When I arrive at 56 Henry to meet the painter and critic Walter Robinson for our tour of Condo, I’m 10 minutes late. He’s already had a popsicle with Ellie Rines, who runs 56 Henry, and Terese Reyes, whose Detroit-based Reyes Finn gallery is showing new works by Nick Doyle at 56 Henry for this summer’s iteration of the itinerant gallery exchange program. I met Walter in 2014, but my first memory of a conversation with him was a year later at a book signing for his exhibition catalogue Paintings and Other Indulgencesat Max Fish. I asked him to sign my book and as he was doing so, he said something about how I shouldn’t bother writing about art and instead I should go into financial management. Mostly I was flattered that he even knew I had ever written anything and I obviously didn’t take his advice. I hadn’t seen Walter in a few months when I asked him to walk around with me and share his thoughts on Condo. I was a little nervous when he started off along East Broadway saying, “I used to care about other people’s art, but now I don’t.” Nonetheless, he was gracious enough to share some thoughts. Follow along for the highlights of our LES Condo tour.

Nick Doyle at Reyes Finn hosted by 56 Henry

Cultured: So, what do you think of these?

Robinson: They make me think about this new Hal Foster book, Bad New Days. One of the things he thinks is happening is that artists are leaving the realm of the textual and going out into the world. It’s part of the new realism. Art can’t be about art anymore, it has to be about things in the world, the paintings as turning into actual things. The impulse to make the painting—

Cultured: Is becoming the actual thing. It’s like the materialization of the art object.

Robinson: The re-materialization. But they’re also very neat and very skilled.

Cultured: It’s all denim?

Reyes: It’s all wood and denim.

Robinson: It’s good that it’s not canvas, it fits my idea better. I’m seeing a kind of blue jean here. Did you drive a Ford? I used to have a Ford. Those are Marlboro Lights, right?

Reyes:Yeah.

Robinson:This guy and I have the same subjects. I’ve made a still life of cigarette packs, and I drive a Ford. We’re on the same team.

David Alekhuogie at Commonwealth and Council hosted by Baby Company

Robinson: Who is this?

Kibum Kim: This is David Alekhuogie, he’s one of the newer additions to the program. He grew up in Los Angeles, but studied in Chicago and at New Haven, but is now back in LA. He studied photography and is very invested in the objecthood of the photo image, so he experiments with the printing process, the materials and often makes his own frames. The images that are incorporated into this work come from his Pull Upseries that began a couple of years ago, when he was reading a lot of news stories about local ordinances being passed outlawing sagging pants.

Robinson: So these are saggy pants artworks? Awesome. Can’t go wrong. And these are photographs?

Kim: Yes. These are printed on canvas and then sewn together. He’s thinking about coded regulation of black men’s bodies and made these close-up photographs that are inspired by landscape photography and color field paintings—they’re kind of abstract to camouflage what they’re about. These triple bands of color lend themselves to flag-like constructions. For this body of work, he’s thinking about the flag as the conceptual basis of the pieces and thinking about flags as banners that represent certain kinds of communities and nation states, but these are all composed of disenfranchised bodies.

Robinson: You think they’re disenfranchised?

Kim: Yeah, well a lot of young black men in urban areas are not fully embraced and represented.

Cultured: Why do you question if they’re disenfranchised?

Robinson: Because it’s so much a language now. Is someone like Tupac Shakur disenfranchised? There’s this whole look, I don’t know what to call it—I’m an old white man—but it seems to have its cultural currency and it seems very powerful.

Kim: But that’s exactly it.

Cultured: It’s a form of cultural capital that is being exploited.

Robinson: Who’s trying to outlaw them?

Kim: Different municipalities, a lot of Southern towns.

Robinson: Some of these of are powerful, aggressive, even frightening. They’re macho. Is that in the works?

Kim: All of these images he took himself, but there are two works where he took an existing image—these two are of Tupac, who helped popularize the style and brought it to the mainstream. Tupac is a real hero to David and to a lot of young black men and what David talks about is how he had that kind of gangster rap swagger, but he also had very personal songs, and it’s his vulnerability that he was willing to share that really made him such a hero to urban black men.

Robinson: Is the wood used as a frame?

Kim: He’s thinking about how the body is the landscape, and these urban scenes as landscape. David was super invested in hip hop, and that’s the sensibility he brings to his work. A lot of his thinking behind his art practice deals with respectability. And as you said, now the sagging pants and hip hop rules all of the charts, but it took a long time for it to be recognized. David’s father immigrated from Nigeria and his mother is multi-generation African-American and he grew up in a household that was like, don’t dress like that. You should be respectable.

Cultured: I feel like you’re resistant to this work.

Robinson: If it didn’t make me want to resist it, then there wouldn’t be much to say about it. When I go see Joan Mitchell, I don’t resist those big colors on canvases, there’s nothing to resist there.

Kim: That’s exactly the point, this whole notion and idea of respectability. A lot of it is about bringing like hip hop sensibility and these kinds of styles—

Robinson: Into the fine art conversation, that makes it respectable.

Kim: No, I think he’s questioning it wholesale, whether this whole respectability is something we should care about in the first place.

Robinson: So you call it hip hop, this imagery and material.

Kim: Well, that is a big philosophy that informs his practice, because even though he takes his own photo images, he thinks about making work in a hip hop mindset which is a lot about sampling. He treats his studio as a place to look at things and he constructs these tableaux.

Robinson: I think they’re really good.

Group show at Bureau, hosting Standard (Oslo)

Robinson: What do you think these are? Money, purses, skulls, hourglasses, cars, spiders. What are those—like bad things you can put in a picture to make it seem bad? I would do lettuce, tomatoes, green peas.

Cultured: Pajamas.

Robinson: Pajamas, tennis balls.

Cultured: Hamburgers, French fries.

Robinson: These are Erica Baum, they’re old, from 1998, so what does that mean?

Rachelle Dang (friend and artist encountered in the gallery): I have some inside knowledge. They’re photographs from the Frick Library and it’s how they organize subject matter in paintings.

Cultured: Is that a secret?

Dang: No.

Robinson: I’m surprised they don’t have a press release for the show that explains everything.

Cultured: How are you supposed to know what it is unless someone tells you?

Dang: It’s a mystery, it’s like a strange poetic history.

Robinson: It’s just so bohemian. Try to be positive, not always about the bad things. I like this because this is painted [looking at Mikael Lo Presti]. See this here, and that there? Is that an accident, or is it really meant to be in this shape? I think it’s meant to be in the shape of a flying bird.

Dang: Yes, I think so.

Robinson: It’s like the spirit is escaping.

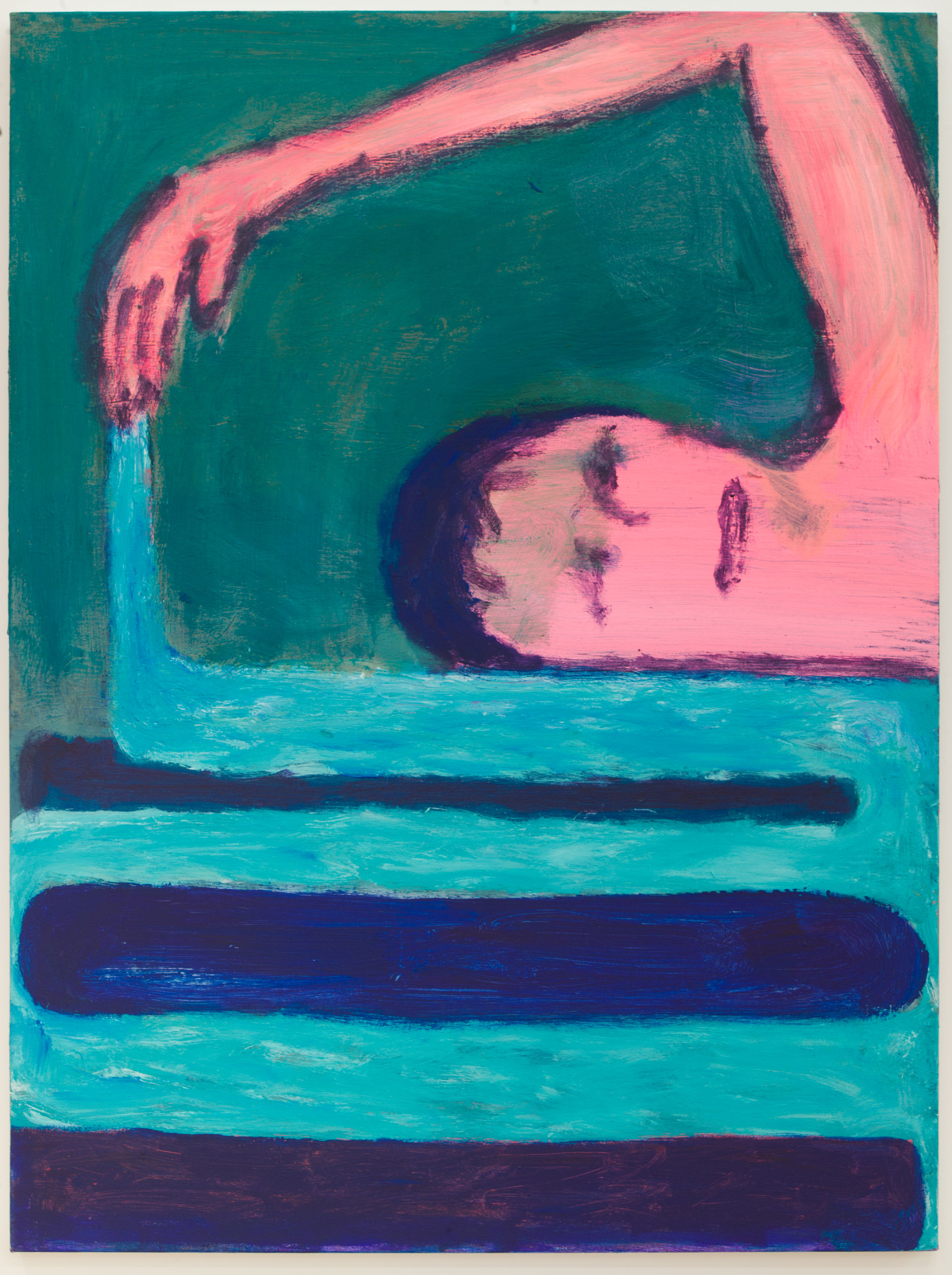

Katherine Bradford, Vaginal Davis and Jeffry Mitchell at Adamas and Ollman, hosted by JTT

Robinson: This ceramic—

Andrea Lounibos: It’s by Jeffry Mitchell.

Cultured: What do you think of these sculptures?

Robinson: I don’t see them as particularly gendered one way or the other.

Lounibos: They’re kind of coded and hidden, because Jeffry grew up very Catholic. So it’s hidden in a way with lots of little holes and playful things like flowers and animals to cover up and code the sexual innuendo.

Cultured: Do you think this might be a penis shape?

Robinson: No, I think that’s a bee’s nest.

Cultured: Oh, that’s a bee’s nest.

Robinson:It’s full of stinging bees, it’s a female form full of pain.

Cultured: I don’t see that. Oh, it’s a honeycomb. They’re going to get the honey, I see.

Lounibos: The glazes are kind of semen-esque. Jeffry studied porcelain and ceramics in Japan and China. He’ll be included in a show at the V&A in London early next year.

Cultured: I love the elephants.

Lounibos: Aren’t they lovely?

Cultured: Yeah, they are.

Standing on Rivington Street, at the intersection with Freeman’s Alley we take a minute to process.

Cultured: Did you have any thoughts on those Jeffry Walker and Vaginal Davis works at Adams and Ollman?

Robinson: We really should’ve looked at Vaginal Davis works closer. Identity is so much a part of art these days. In the old days, you didn’t care about the artist’s biography, but now it’s a kind of secret ingredient. So Vaginal’s story affects how you look at the pictures and how you think about it.

Cultured: Even as a painter it affects how you look at the work?

Robinson: It has to. Identity is such a part of everything, like with David Alekhuogie’s work at Company, the pitch was about how he was interested in hip hop. It forms the aesthetic, the identity of the artist obviously informs the aesthetic.

Cultured: What about the porcelains?

Robinson: To me what’s interesting about them is that it’s a less familiar material, but that aesthetic is really well established. Instead of using trash like Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt who since the 70s has been making these amazing rococo constructions out of glitter and cellophane. that have a very gay aesthetic, this guy Mitchell is going more with the fine craft route. They’re finely crafted pieces, but since they’re little teddy bears, they have this infantilism. They’re beautifully done, very charming. It’s almost like a children’s book illustration—a beehive swarming with bees, but in in this case they are bee-sized bears. How about that? Anything goes. It’s a sensibility thing. But can we measure things in terms of how avant-garde they are? I think the show at Commonwealth and Council was more avant-garde. I was talking with Chris Dorland recently about the idea of work being badass or not. Did we see anything that was badass? The list of subjects—axes, skulls, skeletons?

Cultured: That’s esoteric, maybe it’s badass, but you would need a lot of prior knowledge to do anything with it. Otherwise, it’s just words.

Robinson: Is the porcelain with the little bears esoteric?

Cultured: No, but it has layers. Someone could look at it and be like, oh that’s so cute and then think a little more and maybe see more there. You get out of it what you bring to it.

Robinson: Absolutely. I like following auction prices because that’s a scale you can measure things on, this picture is worth $50M so it’s obviously better than the one that’s worth $25M. If you think about badass as an aesthetic measure it can be a way of measuring avant-gardism.

Cultured: I’m not sure anything that we’ve seen today is badass.

Robinson: I think the Alekhuogie works have to qualify as, doesn’t they?

Cultured: Maybe I need to understand more what you mean by badass.

Robinson: It has to be obvious, like you know what badass is.

Cultured: But everyone has a different idea of that.

Robinson: Not of badass. No. Everybody knows what that is. It’s a little bit frightening, it’s tough, it’s mean, it’s brave, it’s challenging, it’s rule-breaking. Everybody knows what badass is. Even if it is packaged and administered by avant-garde.

in your life?

in your life?