It’s a misty June day when I find myself farther out on the N train than I’ve ever been before. I’m going to visit the painter Arcmanoro Niles and assume I’m heading to a former warehouse or factory, but instead find myself on a picturesque block of townhouses with residents who seem to have been there for decades. Niles has lived and worked on the top floor of one such house for five years, since his days as a student at the New York Academy of Art—not a school one often hears in the downtown circles in which the young Washington D.C.-born painter is carving a name for himself. Since graduating in 2015, Niles has had two solo shows at Rachel Uffner Gallery, the most recent of which earned him a nod from Roberta Smith. His work is now included in “Punch,” curated by Nina Chanel-Abney and opening today at Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles outpost, following its celebrated New York run last fall.

Niles greets me, dressed in what seems to be an all-black uniform of sorts, accented with a wide-brimmed black wool hat, chunky silver jewelry and boots. We ascend the three flights to the studio, on the other side of which is his living space. I begin asking him about the possible tension between the classical training he received as a painter and the contemporary context in which he is working, but my questions quickly feel irrelevant. Whatever paradox I thought existed simply doesn’t enter into Niles’s thinking about his work or about painting in general. So we go back to the beginning.

It seems clear—though the artist denies it—that he displayed serious talent as a child. He attended an art high school, where he made Rothko-inspired abstractions up until his senior year. “My painting teacher showed me a movie about Caravaggio and I fell in love with him,” he recalls of the Italian Baroque artist who continues to be first and foremost in his mind. “The way he took these biblical stories and made them about his life in Rome—I wanted to do the same thing,” he says. “I would pose my friends like Caravaggio paintings and I started putting myself in Caravaggio paintings.” After learning about the Italian master, Niles immediately started taking figurative drawing classes at the Washington Studio School, paying for the courses by working at Ben & Jerry’s and then continuing his studies at Montgomery Community College before moving on to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and eventually to the New York Academy of Art.

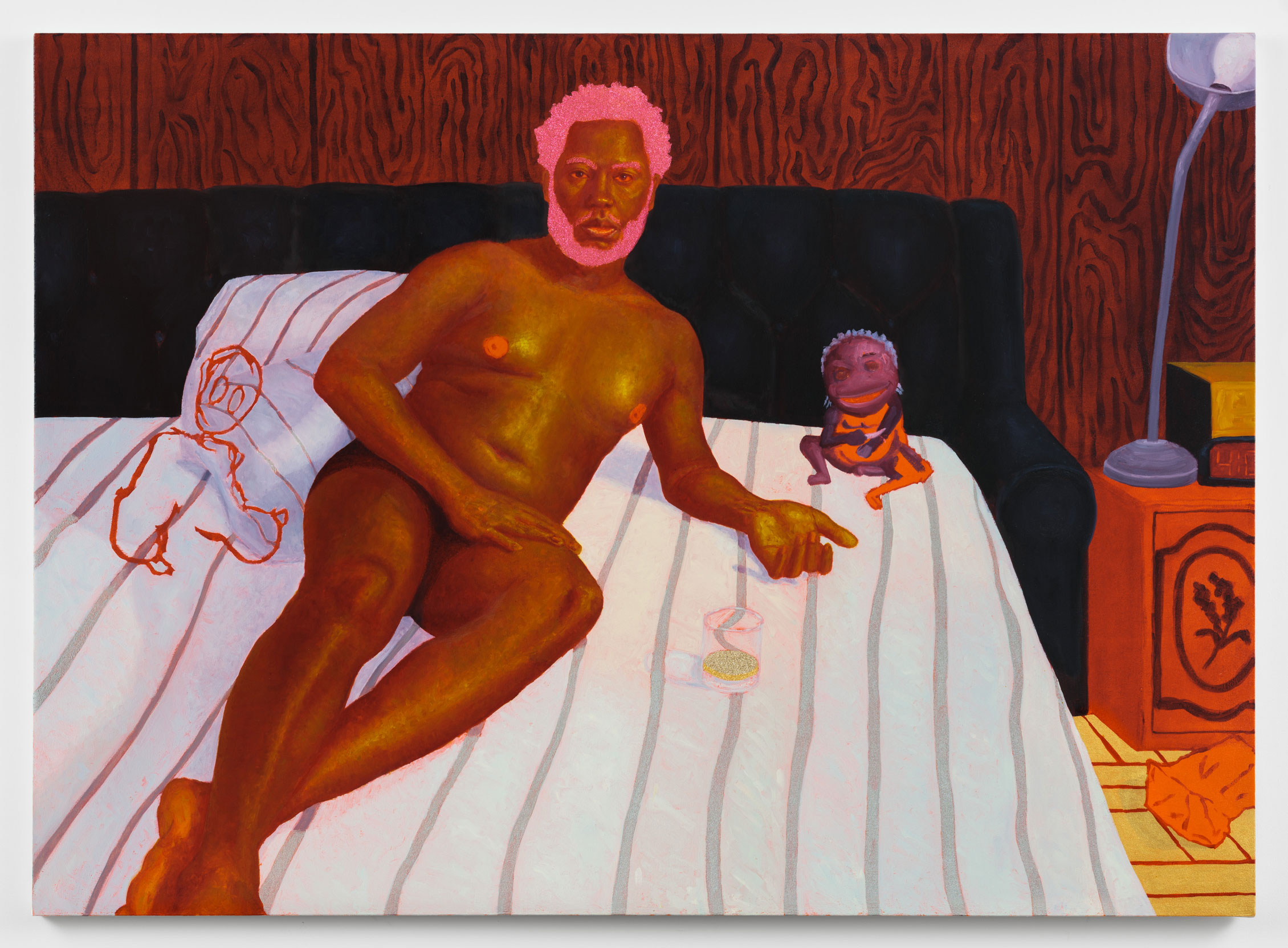

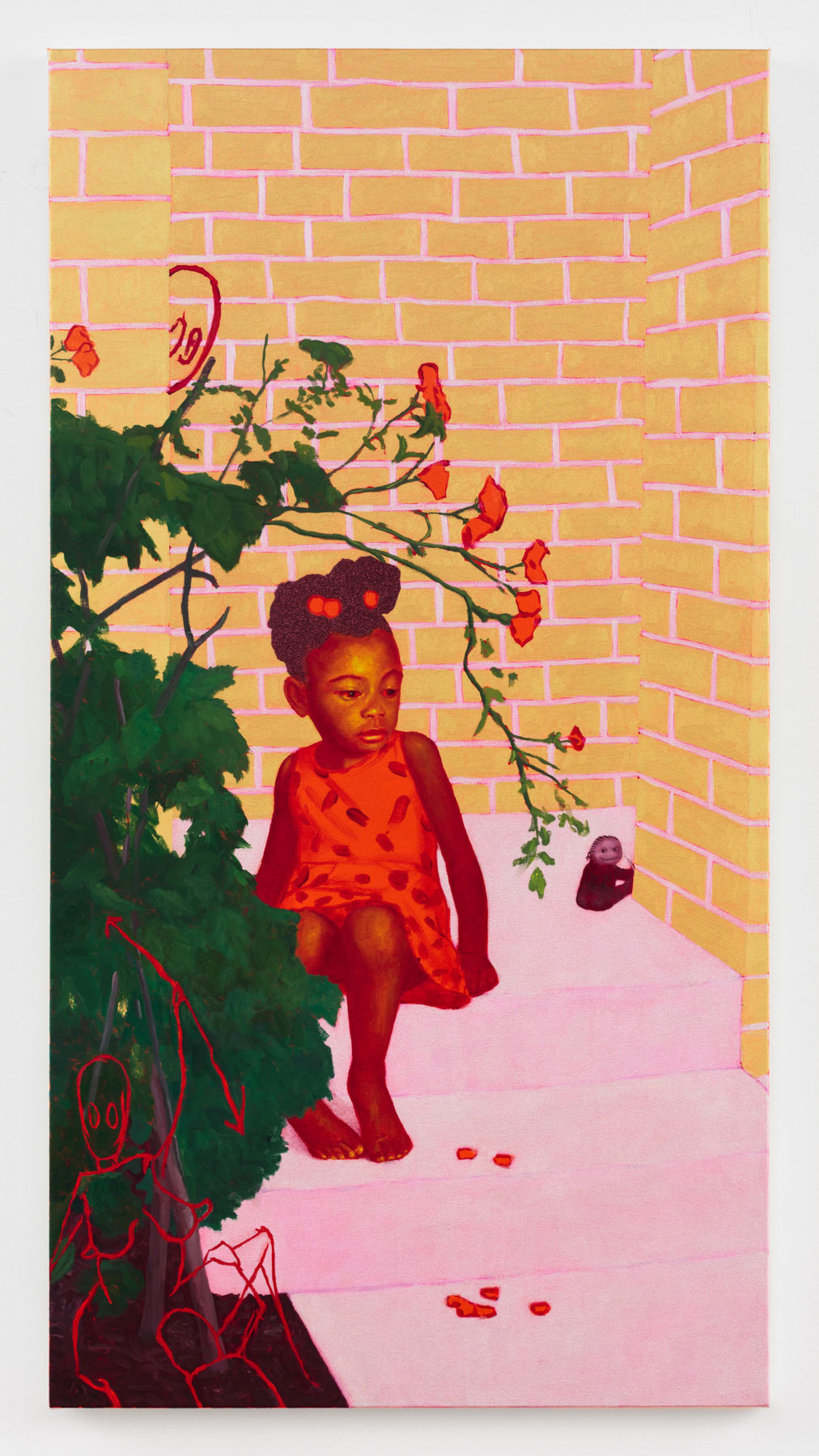

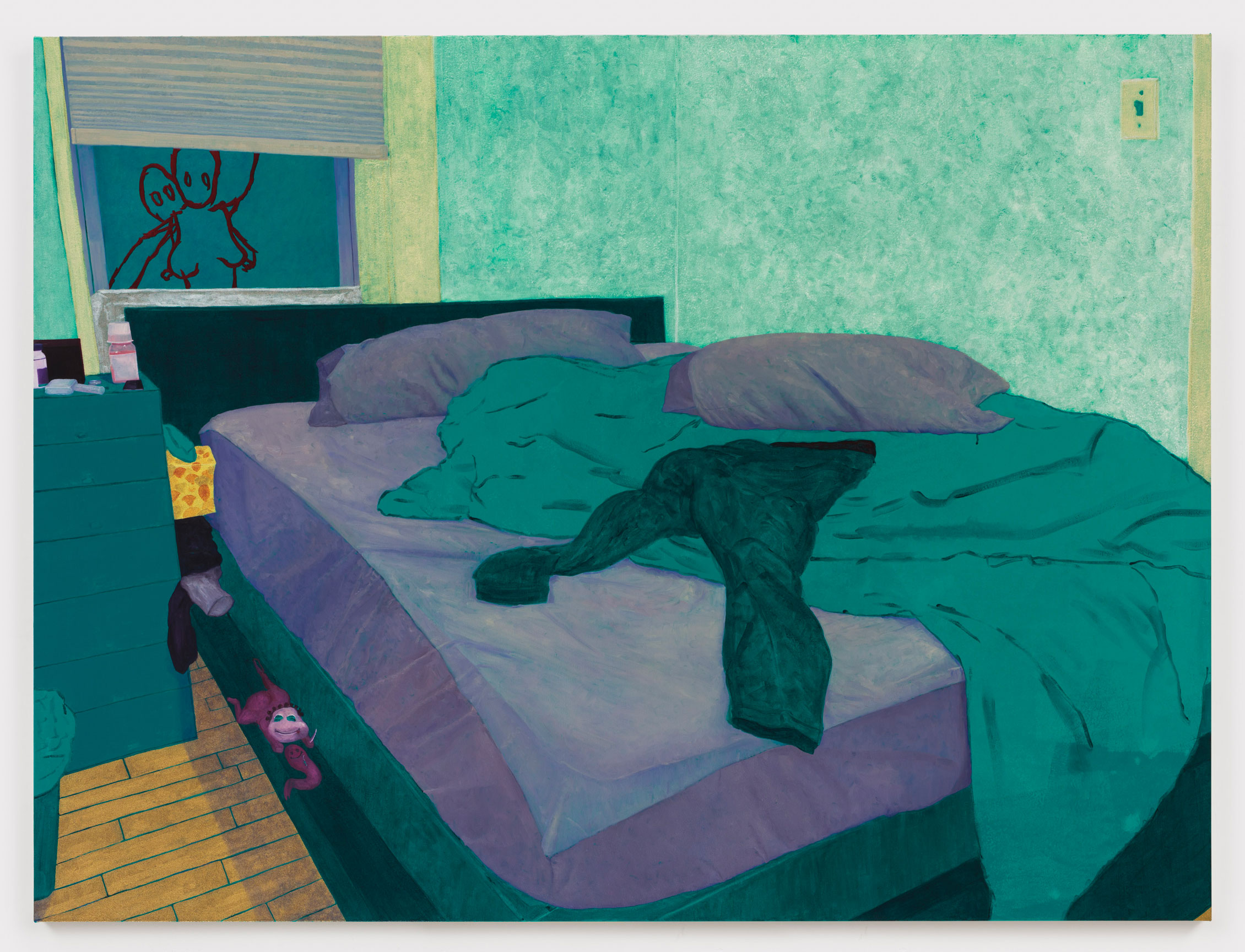

The works in the studio on the day I visit are a mélange of portraits: some of people, some of places, some of moments. They’re not representational per sé—fictional cartoon-like characters derived from Egyptian fertility sculptures have a role in several of the works—but there is a mastery in the depiction of the figures that is rare in contemporary painting. Two self-portraits of Niles as a child are tender and perhaps a little nostalgic, but more so they reveal someone looking at and into themselves, trying, honestly, to parse it all out. “I think a lot about Caravaggio’s painting, The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew. There’s this guy in the middle towards the bottom who is getting stabbed and Caravaggio painted himself in the background running away,” Niles explains.

But for whatever tumult Caravaggio’s life entailed, his biggest mark on history was his development of chiaroscuro—a means of creating narrative drama with exaggerated light and shadow, a device Niles plays with often. “I always think about what’s going to be the brightest or what’s going to reflect the most in a painting, and how that is going to make a viewer move around,” he explains. “I’m most interested in how to organize the light in a work. People say Delacroix was a colorist and Caravaggio’s work was more tonal, but I don’t want to compromise either of those in my work.”

Naturally intertwined with these Renaissance approaches are Niles’s personal experiences. The artist draws from his childhood memories, the people in his life (his mother is a favorite subject) and the places he frequents, working with a saturated palette of oranges, blues and purples and often framing faces in halos of glitter. Niles mentions an influential studio visit with Eric Fischl from his time at the New York Academy of Art, how something about their conversation about figuration freed him up a little and let him step back from strict narratives. As a representative painter whose work offers a cultural critique, Fischl is an understandable reference point for Niles. But where Fischl seems resigned to cynicism, Niles allows for a vulnerability. The resulting fissure creates a light that offers a space for contemplation both personal and pictorial.

in your life?

in your life?