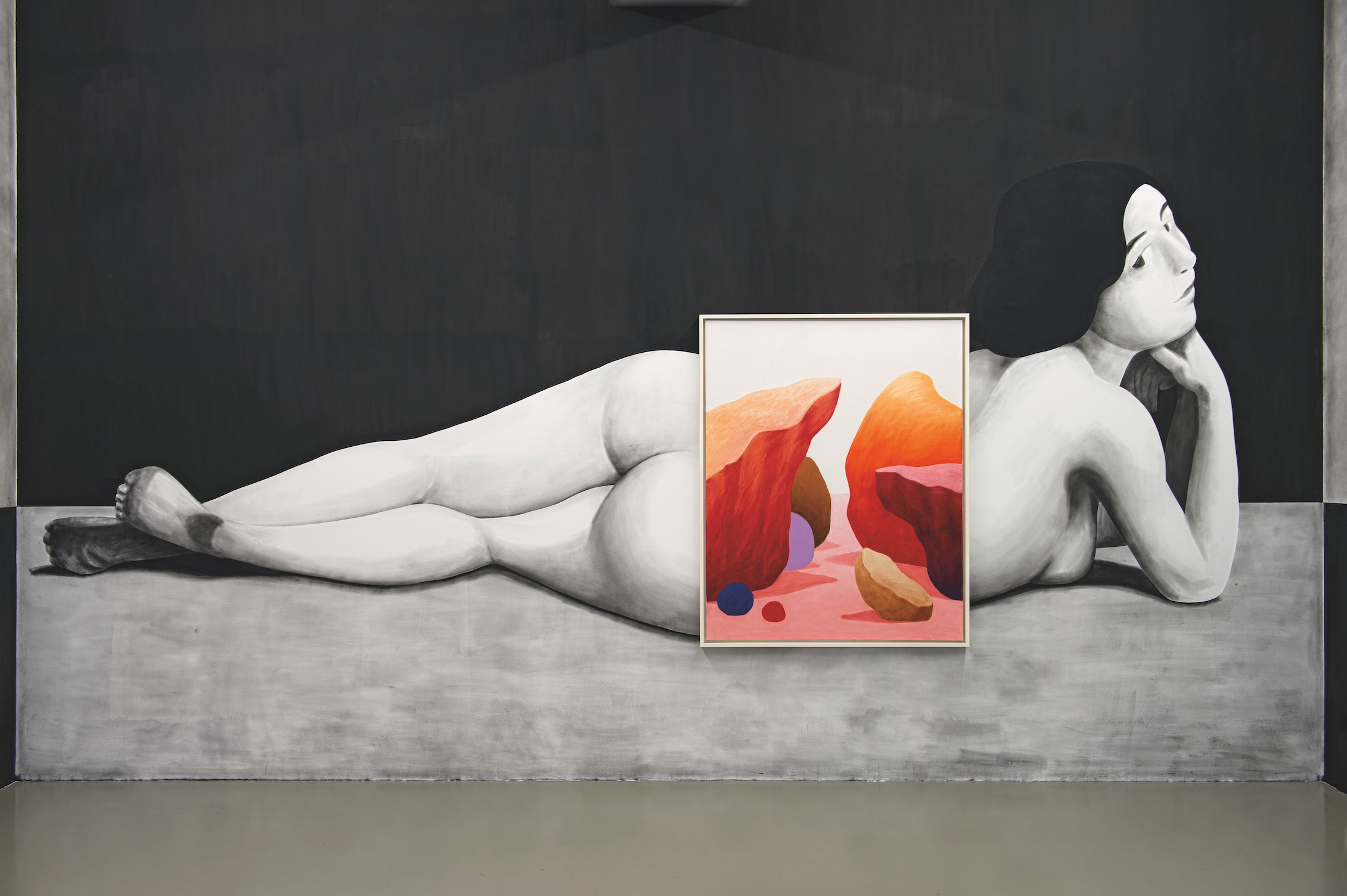

When the Magritte Museum in Brussels shipped some of its well- known René Magritte paintings to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art for an exhibition there, curators chose 38-year-old Swiss artist Nicolas Party to fill the void, literally. On the museum’s empty walls they hung Party’s mysterious, intensely saturated pastels. In spirit, they evoked something of the Surrealist master himself.

Party works in a figural vein, depicting mountain landscapes, a picture of an owl or a tree, a pair of stylized human faces. Even though you can read the shapes, each image always carries with it an uncanny strangeness. The forms are cleanly and sharply delineated, but the lack of smudges, drips or any messiness doesn’t make them any more fathomable.

The art world has taken note of Party’s talent, which refreshingly fits no known current trends. In 2017, he had a solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, and he is now represented by Xavier Hufkens Gallery in Brussels, the Modern Institute in Glasgow, Gregor Staiger in Zürich and Karma in New York.

Party’s art-historical reference points are not the usual ones you hear from contemporary makers: Ferdinand Hodler, the Swiss landscape painter; Giorgio Morandi, the ethereal still life artist; and Odilon Redon, the French symbolist who utterly mastered the pastel. “I’m the opposite of a lot of other artists,” says the affable Party, seated in his Bushwick studio and surrounded by his artworks. “I have very few references after the American revolution.” He doesn’t mean 1776, but the 1950s and the New York School’s shift to abstraction. “Weirdly enough, it’s why my subjects are important,” says Party. “They’re symbolic. A tree might seem one of the most banal things, but the meaning and the metaphor in a specific item—a face or a cat, or whatever it is—is very important for me.”

Party currently lives between Brussels and New York, but is shifting his life to the American side more and more. He was born in French-speaking Lausanne, Switzerland, and started drawing early. “Since as far as I remember, my family always told me, ‘You’re an artist,’” he recalls. “I was really having a lot of satisfaction with it at a young age. Still to this day, the moments that I feel the best are when I’m in my studio.” He sold paintings to his family, and even to his dentist, as a teenager.

For a time, he led also a double, mildly lawless life as a graffiti artist. He began locally. “My friend had a little moto, and I would be on the back and we would head off,” Party says. “I started slowly. I was doing the train tracks a lot and then in the streets, in the city of Lausanne a little bit.” But he then expanded to other countries. “That was obviously super fun because we would draw all day long with 10 other friends, taking the car at night. That’s the best thing ever, right? Because you get chased by the police. I got caught a few times.”

Party managed to transition into polite society, getting a BA from the Lausanne School of Art and an MFA from the Glasgow School of Art. Although he spent a decade or so working in the gig economy, he was always making his own art, tending toward two dimensions but also working in sculpture; to this day, he makes 3D-printed objects and paints them, too.

Finding one’s medium is one of those crucial life passages for an artist—with Party, you can almost hear the click of something falling into place. “I love pastels so much,” Party says. “I came to them because at one point I was doing oils, and my main problem was that I couldn’t stop editing the painting. Oils allow you to endlessly retouch.”

There’s a perfectionist streak in him, as there is in pretty much all artists. “With pastels it’s kind of the exact opposite,” he says. “You can layer and layer, but you can’t start over. The nature of the medium is much more direct. Nothing dries or is wet—it stays exactly how it is.” Party’s color sense is very distinct to say the least. “I’m always trying to get away from the high contrasts, but it just keeps going,” he says. Party uses a huge variety of tones, and there’s not a lot of repetition, except for an ultramarine blue that crops up in multiple pictures. He has some 2,300 different hues stacked up in boxes in his studio. “It’s more like house painting,” he says. “You have the options, and you choose this one.” As for the source of his palette, “You never know where your tastes are from,” he says. “But for 10 years I did a lot of spray paint. And basically you use super strong contrasts for a very obvious reason: It has to be very visible from far away.”

From Party’s own perspective, his current success and acclaim is as much a puzzlement as the scenes he depicts. It’s not that he’s disingenuous, it’s not that he’s not grateful; he’s just aware that luck is a factor. “Some great artists don’t sell, and some very bad artists sell a lot,” Party says. “Every artist that starts to sell a lot will have this strange relationship with that fact—but they’ll always take it.” He laughs, but something of the deadpan effect of his pictures comes through in his reaction, too. Acknowledging that life is a mystery somehow becomes him. “It doesn’t mean it’s good, it doesn’t mean it’s bad,” he adds. “It’s just what happened.”

in your life?

in your life?