The word utopia comes from the Greek outopos, which translates to “no place”—not the bacchanalian land of ambrosia and French kissing that we associate with an idyllic otherworld, but instead the warm bath of nothingness. Though this is the term’s derivation, its pronunciation comes from eutopiā, which means “a good place.” This friction—the opposing wants of nothingness and goodness—is the motor for “Cruising Utopia,” photographer Peter Hujar’s digital exhibition at Pace Gallery. The photographs in “Cruising Utopia” luxuriate in this space of dual meaning. With many of the images taken in the post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS window, the photographs function like cartography, mapping the proximity of contradictory urges: our desire for pain is pushed right up against our desire for pleasure; our desire for cleanliness exists inches from our yearning for filth.

The image that most famously toes this line is Orgasmic Man, 1969—a photo of a young, clean-shaven man wincing in extremis, his face’s gnarled contortions not stemming from pain, as one might assume, but rather from an orgasm. (The image also notably serves as the cover of Hanya Yanigahara’s 2015 novel A Little Life.) If Shakespeare called the orgasm la petite mort—the little death—does it not serve to assume, then, that death is the big orgasm?

Perhaps a more interesting example is Paul Thek Masturbating, 1967, an image of the eponymous artist and Hujar’s long-time romantic partner (the two were referred to as Peter and Paul when coupled) nude and in a state of repose, his hand and penis just out of the frame. The dips in Thek’s sternum and the taught sinew of his slight frame almost turn the image into a landscape, recalling Hujar’s photographs of water—namely the Hudson River—in which deep blacks were burnt and bright highlights were dodged, resulting in intensely sculpted compositions. Of equal note is the way in which the image of Thek recalls his own Death of a Hippie self-portrait of the same year.

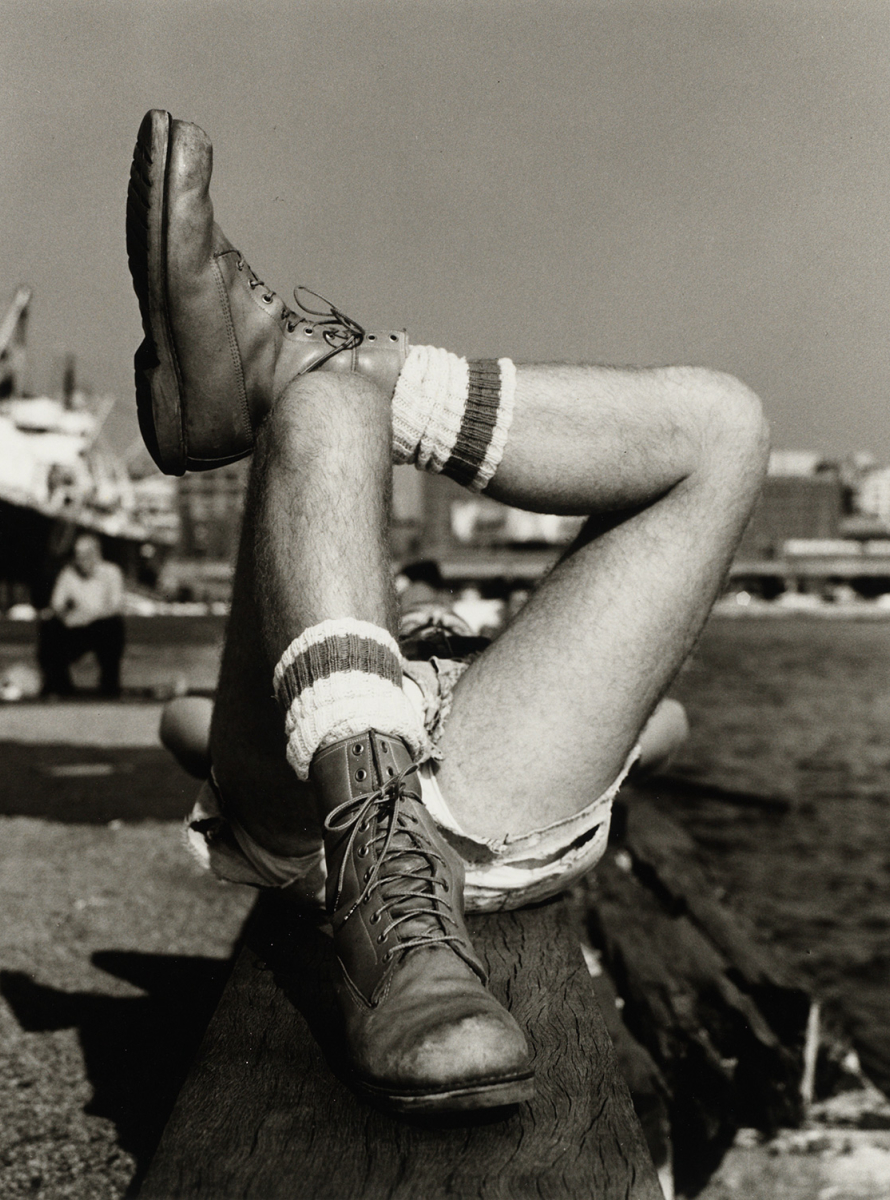

The exhibition opens with a suite of images from Manhattan’s West End, taken in the ’70s: photos of handsome men at the Christopher Street Pier, including one who looks to be a teen, buoying himself up on the ropes of a docked ship. These photographs measure the ebb and flow of the Hudson, and one of the westside’s long lost parking lots—in the distance, a sign reads “PARK HERE” and below it another, smaller sign: “LEATHER.”

in your life?

in your life?