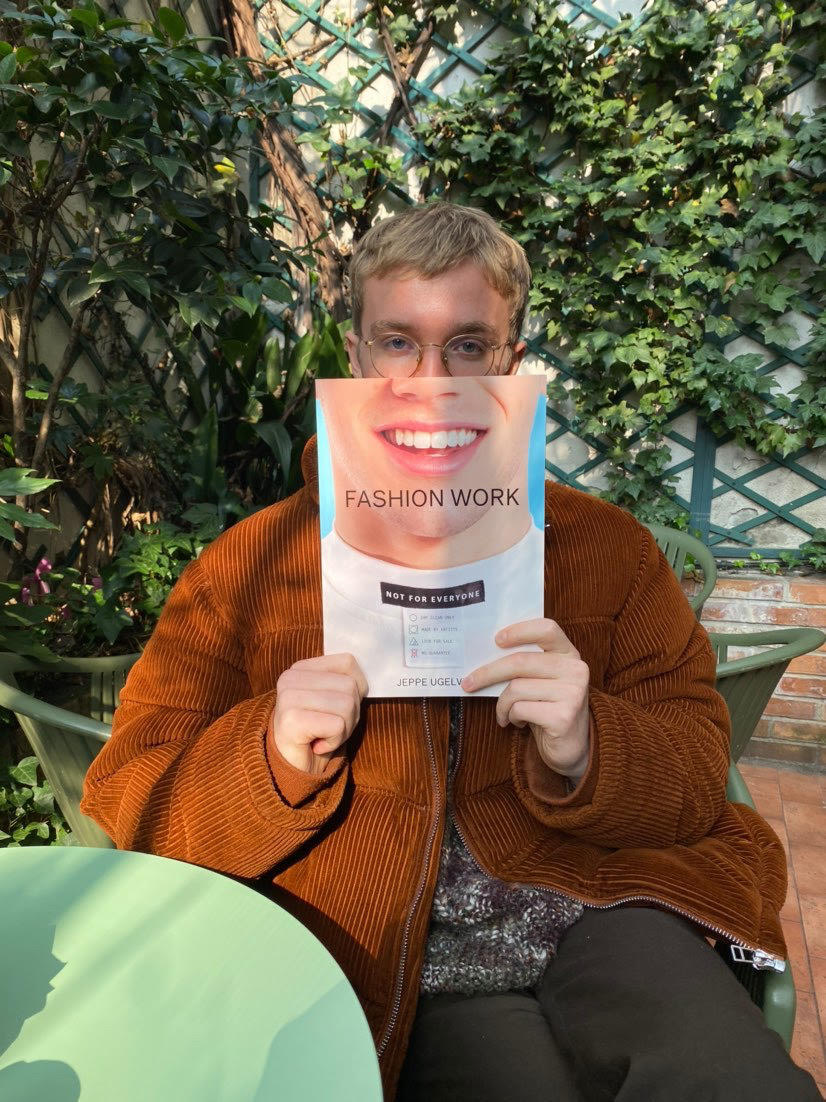

Jeppe Ugelvig, Independent Curator, New York and London In his first book, Fashion Work, released this spring by the Italian publisher Damiani, Jeppe Ugelvig orbits the twenty-five-year chunk of myth where experimental entities like Bernadette Corporation, BLESS and DIS threw lines between art and fashion, roiling the increasingly corporate infrastructures that undergird both worlds with new models for creative and cultural assembly. Ugelvig’s writing is confident, meticulous and playful. He submits the genre-defying brands who trafficked in transitory interventions to an academic rigor that, unlike so much of the art historical work done today, doesn't seal off the excitement of the era, but teases it out to make it newly accessible.

The book, which expands on an exhibition Ugelvig curated in 2018 at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard while finishing his MA at the school’s Center for Curatorial Studies, cobbles together previously unseen archival images and ephemera into a scrapbook for the utopian moment when DIY and collaborative practices were able to surmount fashion’s byzantine systems of production and circulation.

But neither the exhibition nor its accompanying tome read as memorials, at least in the obvious sense; instead, they are toolkits, intended just as much to dissect and enshrine the experimental strategies of these labels as to open up possibilities to a new generation of fashion workers for whom their radical work risks being relegated to aesthetic influence, as the increasing pressure of capital on art and fashion forecloses the strange space such brands invented and occupied. In the two years between the exhibition and the book, the prolific independent curator and critic was also a curatorial resident at Delfina Foundation in London and the Sandretto Re Rebaudengo Foundation in Turin, where he collaborated with fellow residents on an exhibition inspired by the region’s electronic dance music cultures.

Zoé Whitley, Director, Chisenhale Gallery, London When recounting her path to becoming a curator, Zoé Whitley, who grew up between Los Angeles and Washington DC, often fondly recalls formative trips she made to the Getty Villa as a teenager. Unlike many of the spaces in which we encounter contemporary art, whose overwhelming tidiness and silencing sterilization is frequently the subject of critique, the Getty Villa situates its collection in a near facsimile of domestic space and, in doing so, sets up a place for contemplation and dialogue where art and life are shown to be inextricably bound up with each other. Throughout her fêted career, Whitley’s exhibitions have made this case over and over again, with impressive force and new vitality. In 2017, Whitley co-organized “The Soul of Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” at the Tate Modern, which went on to travel extensively and is still touring today. The landmark exhibition portrays the art of the civil rights era not simply as an index of revolutionary political projects or desires, but as a revolution in and of itself. Ten years earlier, Whitley staged “Uncomfortable Truths” at the Victoria and Albert Museum; marking the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in the British empire, the exhibition disinterred art patronage’s ongoing indebtedness to profits made through slavery.

Contemporary art is often made out to be insular and irrelevant, mattering little to anyone outside of it, and the community itself is likely guilty of buying into this myth, perhaps more than anyone. But Whitley has made a practice out of refusing that narrative and repudiating the conditions of inaccessibility that perpetuate it. Whitley wrote her doctoral dissertation on representations of Blackness in the fashion magazine Vogue; she is fiercely academic yet deeply devoted to the everyday, and to the idea that through it we can read the texture of the larger forces that shape it. After curating Cathy Wilkes’s much acclaimed presentation for the 2019 Venice Biennale, and less than a year into a new post at the Hayward Gallery, Whitley is already on the move as the newly-appointed director of London’s Chisenhale Gallery, where she will have the opportunity to collaborate with living artists on major solo commissions.

Qu Chang, Curator, Para Site, Hong Kong Qu Chang moved to Hong Kong four years ago to become the associate curator of Para Site. This August, she will leave the non-profit to pursue her PhD. Her thesis isn’t yet fully fleshed out, but its premise takes what she’s done at Para Site to the next logical extreme: “I want to look at the contemporary Chinese art scene through the lens of emotion,” she simpers cheekily. “I want to look at the structure of feelings. It will make more sense when I get started.”

We don’t doubt it. In her short tenure, Qu has made a name for herself putting on exhibitions that delight with their emotional heft. Take, for example, her attention catching 2018 show, “Crush,” which centered on heartbreak. “The starting point is always something intuitive, something from life,” she says of her curatorial process. “My first, very brief impressions of Hong Kong were that the art here tends to take personal and private matters as its starting point. When you talk to an artist, the first thing they tell you is about their family or something from their life. “Crush” was my attempt to get closer to all those working in Hong Kong, while also tapping into my own obsession with romance, especially the narrative of unrequited love.” Qu embraces complexities—even her own—which is why I Love Dick was one touchpoint for “Crush,” and also why the exhibition ended up spinning out even further than Chris Kraus's doomed throuple. “You start talking about love and desire, and then you realize the ways that romance can mirror larger social phenomena such as nationalism and consumerism. Love is deployed everywhere, even for the packaging of commercial products.” “Window shopping,” for example, she describes as “the essence of our unrequited love affair with luxury.”

Emotional landscapes are a recurring theme across Qu’s work. “Hard Cream,” her solo show with artist Doreen Chan, also centered around a breakup. The exhibition itself consisted of a series of performances and gestures that revisited the dwelling once inhabited by the artist and her ex, and the rituals they shared there. “There were traces of movements that convey those memories without necessarily producing them,” Qu explains. “I'm never looking to take the straightforward path—I thrive in inviting the complexities.”

Introspection is part of this vision; Qu’s discoveries are not always external. “I need to work with people who I can empathize with,” she says. “It’s hard for me to work with an artist I haven’t spent time with; I need to really understand who they are and what motivates them to do the work in the way that they do, in order to even be able to write about them. For me, art is a personal choice. I enjoy working with people who I like (though who doesn’t, haha) because the mutual vibrations tend to evoke a strong sense of empathy and thus more inspiration, in an unexpected way.”

Ryan Dennis, Chief Curator, Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson Ryan Dennis is still living out of boxes at her new loft in Jackson, Mississippi when we speak on the phone; she describes her window view as “verdant”—an escape that reminds her of her hometown, Houston. The curator arrived last week, with her partner in tow, after a pandemic-delayed start to her new position as chief curator at the Mississippi Museum of Art, following an almost decade-long run at the helm of her native city’s Project Row Houses, a nonprofit arts space whose national profile was heightened thanks to her community-oriented approach and prescient, responsive programming.

Her first agenda item for her new role? A listening tour. “I want to find ways to embed deep listening into programming—this isn’t exclusive to my work in Project Row Houses, but rather my entire curatorial outlook,” she says. At Project Row Houses, Dennis embraced a flexible definition of culture, making room for different kinds of creativity to mingle under the spaces of one roof (read: a handful). In Mississippi, she looks forward to slowing down and being more strategic, thanks to the inherently more relaxed pace of a smaller city and a larger institution. “I want to create programming that is meaningful and adds a thread or a thought to the conversation that wasn’t articulated before, because no one was listening to the silences,” she explains.

Dennis’s own trajectory into curatorial studies happened at such a juncture. Studying art history at the University of Houston, she found herself intensely frustrated by a syllabus totally devoid of Black artists. “I knew there were Black folks making art,” she says. “I felt compelled to be part of putting those narratives into the mainstream. The same is true today. I’m interested in bringing Black narratives into the museum that aren't necessarily just related to trauma, but also to Black joy and Black optimism.”

Constructing multiple entry points for public engagement while and elevating unsung narratives also play a central role in Dennis’s upcoming Texas Biennial, which she is co-curating alongside Evan Garza. Now slated for 2021, the open-call exhibition has typically happened in Austin, but Dennis and Garza are hoping to add site-specific commissions to this edition, as well as spaces in Houston that serve diverse communities.

Now, Dennis is focused on settling in and figuring out how her first fall in Mississippi will work under the conditions of COVID. She is bringing Leonardo Drew’s 2019 project, City in the Grass, originally commissioned for Madison Square Park Conservancy, to a public greenspace—a gesture that will enable the museum to begin physically reaching back out to the community as it tests its in-gallery exhibition capacities.

Nellie Killian, Independent Curator, New York When Nellie Killian put together “Tell Me: Women Filmmakers, Women's Stories” for The Metrograph theater in New York this February, she didn’t expect the film program to be revived a couple of months later. We are incredibly thankful that the curator adapted her work so quickly for Criterion Collection’s streaming service, providing us with some much-needed quarantine content.

Our entry point was Leilah Weinraub's Shakedown, but we stayed for Barbara Hammer’s Audience, and then a right turn for a double feature of Susana Aiken and Carlos Aparicio (The Salt Mines and The Transformation) before driving straight on through the supplementary materials, including an interview between Killian and her former college roommate, comedian and actor Jenny Slate. In this conversation, Killian tease out her thesis: a scathing counterpoint to the narrative accidently popularized by the #MeToo movement, according to which women have not shared their stories out of fear. Pulling on examples as early as 1970, Kilian’s asserts that it is not through lack of will that female filmmakers have remained on the periphery, but rather a critical differential in funding, media attention and mass distribution. “Listening to women doesn’t mean just listening to them tell sad stories,” she says. “If people aren’t willing to listen to women talk about their weekends, why would [women] think there was space for a more serious conversation.

Killian cut her teeth at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where she helped shape the program for many years and cofounded Migrating Forms, an annual week-long film festival, in 2009. Designed to step away from the idea of independent film, Migrating Forms spun off of the New York Underground Film Festival—imagine Neil Beloufa, GCC, Frances Stark and Seth Price all occupying the same playlist. Over the course of its decade in action, the festival’s experimental attitude left an indelible mark on the city’s scene as an electrifying bridge between the white cube, independent cinema and emerging media communities.

What Killian misses about film during quarantine is the movie-going experience; she takes pleasure in creating moments of discovery and views education as a symbiotic process. “I learn so much from watching movies with other people,” she says. “I miss the texture it adds to the work.” For now, though, her thoughts are digitally-minded. “Translating programs to streaming services provides an interesting process,” Killian admits, noting that there are unexpected upsides. “I've been pleasantly surprised to see so many people reacting to short and mid-length films in the “Tell Me” series. There is a huge appetite for things that don’t require a feature-length time to watch. I think you get used to programming shorts in programs, or before features, and you think about how the program works as a whole. It’s good to be reminded that these pieces stand on their own.”

Maurin Dietrich, Director, Kunstverein München, Munich In 2019, Maurin Dietrich was named director of the Kunstverein München, following four years at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Her first year at the helm saw major exhibitions of the work of Diamond Stingily and Pati Hill, and the launch of a writers’ residency in cooperation with the city of Munich. Both shows represented significant firsts for the artist, in Stingily’s case her first institutional show in Europe and, in Hill’s, the first comprehensive presentation of her work to be mounted after her death. And while neither artist is by any means unknown, their practices—which spill out of art and into fiction and poetry—tend to resist the exhibition format. The shows, both of which Dietrich curated, are testaments to her enduring commitment and sensitivity to agility and invention in art, setting the standards of display for difficult works that engage with social, political and historical contestations in profound ways. While working at the KW and lecturing at the University of Arts in Berlin, Dietrich also co-founded the experimental space FRAGILE, with Jonas Wendelin, where the duo have hosted equally ambitious projects by similarly difficult to define artists, among them the musician SOPHIE, writer, artist and publisher Kandis Williams and artist and hostess DeSe Escobar.

Maurin Dietrich, Director, Kunstverein München, Munich In 2019, Maurin Dietrich was named director of the Kunstverein München, following four years at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Her first year at the helm saw major exhibitions of the work of Diamond Stingily and Pati Hill, and the launch of a writers’ residency in cooperation with the city of Munich. Both shows represented significant firsts for the artist, in Stingily’s case her first institutional show in Europe and, in Hill’s, the first comprehensive presentation of her work to be mounted after her death. And while neither artist is by any means unknown, their practices—which spill out of art and into fiction and poetry—tend to resist the exhibition format. The shows, both of which Dietrich curated, are testaments to her enduring commitment and sensitivity to agility and invention in art, setting the standards of display for difficult works that engage with social, political and historical contestations in profound ways. While working at the KW and lecturing at the University of Arts in Berlin, Dietrich also co-founded the experimental space FRAGILE, with Jonas Wendelin, where the duo have hosted equally ambitious projects by similarly difficult to define artists, among them the musician SOPHIE, writer, artist and publisher Kandis Williams and artist and hostess DeSe Escobar.

For a museum now almost two centuries old that still strives to respond and contribute to the contemporary conversation with the speed and relevance of a project space, Dietrich’s assiduous attention to unwieldy multidisciplinary experimentation foreshadows an exciting new direction for the institution, which, despite (or perhaps because of) its small size, has consistently succeeded in presenting exhibitions on the forefront of international developments while simultaneously irrigating Munich’s own cultural landscape. Indeed, Dietrich imagines the Kunstverein’s fledgling writers’ residency not as an expansion of its curatorial mission, but as a central and indispensable component of an expanded notion of curation, citing the word’s Latin root, “curare”—meaning to care for or look after—“which extends to people and the hospitality towards them.”  Tandazani Dhlakama, Assistant Curator, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town In the wake of former Zimbabwean prime minister Robert Mugabe’s contentious resignation, Tandazani Dhlakama staged an exhibition at the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town titled “Five Bhobh: Painting at the End of an Era” that brought together 29 local artists whose work engages the country’s precarious political circumstances. The fare for an average ride on a kombi in Zimbabwe is five bhobh. Kombis are minibuses or vans that function as a main mode of transportation in many African cities, where passengers from all walks of life encounter each other in cramped quarters, perhaps united by a shared angst or anxiety about the journey at hand. Dhlakama’s exhibition proposes the space of the kombi as a metaphor for the country’s current situation of transit, where political change is undertaken not without discomfort and difficulty. Further, Dhlakama hones in on the kinds of conversations that take place on the kombi, as blunt discussions about the government must be cloaked in metaphors and figurative imagery. She reimagines the artist not as a “catalyst” for social change, as so much of discourse around contemporary art demands, but as an interpreter of it—its exegete, whose task is not just to fashion the coded images that allow political disclosures to be made, but through their inventive beauty, make moments of revolution, failure and change themselves more bearable.

Tandazani Dhlakama, Assistant Curator, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa, Cape Town In the wake of former Zimbabwean prime minister Robert Mugabe’s contentious resignation, Tandazani Dhlakama staged an exhibition at the Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town titled “Five Bhobh: Painting at the End of an Era” that brought together 29 local artists whose work engages the country’s precarious political circumstances. The fare for an average ride on a kombi in Zimbabwe is five bhobh. Kombis are minibuses or vans that function as a main mode of transportation in many African cities, where passengers from all walks of life encounter each other in cramped quarters, perhaps united by a shared angst or anxiety about the journey at hand. Dhlakama’s exhibition proposes the space of the kombi as a metaphor for the country’s current situation of transit, where political change is undertaken not without discomfort and difficulty. Further, Dhlakama hones in on the kinds of conversations that take place on the kombi, as blunt discussions about the government must be cloaked in metaphors and figurative imagery. She reimagines the artist not as a “catalyst” for social change, as so much of discourse around contemporary art demands, but as an interpreter of it—its exegete, whose task is not just to fashion the coded images that allow political disclosures to be made, but through their inventive beauty, make moments of revolution, failure and change themselves more bearable.

After the exhibition, Dhlakama, who had worked in the museum's education department for two years, was appointed to her current position as assistant curator. The Zeitz MOCAA is the largest museum in Africa, and the world’s largest museum of African art. It offers Dhlakama a new scale for realizing her curatorial visions, and she is certainly no stranger to the kinds of questions and concerns the institution seeks to confront. In her previous position at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, Dhlakama curated a similarly sprawling survey of 50 women artists entitled “Woman on Top,” to complicate unfolding conversations about gender. Her projects promise to continue to challenge, as she strives to do justice to the experiences of those living through moments of change.

Claude Adjil, Curator at Large (Live Programs), Serpentine Galleries & Curator and Producer at Young Turks Records, London Claude Adjil is a curator at large (of live programs in particular) at the Serpentine Galleries, where, in addition to commissioning and producing strange and exciting exhibitions—like Patrick Staff’s “On Venus,” which draped the building in a network of pipes flowing with acid or fashion designer Grace Wales Bonner’s “A Time for New Dreams,” a sweeping meditation on magic and mysticism—she looks after the museum’s park night program, for which she has collaborated with artists such as Marianna Simnett, Meriem Bennani and Carrie Mae Weems, along with musicians Klein and Yaeji. Somehow, Adjil also finds the time to work in music, as a curator and producer at the record label Young Turks, and is dedicated to realizing artist’s most challenging projects across disciplines.

Last year, in the Serpentine’s Junya Ishigami-designed architecture pavilion where park nights unfold each summer, septuagenarian Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña wove a temporary nest for the earth’s clit. The year prior, Adjil curated a Telfar Clemens’s presentation for which the fashion designer collaborated with the band FAKA on a performance that featured a choir. Her projects are at once monumental and intimate.

In an art world increasingly unconvinced by its own transformative potential, her straightforward foregrounding of the miraculous, the generous and the real is radical, as is her steadfast commitment to working not just with artists who transcend disciplines, but also to inviting creative individuals, like fashion designers or musicians who aren't visual artists at all, to make work in the museum, hopefully bringing with them untapped audiences. For Adjil, cross-pollination is as much a method as it is an ethic. She is now preparing a solo exhibition of the pioneering multi-hyphenate artist Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster.

Zoe Butt, Independent Curator & Artistic Director, The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre, Ho Chi Minh City “I can't live on just surface,” says Zoe Butt. “I can breathe there for a little while, as sometimes my job demands it, but if I am to maintain my curiosity I need to have time to dive deeply.” For Butt, this means setting two days per week aside for her own research—no an easy feat for a globetrotting curator, let alone the artistic director of Vietnam’s premiere contemporary art space.

Stacking her desk with international appointments, Zoe’s independent projects abroad, like the most recent Sharjah Biennial, provide inspirational fuel for her work locally. “One balances the other,” she says. “They are parts of the same whole.” At The Factory, her attentions are lavished on overseeing every tentacle of the multi-pronged institution. The country’s first purpose-built space for contemporary art, The Factory serves as an education, research and development hub for the region. As a result, the its ambitions have a circumambient quality. Exhibition-making is not the center of activity, but rather one avenue for engagement. This is especially key for an institution whose visual outputs are subject to government approval. “While censorship provides yet another obstacle when putting together a show, it is not the only reason that my efforts at The Factory are not primarily about exhibitions,” Butt explains. “I left the museum world because when I worked within them, I would find myself always returning to default models of ‘doing’, a consequence of university training and museum systems, rather than forging new ones. I had to ask myself what I could do as a curator; the answer was to create encounters for learning. For that, I’m not sure that exhibitions are a premium platform, at least not within the cultures I care the most."

One of The Factory’s primary occupations is figuring out how a contemporary art space should function. There are no rules here (with the exception of government oversight). “We don’t want to disengage with the Western canon, but we do want to create a different perspective—one that has its own priorities and languages,” Zoe says. “We want to decolonize our brains and create words that describe the things and histories that matter to us.” This means reaching out to neighbors vis-à-vis initiatives like Pollination, a residency program that gives pairs of Southeast Asian curators and artists the opportunity to work together on long term, multi-city projects. “If culture is to survive in this increasing authoritarian landscape, we need to accept the social limits of where we are and use this struggle to fuel us,” Butt says. “We need to challenge ourselves to find the boundaries of our agency—otherwise culture will die, becoming just a means for propaganda.”

Margot Norton, Curator, New Museum, New York After almost nine years at the New Museum, Margot Norton has left her mark, not only on the institution, but on the city. Hired by the New York kunsthalle first as an assistant, Norton was promoted to curator in 2017—an acknowledgment of her hard work, which included career-defining solo presentations for artists such as Laure Prouvost, Pia Camil, Chris Ofili, Sarah Charlesworth, Anri Sala and Pipilotti Rist. In looking back on her tenure, Norton revisited her first meeting at the museum, a team conversation over an informal lunch that she had over-prepared for. “I came in with so many notes and ideas—I wasn’t sure what to expect,” Norton says. “I was struck by how Massimiliano Gioni, our chief curator, responded to everyone’s ideas, and how much the program was thought about through bouncing ideas off each other informally and everyone weighing in.” The collaborative way in which the New Museum’s schedule is arrived at aligns closely with Norton’s own approach to exhibition-making. “There is a special sense of fluidity baked into an institution like New Museum that enables this kind of constant reevaluation,” Norton says. “As a curator, this gives you the power to respond.”

She traces her belief in this approach back to an early internship at Exit Art, an institution whose programs she attended as a teen. “Exit Art had a generous and interesting policy for creating exhibitions, where they would come up with a topic and theme and then share a proposal that anyone could apply to…the idea that an exhibition could develop from a single question and then weave together various voices, while remaining authentic to those authors, was eye-opening for me. And, that this could be an organic process stemming from real conversations between the artists and the staff left me inspired.”

Now, more than a decade later, this wide-net approach is serving the curator well as she tackles the New Museum’s upcoming triennial, alongside co-curator Jamillah James. “In our first conversation, we decided that instead of working backwards from a theme, we would let things evolve out of our studio visits, and those conversations drive the show,” says Norton. The exhibition is now almost two years underway and slated to open in late 2021. “I feel like we had already piloted the work-from-home reality of COVID with this show,” Norton jokes. “Being curators on opposite coasts, the idea of doing research and meeting with each other remotely was something we had to tackle early on in our process.” Norton is grateful for the year of physical research that she and James were allowed before being straddled with today’s fluctuating travel restrictions, but also for this moment of digestion; “Most people I’ve been speaking to are expressing angst and frustration about their lack of productivity at this moment, but I think it’s important that we reevaluate that idea of being productive.”

in your life?

in your life?