Ian James, “Harmony of the Noosphere” at Five Car Garage It’s all static on 89.5 FM until you get within a few blocks of Five Car Garage. There, the crackle gently gives way to a groovy kind of drone—Welcome to the Noosphere. Drawing on the writings of New Age theorist José Argüelles, Ian James presents the Noosphere as an enveloping evolutionary intelligence sprouting collectively from us and our technologies, like some great planetary head of hair. The centerpiece of the show, KHLZ: The Rainbow Bridge (2020), is a suite of three pyramidal sculptures covered in Calacatta marble laminate, housing a radio transmitter that broadcasts those low-frequency vibes. The sculptures sit somewhere between cold, hard design objects and stagey Sci-Fi set pieces. Their sharp-edged solidity juxtaposes the formlessness of the drone. Likewise, the show’s deadpan stock-photo-esque imagery of people happily using electronics contrasts its vibe-y New Age graphics in a way that rocks its intention back and forth between earnest longing and something a bit more biting. It could be paradise but it was only Santa Monica.

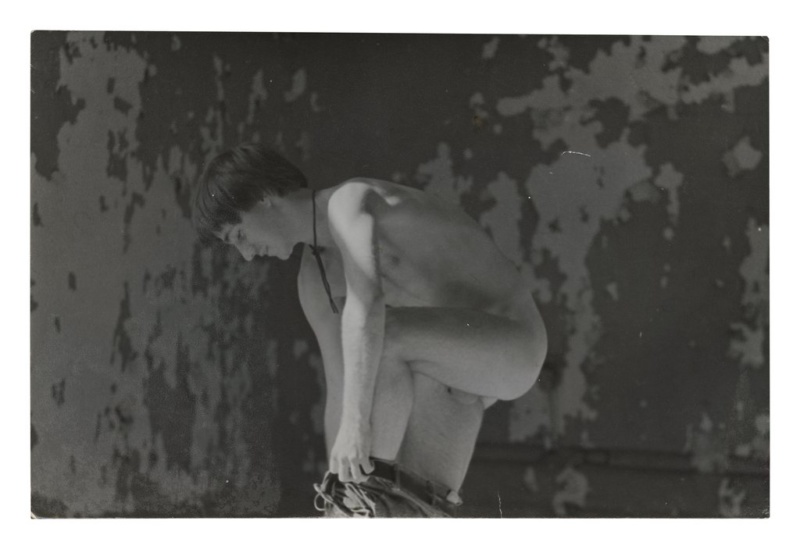

Alvin Baltrop at Hannah Hoffman Alvin Baltrop’s poetic documentation of cruising at the West Side piers, a now canonical image of 1970s gay New York, oozes inevitable pathos. You can feel it before you walk through the door. These are distant impressions of a bygone world: a community before it was ravaged by AIDS, a city before it was turned into a giant ATM and the piers before anyone would have thought to turn them into a sports and entertainment complex. We had to make our own sports and entertainment, the old-timers say. The exquisite photos are given a bit of extra aura by their timeworn surfaces. For Baltrop the piers were both stage and subject, and he had a great eye for the interplay of opposites: inside and out, shadow and light, peeping and participating, the decaying of the piers and the vitality of the blowjob.

Mayo Thompson, “Oily Works” at Gaga & Reena Spaulings The title pegs it: Mayo Thompson, who has never shied away from moving on to something new, is—as the press release informs us—“working now with oils on linen.” Thompson’s bio reads like a timeline of cool stuff to have been involved with over the past five decades, making him a sort of transatlantic Zelig of (sometimes not-so) underground culture. In Houston in the 1960s he founded the avant-psych band The Red Crayola; in London in the 1970s he was a member of conceptual art group Art & Language and then produced records for the Raincoats, the Fall, Kleenex and Cabaret Voltaire. His list of collaborators—from Pere Ubu to Derek Jarman to Moebius and Plank—is almost gratuitous. So, what of these paintings? They are eccentric and charming. There’s a massive one depicting a vintage Jaguar by the sea (Uh-Oh, 2020), and a few smaller ones featuring details extracted from famous works by Johannes Vermeer, Leonardo Da Vinci and the like. Here and there, a frog, a dragonfly, a house fly. They can be hard to get a firm grasp on but are nevertheless delightful—in a word, oily.

Patricia Fernández, “Heartbeats” at Commonwealth and Council The obsessiveness of Patricia Fernández’s show really sinks in by the time you get to the third room of handmade clocks carved of wood. There must be dozens of these variations on a theme, all rectangular, and embellished with medallions of tin, copper, ceramic tile and still more wood. The carving is often meticulous and sometimes ornate, which plays off of some of the more rough-hewn elements. Joining the clocks is a series of paintings featuring arrangements of skinny, crooked forms, like runes or ancient tools, in pale earth tones and blushes of turquoise and Easter blue. Their titles are specific latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates, while each clock takes its name from a type of moon in an esoteric calendar and the Gregorian month of its appearance (e.g. Crystal Moon in June 2020). These contrasting modes of measurement seem aimed at playing up the tension between the measurable and immeasurable, an effect amplified by the fact that none of the clocks are set to the same time. And none, as far as I noticed, matched the time on my phone, although one had a second hand with a fluttering little tic.

Lauren Satlowski, “Watch the Bouncing Ball” at Bel Ami Lauren Satlowski’s hyperreal still lifes fall within the neo-neo-surrealist tendency in painting you see around these days, cogitating on the mesmeric uncertainty of surfaces. There’s a holographic Santa sticker (Bad Santa, 2020) and some flowers plunged into a Ziploc bag full of clear fluid with shimmering sock and buskin stickers. A couple paintings star empty glass picture frames: one is adorned by a sticker that says “Help;” the other displays a patch that says, “Me worry?” Here, an uneasy mood prevails, dramatized in the preponderance of shadow: Santa’s face is obscured in gloom and both of the picture frames cast elaborate shade patterns in their wake. Satlowski painted all of these from life, setting up tableau in her studio, so even the weird humanoid figures turn out to be porcelain dolls. Hers is a depthless world, where people are things and things are images and shadows may be the only respite.

Oliver Payne and Kevin Bouton-Scott, “Sound of the Zeekers” at Overduin & Co. In 2019 Oliver Payne and Kevin Bouton-Scott made a video essay, The Art of Warez, which examined the mind-boggling and largely unknown history of ANSI art, primitive and sublime computer imagery painstakingly crafted out of a tiny set of letters, numbers and symbols from back in the bulletin-board prehistory of the internet. This show, which takes its title from a 1991 Leaders of the New School song, plays as a kind of sequel to the film, the two artists tracking some of its echoes down through the years. Bouton-Scott, who was a member of ANSI crew in the early ’90s, makes generally large paintings of generally appropriated imagery, sometimes in a collaged style reminiscent of Michel Majerus. Though they blare from a distance, up close they reveal their surfaces to be heavily worked or distressed. His source material can be pop cultural or drawn from more obscure quarters, in a way that suggests the cross-pollination between the two. For example, in Welcome Back (2020) we see an early ’90s T-shirt from the hacker group Legion of Doom, who took their name from DC Comics supervillains. The work seems to call across the room towards Suicide Squad (2020), a monumental depiction of a meme defending the honor of the eponymous and much-maligned 2016 DC supervillain blockbuster. Payne provides prints with ecstatic colors and ecstatic proclamations and a sculpture (Climbing Sculpture for 3 Rocks) where a neon orange climbing rope passes through carabiners, from rock to rock to rock atop pedestals, like an embodiment of the above historical cultural linkages. The spine of the exhibition is his Decades (2020), a series of brightly-colored silkscreen prints, vertically installed, that enumerate the titular decades like a roll call of empty signifiers: 80s, 90s, 00s, 10s, 20s…

in your life?

in your life?