Kohshin Finley’s large-scale realist portraits tell stories—just not his. “As a painter and storyteller, you realize sometimes the story you gotta tell isn’t your own. You sometimes have to make the podium your friends can stand on,” explains Finley, sitting in his Hollywood studio on an atypically rainy LA morning. I listen to him describe his practice while glancing back and forth at the results: the striking black and white portraits stacked against the walls, part of a larger series that will debut in a not-yet-announced solo show this fall.

The captivating 3×4-foot portraits are set against subtle grayscale backgrounds, and the faces—namely the eyes—stand out, hinting at something deeper, a narrative Finley takes very seriously. “I have my friends come in, and we catch up,” he says. “From there we start talking about things they’ve gone through, and that becomes the heart of the painting, the white marks.” The paintings—portraits of friends and family—evoke an intimacy and familiarity. “Making a safe space in my studio is most important,” says Finley. “The actual painting itself is only 30 to 40 percent of the process. A lot of the pre-work is talking to my friends and doing right by them, making sure I am showing them how they want to be seen.”

Finley’s subjects are mostly black and brown people, a reflection of his own heritage and community. While he stands among a growing number of young African American, Latinx and other artists of color, Finley would rather avoid categorical labels in lieu of the narratives and nuances within all multi-cultural communities. “So many things within that spectrum can’t be so simply labeled,” he says. This view informs Finley’s approach to his paintings. “In order for the paintings to be read in the way I want them to be, I had to remove color from the practice. Color is another lens for people to have to analyze and get through,” he says. “Removing color was my way of operating like black and white photography; you get to see the image and connect with the work more directly.”

Finley’s technique successfully translates into strong connections with viewers. One of the pieces I notice in the studio, Get Used To The Hoodie (2018), depicts a defiant Jesse Williams, the actor and Finley’s friend, who represents a voice of resistance and activism. Williams’ face and neck are brushed with loose white strokes, symbols of deeper and more personal insights into the identity and racial politics of black men in America—one of the many cultural narratives within Finley’s paintings.

Finley’s primary goal for his current series, he says, “is to make sure we have prominent space within the four corners of an artwork,” a commentary on the history of figurative portraiture and the limited representation of minority artists painting minority subjects within the canon of arts education and institutions. “I want to show the possibilities,” Finley continues. “That’s very special that I’m adding to legacy, to history. It’s at the core of my practice.”

Born to an African American father and Mexican mother, Finley grew up in South Central surrounded by creatives. His parents worked in fashion, operating businesses out of their home where Finley says he “literally grew up on the cutting table” and witnessed his parents “drawing, designing and making the clothes.” He adds, “As I grow older, I continuously realize how rare it was they never told me to stop drawing. They never wanted me to be a doctor or a lawyer.” Finley’s parents planted the seeds of creative enterprise, encouraging their children to pursue happiness over more secure financial endeavors, a rare sentiment among working class minorities and one that has ultimately served as a guiding principle in Finley’s journey as an artist.

Growing up, Finley always stood out as the “art kid.” He was one of only a few students in his high school graduating class to go to art school, enrolling in Otis College of Art and Design, where he began as an illustrator, primarily operating in pen and ink. Finley started to chart his own path by exploring other artistic practices such as writing. “I dabbled in a lot of other stuff and visual styles trying to figure out my own style,” he says.

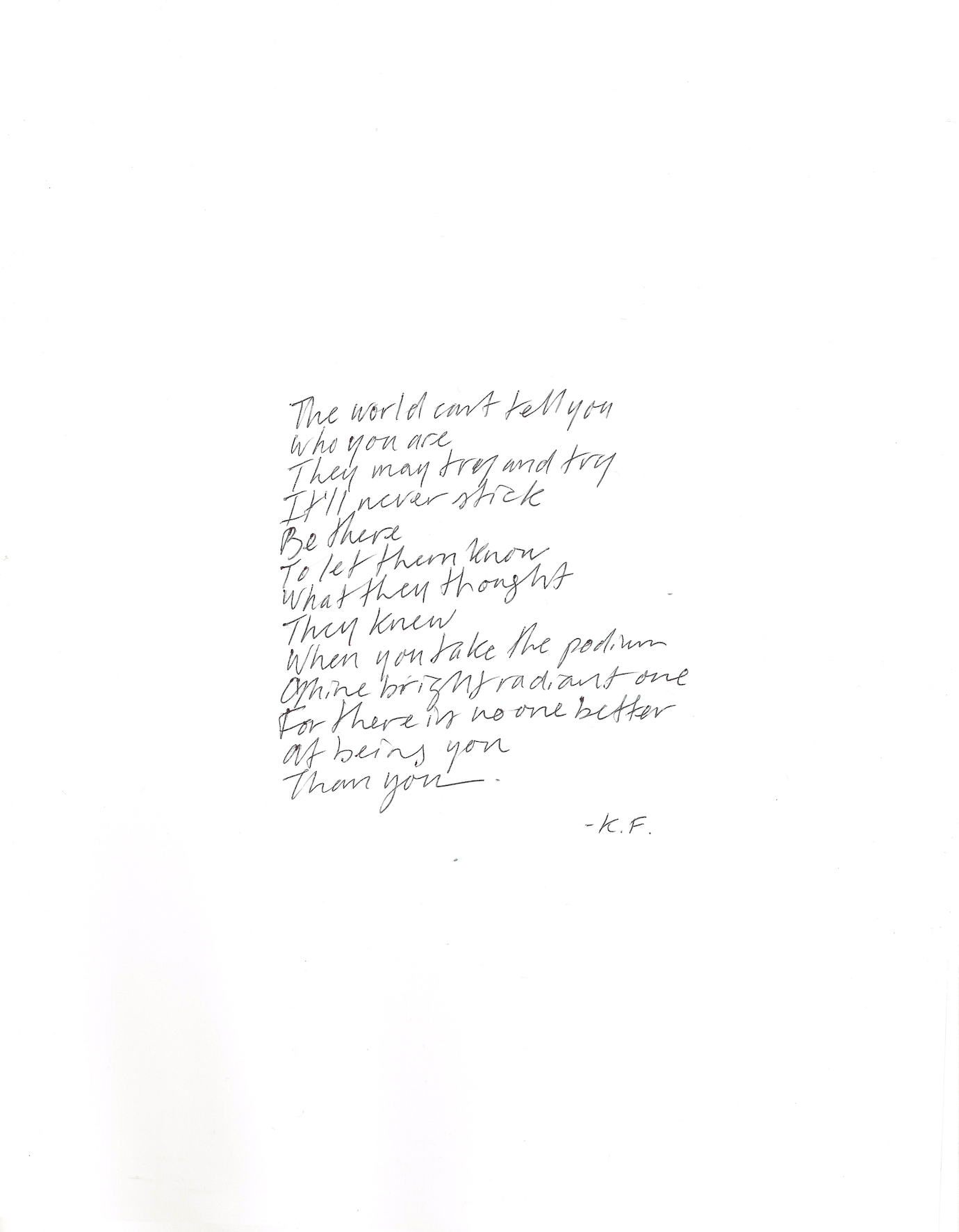

Finley credits his friend Augustine Kofie as a pivotal influence. “He told me, ‘All you can do is just keep making. The style and everything else [will come] naturally.’” That advice led Finley to include text and poetry in his work. He says, “You keep making stuff, and you realize this thing keeps appearing in my paintings.” The incorporation of poetry and text—usually only partially legible, if at all legible, under the layers of gray paint— according to Finley, “is something organic that just made sense.” He explains, “Once I dedicated myself to creating certain things with narrative, everything else sort of clicked.”

His friendship with Kofie was one of several associations with artists who were older and more well-known that proved formative for Finley. “It gave me something to aim for,” he says. “I wasn’t aiming sideways at my contemporaries at school; I was aiming for the guys that were outside of it.” His one-on-one research in the field with artists such as Kofie, El Mac and Christian Clayton served as unofficial internships from which Finley gathered critiques and advice. “I always looked up to them,” he says. “They were the ones that were doing what I wanted to do.”

Finley now pursues exactly what he wants to do. As his practice and collector base expand, so do new exhibition opportunities. He is currently part of the group exhibition “Plumb Line: Charles White and the Contemporary” at the California African American Museum (on view through August 25), his first museum show in LA. Finley also does commissions, increasingly frequent work he welcomes. “When someone wants to celebrate a certain thing about their journey, I help them highlight it,” he says. “It’s not just a painting at that point; it’s an artifact of history. That bond you create with your sitter is forever.”

This recent success hasn’t stopped Finley from remembering what he’s learned in the past: “You have to be confident in your own practice and know that the work always comes first.” When it comes to his future as an artist, it turns out Finley is boldly writing his own story.

This story was originally published in LALA Magazine.

in your life?

in your life?