Art is an opportunity to share, but what it shares is up to its maker. The interests of these seven creatives lie beyond the purely visual. Addressing topics that range from government surveillance to the historicization of colonialism, their work is activism—it challenges viewers to ponder, discuss and create change. As artist Sanford Biggers summed for Cultured in 2016: “My work is a platform. I am not trying to be overly didactic and instead take a nuanced and layered approach. One of those layers has to do with social justice and re-righting history.”

“When we want to talk about diversity, it’s not a binary—it’s intersectional,” said New York-based artist Elia Alba to Cultured in 2017. “There is diversity within diversity.” Her work shows the multifaceted and interconnected identities of people of color through photographs posed in different professions, intimate portraits and salon-style dinners that gather artists to talk politics over food. The goal is true inclusivity and breaking down barriers. “I felt like I was somewhat naïve as far as how people felt amongst each other,” Alba, who identifies as both Black and Latina, said of her first dinner in 2012. “I just thought there was stronger unity amongst folks of color, but I felt like there was somewhat of a divide. A divide that didn’t exist within me, clearly, but it existed outside of me, and I wanted to keep on probing that and continue with this conversation.”

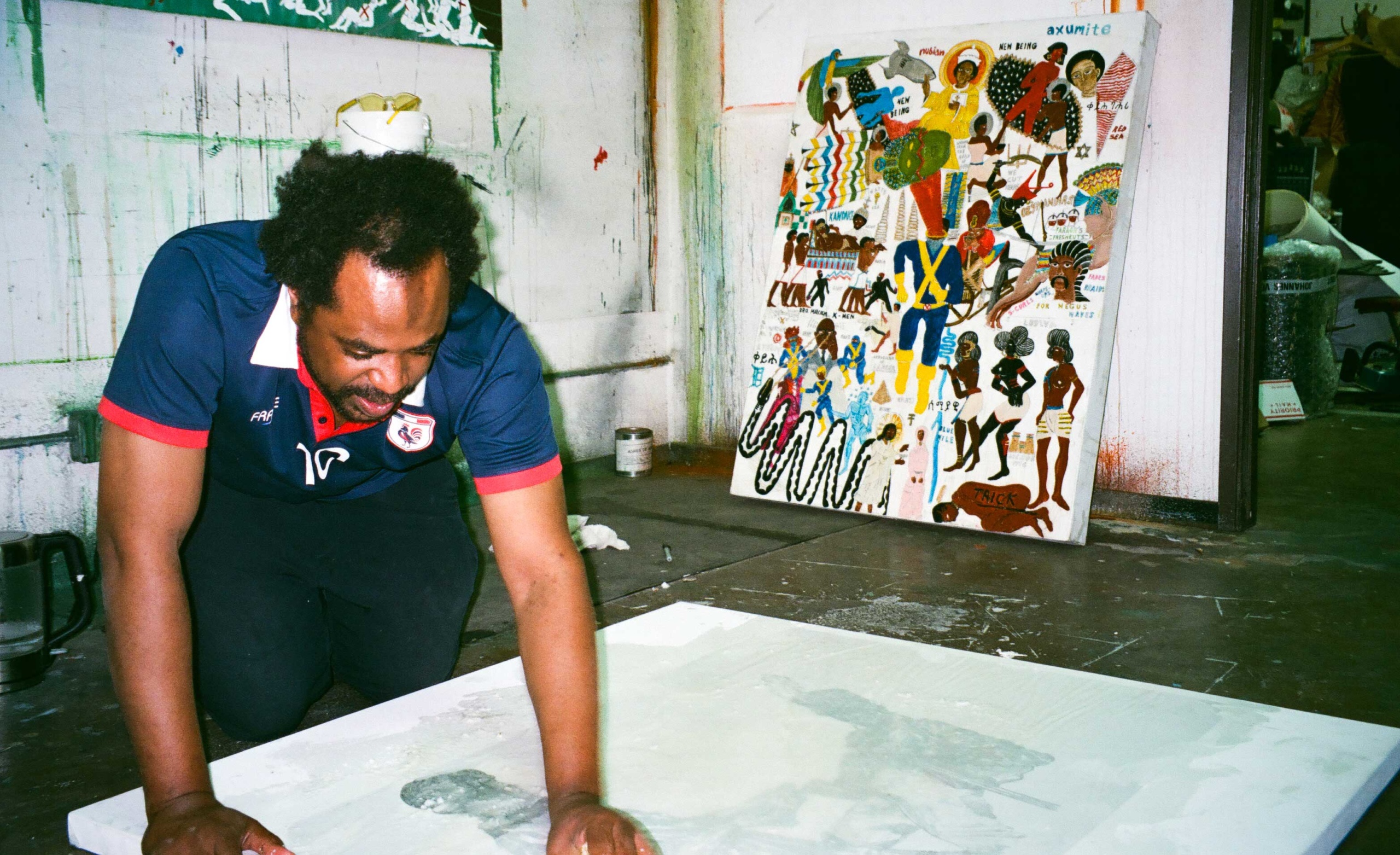

“The paintings of the Los Angeles-based artist, historian, poet and musician, also known as Frohawk TwoFeathers, reconfigure colonial and imperial histories. His characters walk the same earth we do, and are beholden to the same histories, but their reality is a hyper-saturated, detailed explosion of colonial reimagining that spans a multi-layered matrix of time and geography,” wrote Nevena Dzamonja for Cultured this year. Working through the limitations of history, Rashid investigates ideas of empire and uses his work to revise the stories that history books tell, which inherently contain a European colonial perspective. As Rashid says: “I’m sharing a history where I, as a Black man, and people who look like me, are included in this narrative as equals, and not just as the subservient mass that many historical publications describe.”

“The entirety of my career has been devoted to touching on aspects of African-American history and culture that aren’t necessarily well-known facts—instances that we don’t talk about because America is in a state of racial denial,” said artist Sanford Biggers to Cultured in 2016. Manipulating items vaguely associated with domesticity (quilts, decoupage fabrics, African figures covered in wax), his deceptively quiet, prescient work reveals the dark corners and complexity of African-American and American history such as police brutality and systematic racism—struggles that still persist today. As he explains: “The material I like the most is history, as opposed to any physical material.”

Artist, poet and teacher Sable Elyse Smith uses language to establish and destroy. For her artworks about mass incarceration, she focuses on the personal—her specific experience of visiting her own father in prison—through videos of her unconscious movements, a sculpture that references the wall murals she encountered at the six facilities between which he was transferred and photographs. “When people talk about prison, or mass incarceration, they are talking about statistics, they are talking about policy, they are talking about prison abolition, but they are not necessarily placing the more quiet interior narratives next to those things,” Smith said to Cultured in 2017. “I feel like there is a tendency for the conversation to be large and abstract, but not actually think about how all bodies function in that space and what the residue is.”

Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo)

Puppies Puppies (Jade Kuriki Olivo) uses their art in performance, installation and poetry to replace the impersonal with the personal, and to invite viewers to reexamine identity politics. Body Fluid (Blood), demonstrates that through presence, one can erode stigmas and create access to care. And their performance work Coffin draws from the death of their own father, who had stockpiled for a Y2K-type disaster that never came during his lifetime. “Anonymity and its tensions within a world structured by the hierarchies and languages of governments, institutions and corporations remerge over and over in Puppies’ work,” wrote Kat Herriman of the artist for Cultured this year. “They embody personal responsibility through their own participation in the work and what they ask of others.”

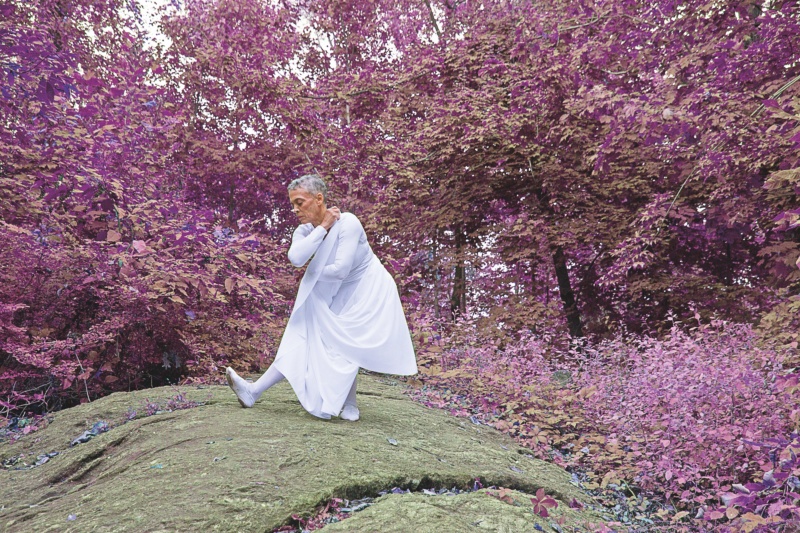

The first Black recipient of the Hugo Boss Prize, sculptor Simone Leigh’s work is dedicated to bringing Black femininity to the center of the narrative. “I’m interested in describing epistemologies or ontologies of Black women and femmes,” she told Cultured in 2019. While the world may seem to only just be catching up, the growing recognition of artists who are also women of color within institutions is in large part due to Leigh and her contemporaries’ direct and multifaceted engagement of race. “The more specific I get the more people I reach. And I’m so proud of my heritage,” says Leigh. “We have a Black renaissance afoot when it comes to art and scholarship in multiple fields. We are making the change.”

Much of artist Trevor Paglen’s work is revealing truths unseen: the government surveillance of private citizens, the dangers of technology’s constant invasions of privacy and the overreach of the state at large. “Paglen is worried about what happens when humans are taken out of the decision-making process, particularly in matters related to artificial intelligence and mass surveillance,” wrote Ted Loos for Cultured in 2018. But mostly Paglen is worried about who holds the power over our lives. “What forms of power do these systems amplify, and at whose expense?” he asks. “For me, that’s the larger thing I’m trying to get at.”

in your life?

in your life?