Angel Otero’s work is doubly known for its physicality, both in terms of its laborious production and complex textured surfaces. Yet the artist is hardly phased that his next show with Lehmann Maupin will be experienced virtually. The challenge, he explains to me (over the phone, of course) in the days leading up to a private group studio visit that the gallery organized via Zoom, is to envision an online encounter that is more than just an image or a rendering; how might it be something more intimate, immersive, personal?

For Otero, reinvention is nothing new. After a brief stint working in insurance sales, he moved to Chicago from his native Puerto Rico in 2003 on a scholarship to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He arrived in what seemed like a parallel universe, complete with its own ontology for what constitutes art—one that his work continues to grapple with and sometimes even to contest. Over the past decade, his paintings, which tend to be preceded by “process-based,” have been gestural and mostly abstract, inviting comparisons to such prophetic heavy hitters as Pierre Bonnard, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock, who he cites as inspiration. For Otero, like many artists before him, abstraction was an escape—from reference, from reality, from self. “Sometimes I feel like I hide behind my process,” he tells me with disarming candor in a conversation that felt less like an interview than two friends catching up. But, at the same time, Otero’s work never wandered as far from representation as a first glance might conclude. Typically discussed in relationship to memory, his bold, labyrinthine paintings contain a particular longing that keeps seeping through. The past always does.

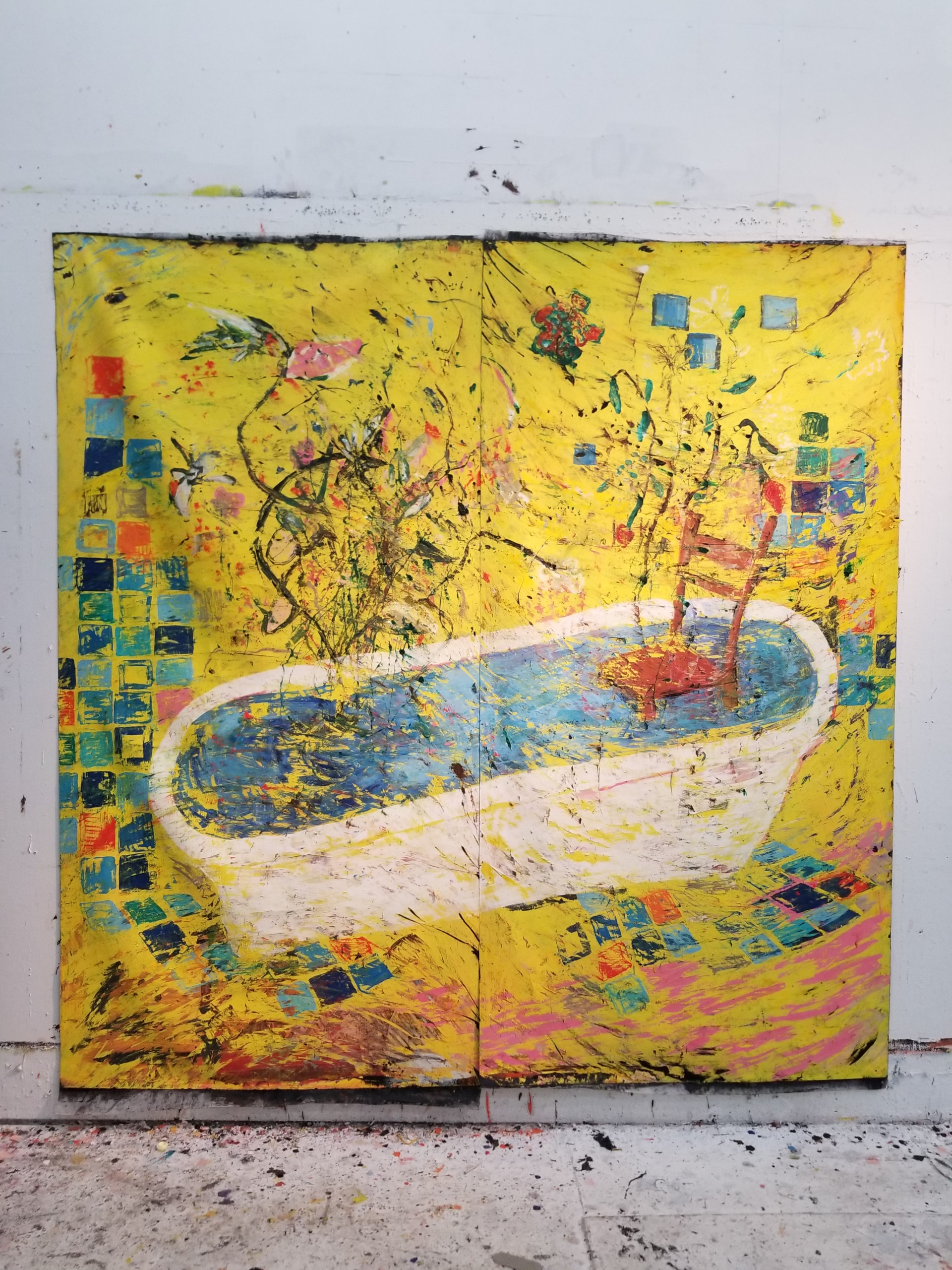

Almost exactly a year ago, Otero’s exhibition, “Milagros” (Spanish for “miracles”) opened at Lehmann Maupin in New York in real life. It debuted a series of what might most accurately be described as enormous tapestries, made from paint, that each hung free from the bar of a stretcher. The sheaths of paint themselves, previously coined “oil skins,” were already a signature of his practice, but the seeds for this presentational breakthrough had been planted almost two years prior, in his 2017 solo show at the Bronx Museum titled “Elegies.” “At the time, I was tired of my usual process of collaging,” he begins to explain. “I wanted to get away from the boundaries of the canvas.” Upon securing a plexiglass surface to the wall, Otero paints onto it with oil, as if he were making a figurative canvas. He starts with one image. Days or even weeks later, he paints another, related image on top and does this again and again, over time, accumulating overlapping layers of paint. Eventually, he takes the plexiglass down and scrapes the paint off completely; the “skin” that comes free is collaged with others (and sometimes with scraps of earlier discarded canvases) and then painted on some more. These draped compositions signal a ceding of control (it’s impossible to know what one will look like at the end) and introduce a dynamic physical presence in whatever space they are shown.

Yet, as the opening date for “Milagros” approached in April 2019, Otero sensed that something was missing. “I am intuitive and impulsive, which I used to find frustrating,” he tells me, but paying heed to the nagging questions that arise in your internal monologue does produce answers later on, if you are willing to wait. The artist had always collected small, sentimental objects and trinkets; he decided to add some of these tokens (droplets from chandeliers, bits of crocheted lace) to the negative spaces within the oil skins, their quiet placement barely perceptible at first, like a carefully planted clue. That urge to excavate a certain nostalgia—on our call we speak of Puerto Rico, the dining room table in his grandmother’s house, the smell of the ocean nearby—guides this latest show, in preparation for which Otero has been looking back at his figurative paintings from over a decade ago. “I’ve been feeling the need to go home for some time,” he says, after a long pause, and he wondered if there was a way to revisit the past while transporting it to the present. In his new works, these scenes and their literal furniture—bathtubs, couches, beds, drawers—begin to reappear in snapshots that are referential yet ambiguous, each a solitary journey in and out of space and time.

The way Otero marries some of the most canonical references of modern art history with the private markings of his own memory also traverses a contested terrain. These murky intersections—historical record versus subjectivity, abstraction versus figuration—are often upheld as unique, autonomous realms. But Otero insists that for him, art history is already extremely personal. The artists whose careers and lives he grew up studying comprise formative parts of his identity, and the dialogue that comes alive in his work refutes the assumption that broad strokes need overpower details. His skins and scraps manifest through a cycle of doing and undoing, a process akin to how our minds work. Information is continuously obscured and revealed, in the same way memory—the most unreliable of narrators—is constantly reconfiguring itself. Now, on the precipice of a new paradigm for how art will be experienced, how will Otero translate this distinct dimensionality to the infinite flatness of the screen?

in your life?

in your life?