be at the center of the story. It would not have worked if I still lived in New York. That's just not the nature of it. I had to be close at hand. But once you're close at hand, it means you're wrapped up in the story and you're a known quantity, and there's nowhere to hide for me. So, I did start having very personal feelings of anxiety and fear around engaging so intensely with someone who's accused of violent crimes, including murder. That's getting close to the family of someone like that, not meaning that I'm afraid of them at all, but just this sort of psychic involvement. And then the law enforcement side of it, there are some people that I think are very decent and even noble in the tale, and then there are others who I think are very problematic that I know have done bad things, and that is nerve wracking. So, I don't feel at all detached. I feel way too involved.

FG: I'm not in the same position because I'm almost looking at objects. The same thing happened when I found the severed head in Griffith Park—immediately my brain saw it as an object. When I was a student in Geneva, I did anatomical drawings of cadavers. My father is a scientist and he challenged me to learn anatomical drawings like the old masters, with actual bodies and body parts. This taught me how to remove myself emotionally from the subject. But also, when I'm working on something, I am not doing any investigative work. I look at nature. I look at this particular mingling of stuff, and I look at it from above if it gets too intense. For instance, when I went to Afghanistan, I came back and had some serious nightmares—and I wasn't even there for very long, I was there for five days. And my doctor said I had PTSD. I'd never been to a country at war, and just driving around, you see things that are very shocking. But that's not how I do my artwork. I mean, yes, I talk about dark things, but they almost become a kind of narration.

DG: You're interested in horror, too, and you have been for a long time, so how did you get into that as a medium?

FG: I loved Dario Argento but I couldn't even watch a movie so finally I decided to make stills. I watched second-by-second, and studied the decors. That's how I took a step back and was able to work with those things that I was interested in. And then, effectively, when I was reading James Ellroy or any other dark thriller—before moving here, it was a different thing. But when I moved here, I was having a freak-out and I couldn't read those books anymore because they're too real.

DG: Do you think that working with dark material and ruins and fire-scapes is like what you did with the film stills? Is it a way to conquer your fear?

FG: Yes, possibly. I'm interested in this fragility of the urban. There are a lot of things for me that come into play—like all of those abandoned spaces. That's where I went when I was a teenager to go live with my friends that were also runaways. But that was in Switzerland. Not America. There were a lot of drugs around and stuff like that, and it was not the safest place, but it felt safe. So, there are two sides of this... moment.

DG: I am really afraid of this exact kind of story that I am now telling. People keep asking me about the Golden State Killer story: I'll Be Gone in the Night. My husband keeps asking me to watch it but I cannot watch that. I can't read the book, I want to read it because I respect the investigative effort, and I think it's incredible, and I think it's terrifying that the stress that the author was under when she was solving this unsolved series of horrific crimes eventually killed her. She died in an effort to produce this work. I feel that I should read it for that reason alone, but I can't. So, the question that I have for myself: Why am I attracted to a story the murder that’s at the center of Lost Hills? I think it is partially about slowing it down enough, stopping the frame enough, that I step-by-step conquer my own fear of these kinds of forces that we live with. Randomness and violence and mental illness. And the fact that nobody's actually looking out for you. You think you're safe because you're somewhere beautiful, but you're not. And writing and thinking about these things that are pretty deep fears of mine is a way of testing the bruise over and over again. Does it still hurt?

FG: I think, psychologically, that's a good way for you to approach it. Maybe it’s become more mechanical but if I am confronted with this, I will have to really slow it down until I can try to look at it from another perspective. But you're closer to that than I am because you’re an investigative journalist.

DG: I do think that there's also just something primal about these fears. Like I had my daughter, who is very afraid of spiders, come and look at the spider [in your film].

FG: I mean, why do I have a spider? I'm terrified of spiders too.

DG: I figured you probably were, and that's why I wanted to show her because it's also comical. At first, it's really scary, but at the end, when it's on the skateboard, it's like we’ve tamed this thing. It’s domesticated. It's cute. It's on a skateboard. And then you have this beautiful, graceful woman—who reminds me of that spider—on her surfboard. I thought it would be helpful to my daughter who really won't go upstairs after the sun goes down, and she's scared of spiders. I feel reminded by her fears that these are just primal fears. How do you confront that, or how do you deal with that, on each level of your life? How do you go even deeper into it? There are a lot of really important stories, but it's just that tug towards something primal that I think made it feel like I could spend all this time on this story. I could justify the total immersion into the world because I am getting something out of it as a human, not just as a service, for people to know this story. For me, there is something to be worked out internally about how it all operates.

FG: I think, for me, it's like: what's even going to happen to this city? Are my kids going to have to immigrate up north? Is LA going to become a ghost city? Are we not going to have water? Is plastic really going to become wood? I mean, what's happening? What is this urbanism that doesn't make any sense, that is all around us? What is this air that we're breathing? That type of fear. Maybe that's also something that pushes me to look at the little details, or to zoom-in in such a way that...

DG: ...that you don't get overwhelmed by the whole picture?

FG: Yes.

DG: It's interesting to be having this conversation while we're sitting here in what may be one of the last phases of this pandemic—or may not be, we don't know. And we're all sitting here masked, having a conversation about what if we couldn't breathe the air around us. This could become more normal than not normal—needing to protect ourselves from the environment or from each other on the level that we've all gotten accustomed to. And also, it's just wonderful to be having a conversation in-person because for a long time, that wasn't even a possibility.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.