When June Canedo de Souza was invited to photograph the twenty-one women whose portraits would comprise the new book Diža’ No’ole, Palabra Mujer (A Woman’s Word), her creative challenge was not how best to capture each individual but, rather, how not to. The women whose pictures she would be taking were undocumented Indigenous migrants hailing from regions across modern-day Mexico and Guatemala, including Villa Alta, Sierra Mixe and the Yucatán, as well as cities such as Ciudad de Oaxaca, Quetzaltenango and Huehuetenango. The book had been envisioned by CIELO, a non-profit organization serving Los Angeles’s Indigenous community, and, due to the sitters’ immigration status, it was imperative that their identifiable features be obscured. Undeterred, the photographer ingeniously translated this restraint into poetic, insinuating gestures and strategic framing—arms lift to block eyes from the sun, faces are cropped and subjects look towards one another in moments of shared laughter.

So seamless is this treatment that the uninformed viewer might not immediately notice it. Instead, the reader’s attention stays with the glimmering textures of the women’s ornate garments, carefully juxtaposed with individual testimonies that present their words in formats as varied as their attire. These fragments of text range in content from original poems and sensory memories of hometowns to clipped, biting revelations about life during the pandemic—the upheaval from which this book emerged.

Canedo de Souza had just relocated from New York City to Los Angeles a few months prior to the onset of COVID-19; among the few people she met before LA went into lockdown was Odilia Romero. It was a fortuitous encounter—Canedo de Souza had stopped to buy a meal from Romero’s husband, Poncho, a beloved community chef who was selling tamales out of their home in South Central. Pausing to chat, she learned of Romero’s lifetime of work as a Zapotec interpreter and organizer, and about CIELO—Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo—which Romero cofounded six years ago with fellow activist and cultural worker Janet Martinez.

In the months that followed their meeting, the pandemic left thousands of undocumented Indigenous people, many of whom were already far from their families, without employment or a safety net. Financial turmoil, in addition to the social and legal isolation inherent to undocumented status, were exasperated by the constant threat of contracting the virus. In the words of one of the women photographed for Diža’ No’ole, Palabra Mujer, “Before, the fear was deportation, and now, for many of us, the fear is getting infected, especially if we don’t have family around.” To respond to this dire need, CIELO set up the Undocu-Indigenous Fund, which sourced and made available 1.5 million dollars in community aid. The process of distributing this cash, much of which was allocated to the particularly vulnerable subset of women and single mothers, prompted in Romero and Martinez an impulse to communicate these typically unrecorded experiences in a way that would resonate with a wider audience.

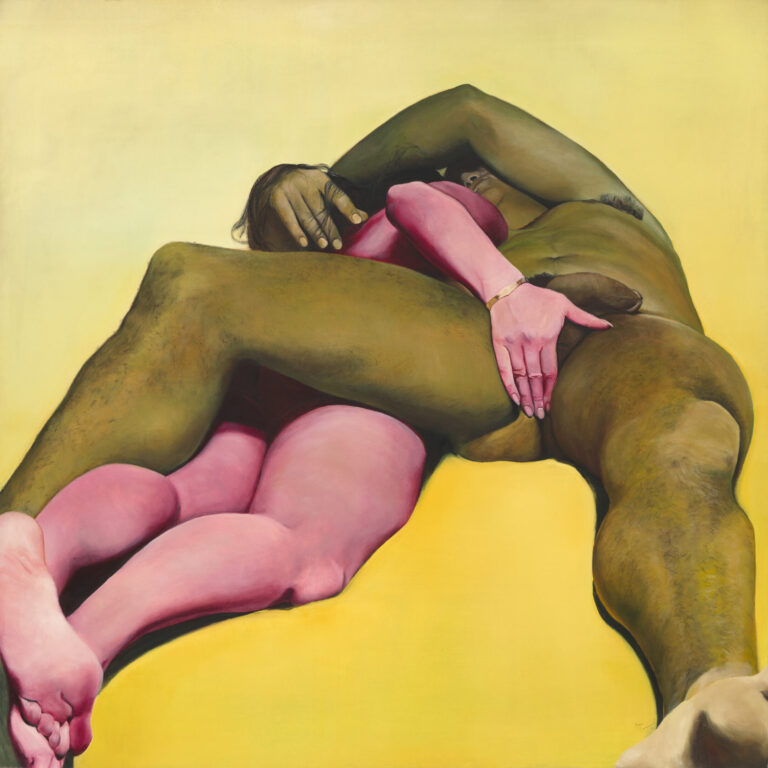

Visibility, however, is a fraught paradox, and the urge to share these women’s stories was coupled with the necessity to resist the voyeuristic aspects of forced legibility and the usual documentarian expectation to gain full access to subjects’ identities and lives. Privacy, itself a commodity and marker of privilege, is a matter of life and death for undocumented people. How could a book give these women prominence and agency—the productive, humanizing dimensions of visibility—without exposing them in ways that could be detrimental?

The project first took shape as an interactive digital map, developed in collaboration with the University of California, Los Angeles and designed simply to visualize the existence of multitude Indigenous identities within the city. “People lump everyone south of the border into Latinx,” Romero explains via Zoom, “but Mexico has sixty-eight Indigenous nations. Not everyone speaks Spanish. Oversimplified ethnicity narratives actually have deathly consequences for Indigenous communities who are migrating and therefore cannot be perceived or counted in ways that affect their livelihoods.” CIELO’s choice to refer to its community as undocumented and Indigenous—rather than undocumented in relation to a contemporary, state-mandated ethnonationality—resists a type of bureaucratic erasure that has been baked into the logistics of colonization for centuries, while also illuminating the profound inhumanity (and absurdity) fundamental in any attempt to make Indigeneity “legal.”

Though the subjects of Diža’ No’ole, Palabra Mujer were not able to reveal their individual identities, their traditional dress—which their new lives rarely occasion the opportunity to wear, and whose design traditions are often grossly appropriated—conveys heritage through regional style. The secret language of aesthetics latent in these fabrics, patterns and hues exemplifies how Canedo de Souza’s images override certain barriers to communication with messages encrypted for the careful eye. Even the soft pink textured stucco of the book’s cover is a photograph of the outside of Romero’s home, where many of the portraits were taken. “This book is a visual entry point into many larger, intersecting conversations about identity, community and home—subjects that themselves move continuously throughout the social sphere,” Canedo de Souza says on our call, adding that the project marks the beginning of what she hopes will be a longer-term collaboration. “That is why I like the format of a book. It’s an object that also migrates.”

Intent on honoring the subjectivity of their participants, it was imperative to Romero and Martinez that the book’s written components be first person anecdotes, sometimes appearing untranslated in pre-Columbian languages such as Zapotec and Mixtec. The indefinite physical and emotional rift intrinsic to the experience of migration is what the women in Diža’ No’ole, Palabra Mujer share, but are rarely able to communicate. “Care work is cultural preservation, and women and mothers are the people who do it,” Canedo de Souza explains. “Care work is the reason for a lot migration in the first place.” Many had no choice but to leave their children behind in order to come to the United States, a decision sometimes as difficult for their loved ones to understand as it is for them to carry. “We don’t always appreciate the sacrifices our parents make for us—the way women give their lives for their kids,” Romero adds. “This book is a place for them to voice that. That is also why we wanted to focus on memories such as our regalia and our food—the parts of our lives that are happy.”

When Romero and Martinez first approached their participants with broad, open-ended prompts to test what they might feel comfortable speaking about, their questions were met with silence; this, Martinez remarks, “was itself indicative of everything kept underneath the surface, of everything left unsaid,” and of the impossibility of expressing the cumulative effects of separation, disassociation, longing and loss. That silence, and the omission it contains, is made visible throughout the book in the deliberate use of blank space. Graphic absence reveals that, even in the presence of such potent testimonies, only through reading between the lines can one begin to grasp how much is missing—an immeasurable volume of these women’s work and of their lost history, the full scope of which could never be fully captured or explained.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?