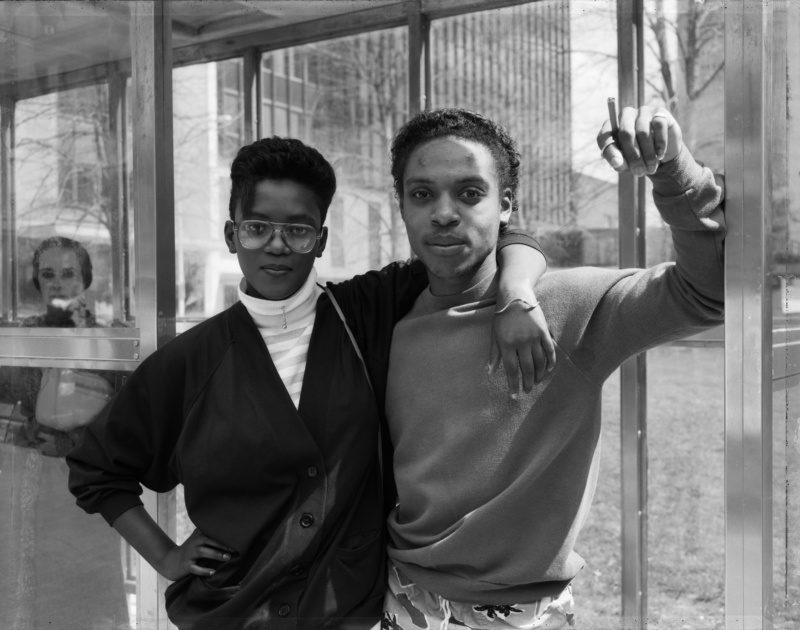

For over 40 years, Dawoud Bey has dedicated himself to creating nuanced portraits of marginalized realities. The artist found his footing during the 1970s as a young photographer in New York City, where he roamed Harlem’s streets in search of fleeting moments to turn his 35mm lens towards. While Bey belongs to an influential generation that disrupted the hegemony of white patriarchy within the institutional and commercial art worlds, his practice has always been defined by a style of its own. In his mostly monochromatic images, soft interplays between light and shadow draw viewers’ attention towards details that, taken together, highlight the idiosyncrasies and daily rhythms that make up Blackness in America.

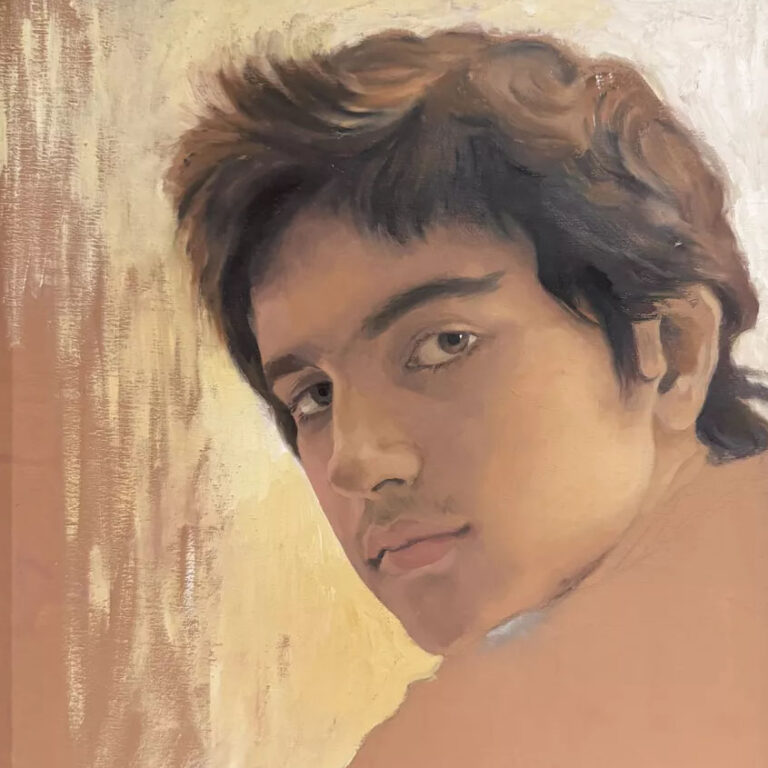

In later years, Bey expanded his practice by taking his camera elsewhere in the United States and around the world. Street photography eventually gave way to a studio practice, which resulted in poignant series: colorful Polaroid portraits during the 1990s, compositionally inspired by Rembrandt’s paintings, and Class Pictures from the 2000s, which utilized the photographic medium as a means to socially engage young people in powerful, three-way exchanges between the artist, institution and community. Over the last 10 years, Bey began to directly confront the nation’s legacy of racism and violence towards the Black community through disquieting, yet moving, images that convey the tragedy of the young lives lost to the Ku Klux Klan’s 1963 bombing of a church in Birmingham, as well as the glory of journeys towards freedom along the Underground Railroad.

Soon before the opening of his retrospective “An American Project” at New York’s Whitney Museum—the last stint of an exhibition tour that began at the San Francisco Museum of Art and passed through the High Museum of Art in Atlanta—I turned to Bey for answers regarding his ruminations on life and art.

Vivian Chui: Let’s start with the beginning. You were born and raised in Queens and came of age during the 1960s and 1970s. What was your youth like, and would you say that it informed your later approach towards artmaking?

Dawoud Bey: I’m certainly a by-product of those tumultuous decades. My youth was, on the one hand, largely uneventful, and, on the other hand, full of the drama from being in the first generation of Black kids to be bussed into largely white schools. Whenever I turned in an exceptional homework assignment, the white teachers assumed I must have copied it from somewhere. They had no idea that I probably had more books, and of more kinds, in my home than they did in theirs. I was constantly being scrutinized and misjudged. It was a real Twilight Zone-like experience.

By the time I was a teenager, I’d had enough, and was in full rebellion mode—staging sit-ins at my high school, locking the principal in his office with other Black students and progressive white students, demanding Black teachers and giving students a more active voice in their education, participating in the Vietnam War Moratorium, and joining the Black Panther Party. It was a time of social upheaval all over the country, and that was my life—participating in that moment. The saying at that time was, “You’re either part of the solution, or you’re part of the problem.” So, I was determined to be a part of the solution, to change the status quo.

VC: Were there any specific “aha” moments when you realized that your calling was photography?

DB: The moment that photography came on the radar for me was when I went to the Met at age 16, to see the “Harlem on My Mind” exhibition. It was the first visit to a museum on my own, and the first time that I saw images of ordinary African Americans on the walls of a museum. It began to give me a sense of what I might do with the camera that I got from my godmother years before, as well as a radically different sense of the museum. Though I had no idea how it would unfold, I began to think about photography in a different way, and that set me on my path.

VC: Some of your earliest works were created throughout Harlem during the 1970s. What was it about that specific neighborhood that drew you in?

DB: My parents both lived in Harlem before I was born, and met in church. We used to visit relatives and friends there when I was a child. So, the neighborhood is a part of my own personal narrative. I wanted to both revisit the place of my family’s history, while also contributing something to Harlem’s long history of cultural and artistic production. Two things that interested me were making photographs in which some aspects of the past were visible in the present; and also, to create work that constituted an honest and non-stereotypical representation of that Black urban community, which was too often described through a lens of social dysfunction and pathology.

VC: Around this same time, you began to meet and befriend many contemporaries—David Hammons, Kerry James Marshall and Lorna Simpson, to name just a few. Could you describe that moment in New York City?

DB: New York in the 1970s and 1980s was extraordinary. There was a vital conversation going on between the group of Black artists that I came up with, regardless of medium. The poets, musicians, painters, sculptors, photographers, dancers… We were all one community, and met each other within the context of the institutions that gave us a collective place. The Studio Museum was very much at our center, as were Just Above Midtown gallery, the Alternative Museum and Exit Art. These were organizations that came into being to support artists of color, when mainstream institutions were not even aware of any of us. We pretty much built our own community, because we knew that we didn’t have anyone if we didn’t have each other.

VC: Are there any artists, both from your cohort as well as from older generations, that particularly inspired you, or changed your practice in some way?

DB: The first artist who deeply influenced me was Roy DeCarava. He was the first Black artist to make photographs purely as an expressive act, not as a photojournalist. He had developed a unique visual and material language to talk about African Americans in photographs, in a way that was poetic.

They were a generation ahead of me, but I befriended some of the photographers in the Kamoinge collective, particularly Lou Draper, Shawn Walker, Tony Barboza and Danny Dawson. They became, for me, affirmation that there were Black photographers out there who were making meaningful work. Through the Studio Museum, I met Jules Allen and Frank Stewart, who at that point had more experience so I learned from them; as well as Carrie Mae Weems, with whom I’ve had an ongoing dialogue that has continued over these decades.

VC: And outside of art, what are some things that inspire you?

DB: I actually began my professional creative life as a drummer. John Coltrane—the power of his music, the extraordinary technical facility and his acknowledgment that there was a moral and spiritual imperative to his music—had a profound impact on me. Saxophonist David Murray is probably the contemporary jazz musician who most inspires me; I never miss an opportunity to hear him play.

When I’m in New York, I can usually be found at one of the jazz clubs. The Village Vanguard, which is a kind of sacred space; Jazz Standard, which has now permanently closed due to the pandemic; or Smoke, on the Upper West Side. In Chicago, I’m a regular habitué of the Jazz Showcase. Jazz clubs are my thinking rooms.

VC: I want to talk about a few important series from your practice. Young people have always had a presence within your work, but they became a primary subject during the 1990s and early 2000s. How did Class Pictures come into being?

DB: I began working intentionally with young people as the subject of my work in 1992, when I was invited to do a residency at the Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips, in Andover. That was the first time I spent an extended amount of time making work with and about them. I realized that they had not only been essentialized, but also left out of the conversation around contemporary art. In Class Pictures, I set out to represent who American high schoolers were at that particular moment—to not only make portraits of them, but to bring their actual words and voices to bear on how they wanted to describe themselves to the world.

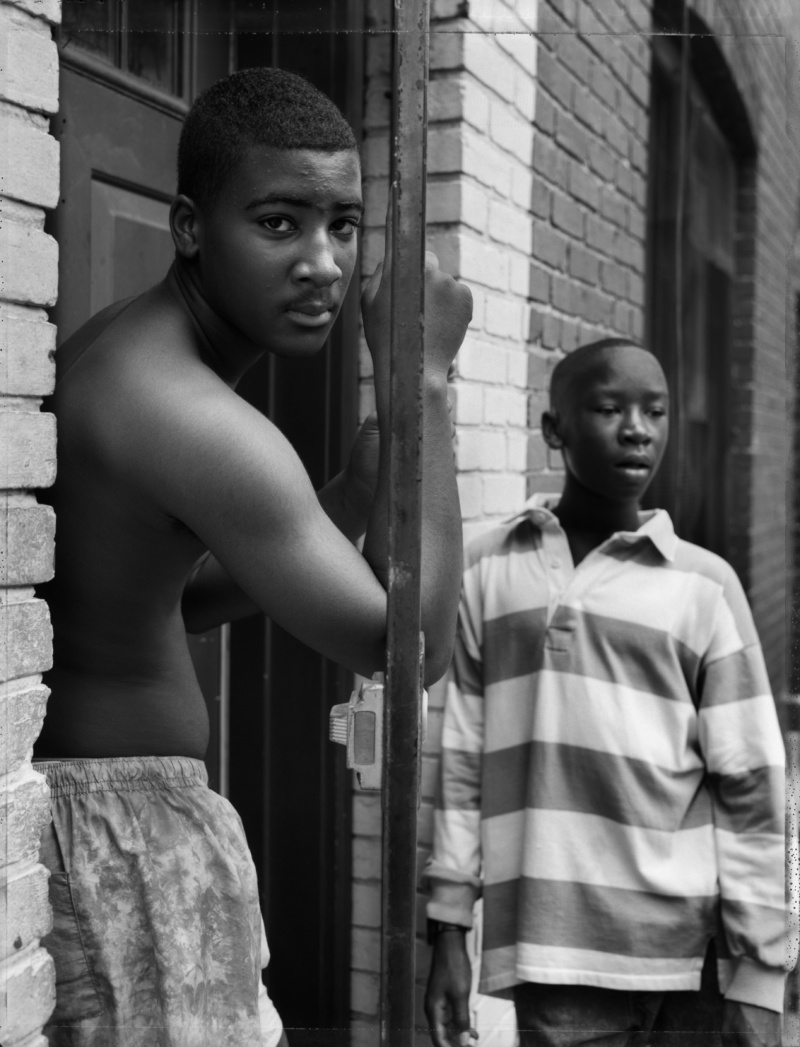

VC: After that, there was The Birmingham Project from 2012, which I personally think is one of your most powerful bodies of work yet.

DB: While I was making that work—which is about the six young African Americans killed on September 15th, 1963—Trayvon Martin was killed in Florida. It was a reminder, if one was needed, that the past is very much the present. In addition to the four girls who were killed in the dynamiting of the 16th Street Baptist Church that Sunday, two young boys were killed as well. One was shot in the back by a police officer in the disturbances that broke out after the bombing. The other, while riding his bike, was killed by two white teenagers after they left a pep rally that celebrated the bombing. The Birmingham Project initiated what has become an ongoing history project, in which I am looking at ways to make the African American past resonate in the contemporary moment.

VC: More recently, you turned your lens towards landscapes, whether it be urban sites around Harlem or pastoral settings situated along the Underground Railroad. Are there shifts in the way that you approach photography when you shoot landscapes as opposed to human subjects?

DB: Portraits and landscapes are very different ways of thinking about narrative within a photograph. I’ve always been highly conscious of the spaces that my portrait subjects occupied, so place has always been a kind of undercurrent in my work—as a part of narrative that contextualized individuals and situated them in the world. Night Coming Tenderly, Black, the Underground Railroad series, was created from the imagined vantage point of a fugitive African American escaping slavery and moving though that landscape. For me, the human presence has not disappeared entirely from my photographs. They’re just not in front of the camera.

VC: This brings me back to the present: “An American Project,” which is your most expansive retrospective yet. Is there anything that became newly clear to you, upon seeing over four decades of work displayed under one roof?

DB: The thing that I probably think most about, when I look at the exhibition, is how well those early photographs from the 1970s have held up. I was 21 or 22 years old when I started that work, and hadn’t been to art school yet. I’m pleased to still really like looking at them, 46 years later.

The retrospective is an interesting thing. Most artists are always looking forward to the work to come; I know I am. It kind of forces you to stop momentarily and take stock. My work is very much an ongoing American project.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?