“La Cucaracha,” South African photographer Pieter Hugo’s latest series, takes its name from the folk song we all know. For non-Spanish speakers who may only recognize the tune’s upbeat-tempo, its first verse roughly translates to, “The cockroach, the cockroach, / Can’t walk anymore / Because it doesn’t have, / Because it’s missing / Two little back legs.” The tune was popularized during the Mexican Revolution and its original meaning is not entirely clear. But it’s an image that sticks with you, a helpless, much despised creature, stumbling forwards and stumbling some more.

For the series, Hugo travelled throughout Mexico, from Tijuana to villages in southern Oaxaca, creating the images over a period of two years. Many of those documented are living on peripherals of society and—like the song from which the series derives its name—the photographs hold sadness and humor and levity, all in the same breath.

The work goes beyond simply rendering those on the margins with the dignity they warrant, or even deifying them, though it certainly enters that territory on a few occasions (in one image, an Oaxacan man poses in the hot sun with a crown of thorns; there’s no need for subtlety in Hugo’s oeuvre.) The images are a true world-making endeavor, casting subjects in fully-fleshed spheres awash with pathos, kindness, and the relativistic absurdity of everyday life.

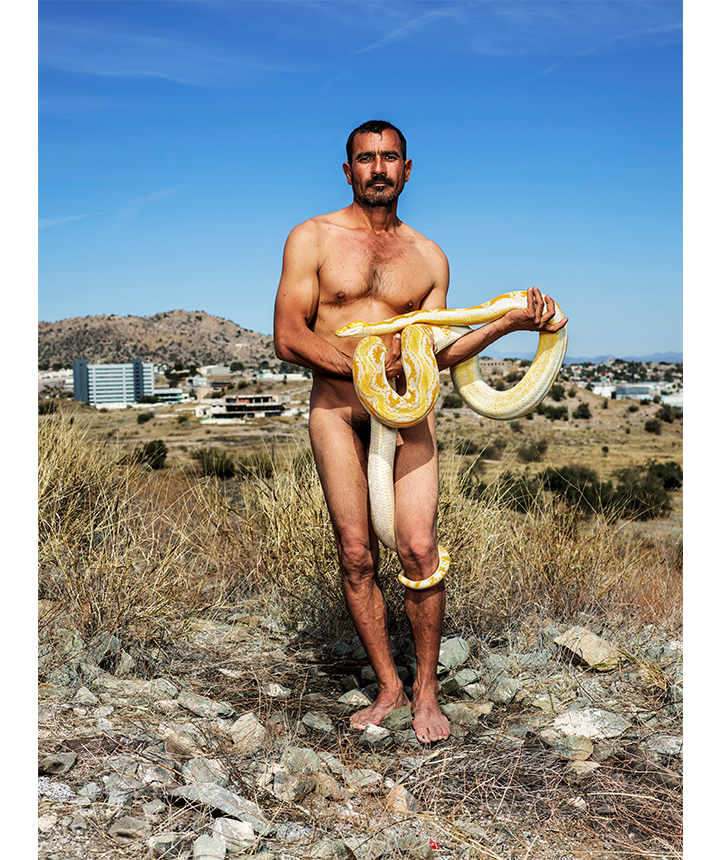

In The wedding gift, Juchitán de Zaragoza (2018), a bride sits in her wedding dress, holding a massive iguana whose tail extends to the dirt beneath the odd pair. In another image (The snake Charmer, [2019]) a nude man stands on the side of a dirt road, a long yellow snake wrapping around him and obstructing his genitals. With the figure’s awkward, contrapposto stance and slyly averted nudity, an allusion to Botticelli’s Birth of Venus is inevitable.

In Spoliation of evidence, Hermosillo (2019) a body is burning in a field, a ghastly site for Westerners raised in societies where death and birth happen outside of the home. We forget that, for much of the world, especially in communities where large extended families are the norm, these things happen in the home. In these communities, death is not viewed as a cosmic accident. This image is harked back to in another—the brilliantly titled, Burning bush, Oaxaca de Juárez, (2018), wherein we see a tall, desert cactus, engulfed in dramatic flame.

“La Cucaracha” may serve here as a nod to the possibility that life and death can exist in the same moment, one journey leading to another and the liminal space we stumble through, graceless or otherwise. La cucaracha, la cucaracha, can’t walk anymore.

in your life?

in your life?