In a time of global crisis, contemporary art may seem frivolous. But I believe art is still a viable path to salvation. Historically, art was part of the disciplines of magic, science and religion, and this may still be true in Venice.

The reality of climate change—rising tides, increased storms and the disappearance of a million species along with countless natural habitats—is the most urgent threat facing us all, and the impetus for many artworks and exhibitions here this year. Some works offer scientific teaching moments via adjoining texts and videos, and today’s precariousness is also emotionally and viscerally experienced with meditative art, to greater effect.

Inside the Giardini of the Biennale, the Nordic Pavilion is beautiful and firmly rooted in science. Ane Graff’s work takes a relational approach to living bodies, presenting objects created with algae, bacteria and minerals inside anthropomorphic glass boxes. The work is unstable, constantly interacting with its environment, and refers to the extinction of “immune regulating intestinal microbes,” according to the exhibition text. Ingela Ihrman’s seaweed pieces grapple with algae, the liquid origins of life, and present it tangled up with plastic. It’s fresh to see artwork presenting our reliance on diverse, tiny, non-human life forms—invertebrates, microbes, insects—but it’s too didactic for my taste. The exhibition is called “Weather Report: Forecasting the Future.” I don’t believe this science-based prediction allows space for magic.

Nostalgia and longing for lost ground is characteristic of the Canadian Pavilion’s One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, by the artist collective Isuma. The One Day video installation is a dramatic reenactment of a 1961 visit by a government agent urging this nomadic tribe to move off their land onto a government settlement. Piugattuk resists and has no desire to leave his land so his children can join Canadian society, go to school and make money. Another component, Silakut Live from the Floe Edge, is a live-feed of Igloolik reactions to a contemporary mining company’s proposal to build a railroad across walrus breeding ground, which happens to be on Piugattuk’s former land. The third component, Isuma Online, is an archive of indigenous films and videos in 75 languages, which are also at risk of extinction as a result of capitalist expansion and environmental exploitation.

While Isuma presents reality, albeit with a historical reenactment, Larissa Sansour’s exhibition for the Danish Pavilion includes a science fiction film of a post-environmental disaster reality and a related installation, Monument for Lost Time. The film, In Vitro, is a poetic yet nightmarish dream, where time is suspended and home becomes a void. In Vitro evokes the reality of post-war refugees as well as those left homeless after the natural disasters that frequently occur now. Across from the screening room, Monument is a massive, droning, black hole, untouchable to the viewer yet threatening to consume us. It vibrates from its core as an abstract yet very real embodiment of the powerful Nothingness that awaits us all.

Outside of the Giardini and Arsenale, exhibitions engage decaying architecture and canals of Venice, highlighting the city’s and our own vulnerability as well the power of water to connect. Ocean Space currently occupies the still under restoration Church of San Lorenzo with marine-related works by Joan Jonas, as well as a powerful, cloistered sound field by Dark Morph that transports us to the bubbling, living interface between the sky and the ocean’s surface. Outside, the artist Melissa McGill has orchestrated Red Regatta, a water-based performance engaging the Venetian tradition of vela al terzo, an iconic part of Venetian life threatened with extinction by mass tourism. Together with 250 local partners, McGill has painted 52 sails in bold shades of red and will unleash these sailboats at once as an alarm call several times throughout the Biennale. In addition to the water-based performances, the boats will be parked in symbolic locations to raise awareness of authentic Venetian culture and traditions.

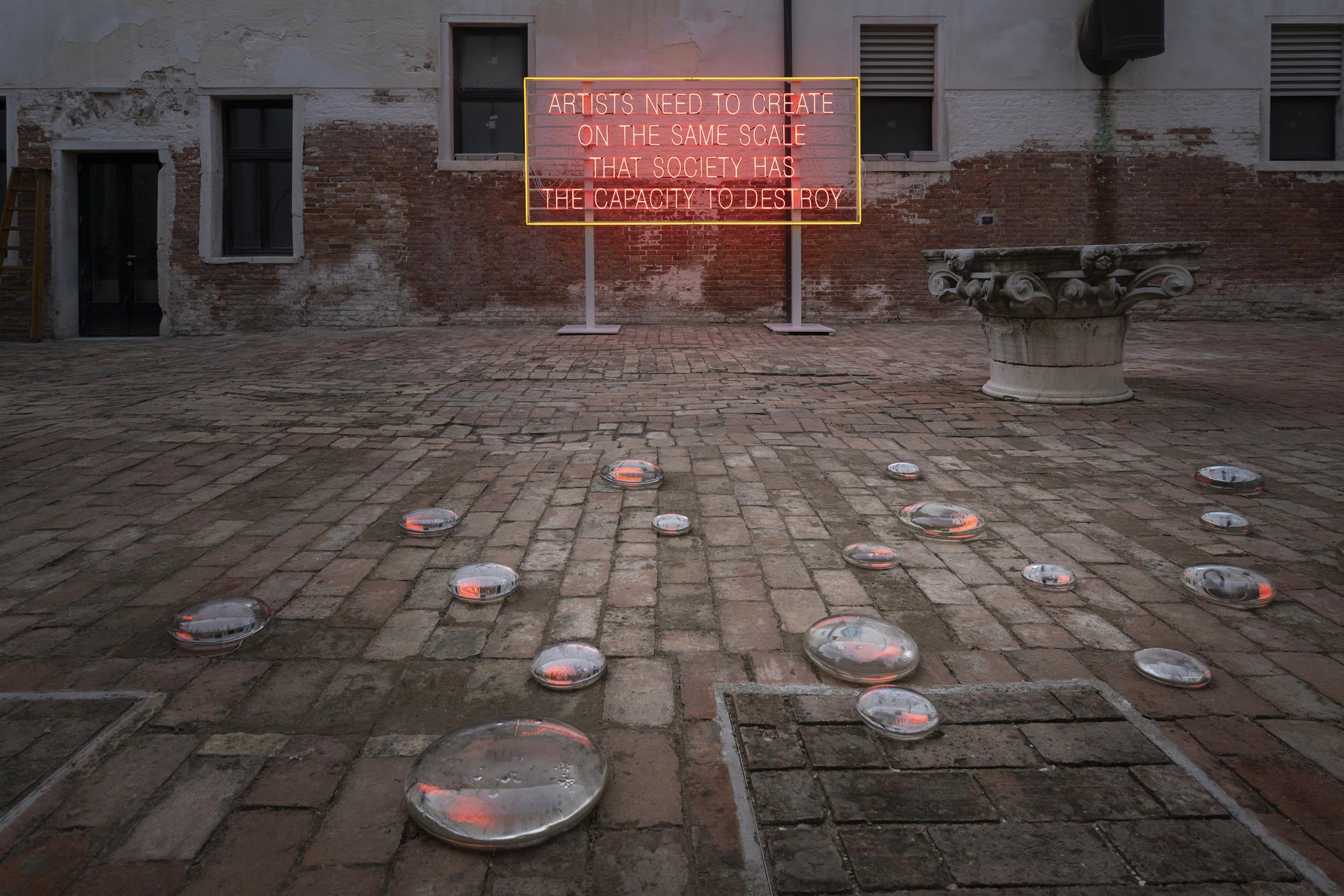

Towards the edge of the city, Brooklyn Rail Curatorial Projects presents “Artists Need to Create on the Same Scale that Society Has the Capacity to Destroy,” named after a neon work by Lauren Bon which is included in the exhibition. The venue, Chiesa degli Penitenti, is a now vacant and crumbling chapel once used by repenting prostitutes, which suits the theme of the show. Entering, we encounter a fallen skeleton-like tree, traversing a massive, existing hole in the floor in front of an altar piece. Both the tree and the items on the altar consist of burnt material Bon brought to Venice from California wildfires. Wolfgang Laib’s floor-level piece presents a series of gold-tone boats suspended in water-like piles of rice. Each grain of rice evokes a drop of water, necessary for movement, growth and exchange between things, yet momentarily frozen in time. In addition to setting up a satellite office here for the duration of the Biennale, the Brooklyn Rail will host full moon parties celebrating the power of the cosmos to support and sustain us, even in these precarious times.

in your life?

in your life?