This year marks the 25th anniversary of New York’s Armory Show, the anchor event of the city’s sprawling art deluge—often called Armory Week—that includes numerous satellite fairs, cultural programming, and public art openings. Founded in 1994, the show started with just five dealers displaying works in Gramercy Hotel rooms, then called The Gramercy International Art Fair. Prohibited from hanging art on the walls, exhibitors arrayed pieces across hotel beds instead. In fact, during the first show, Tracey Emin, known for her neon and provocatively personal sculpture, was indeed laying in one of the beds, under the covers.

A quarter century later, the Armory is an international fixture hosting 198 galleries from 33 countries, with booths and site-specific installations along Manhattan’s west side. Through Sunday, modern and contemporary art, alongside the fair’s signature large-scale, site-responses Platform projects, populate the architecture of Piers 90, 92 and 94. Fairgoers should not miss this year’s specially commissioned passageway, Star Ceiling by Leo Villareal, who executes custom computer codes to create mesmerizing light patterns. Presented with Pace Gallery—and already an Instagram ado—the 75-foot LED canopy re-invents a tented corridor between Pier 92 and 94. Villareal’s cosmic plafond is the largest digital artwork in the fair’s history.

There are ample standouts this week, but among the fair’s most remarkable single-artist presentations are socially and politically engaged artworks that reflect the tenor of omnipresent realities, from commentary on consumerism and pollution to gender representation and race. A gateway to the North American collector, the Armory show, like the World’s Fair in 1939—the departure for this year’s Platform section, Worlds of Tomorrow, curated by Sally Tallant, newly appointed executive director of the Queens Museum—offers hope and resilience in the face of geopolitical uncertainty, explains Armory director Nicole Berry. Here are Cultured’s 6 Armory selections highlighted for the 25th Armory.

Florine Démosthène at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery In a booth of an eye-popping green, Seattle-based Mariane Ibrahim Gallery (moving soon to Chicago) presents a solo exhibition of the Haitian-American artist, Florine Démosthène’s glitter, gold leaf and mylar collage portraiture. Using these unexpected materials, Démonsthène, a graduate of Parsons the New School for Design and Hunter College’s Master of Fine Arts, deconstructs the black female persona and commodification of the black body. Although, in the artist’s words, the work transcends a racial framework and is more globally invested in the internal battle of all human beings. “Certainly there is a part of my work that references race,” Démonsthène told Cultured. “But I think even more so this work is about gender.”

Pascale Marthine Tayou at Richard Taittinger Gallery Some installations at the Armory are destined for iconic status, and Pascale Marthine Tayou’s Plastic Bags, part of the Platform presentation, is one of them. Presented by New York’s Richard Taittinger Gallery, the Cameroon artist’s hulking cyclone, comprised of more than 25,000 multicolor disposable plastic bags, hangs from a 20-foot ceiling truss that dominates the center of Pier 94’s Town Square. During preview hours, fairgoers eagerly slid beneath to behold the sculpture’s hollow core.

Tayou, a participant in the Venice Biennale and Documenta 11, elevates a universal, castaway object, used by all social classes, to high art— challenging viewers to contemplate the scale of their waste and destructive footprint. In the vein of Paula Crown’s larger-than-life solo cup Jokester, this artwork is dramatic and playful yet carries a weighty undercurrent of Western excess.

Moffat Takadiwa at Nicodim Gallery Sculptor Moffat Takadiwa, who lives and works in Harare, Zimbabwe, describes the junkyard as his artistic muse. From afar, the artwork appears like textile, though it’s fashioned masterfully from plastic and metal. Weaving discarded computer keypads, spray bottles, toothbrushes, and a myriad of found objects, Takadiwa’s ritualistic and evocative tapestries recall the legendary El Anatsui’s liquor bottle cap wall assemblages.

Takadiwa transforms 21st-century refuse—sourced partly from ocean flotsam— into a shimmering, complex language, communicating concerns with consumerism, inequality, and the environment. One is hard pressed to stand before the majestic pieces, especially the mosaics of found computer keys, without contemplating the profound implications of planned obsolescence in modern life.

Peter Campus at Cristin Tierney Gallery What if modern masters such as Cezanne, Monet, and Corot observed subtle shifts of light and color through single-channel videos rather than oil paints? Artist Peter Campus does just that, and his videographs—a term he invented, signifying a combination of video and photography—presented by Cristin Tierney, in the far corner of Pier 94, is an Armory must-see this weekend. Summoning landscape tradition, Campus’s collection is a tribute to the wonder of the natural world, a salve for murky, disquieting times.

Based in East Patchogue (where these images are taken) and now in his 80s, Campus planned to be a painter growing up, but was introduced to video. One of the medium’s early adopters, he first worked on film sets and film editing before transitioning to his art practice. Though the work is rooted in digital manipulation and video technology—slowing his film down, accentuating certain hues— they reference the artist’s abiding interest in painting, documenting micro changes in the environment not readily perceived by the naked eye, as Monet did painting outdoors. Campus trains his focus on a fixed vantage point over time, recording the seacoast of Long Island for several hours, and then notably transforms the shoreline with panels of color that ripple and fluctuate, producing sensuous, enduring abstractions.

Sadie Barnette at Charlie James Gallery This weekend, New Yorkers have the opportunity to enter artist Sadie Barnette’s world. Recipient of the Armory’s 2019 Presents Booth Prize (for outstanding, innovative presentation), supported by Athena Art Finance, LA’s Charles James Gallery is displaying the sweeping aesthetic of Barnett’s practice, which spans drawing, photography, and sculpture to examine 21st-century identity construction.

Using pink spray paint, glitter, family Polaroids, and found objects, Barnett constructs a hybrid reality of coded, subcultural text, escapism, and resistance. Here, the 500-page FBI surveillance file kept on her father, Rodney Barnette, founder of Compton’s Black Panther Party chapter in 1968, provides the inspiration to reclaim her family’s history— a sine qua non reflection on, how in a contemporary artist’s hands, the personal is always political. Adorned with crystals, the FBI documents embody an assertion of power and survival in America’s social tableau. Armed with pink metalflake TV’s, speaker sets and crushed cans, Barnette work deconstructs race and class, enticing viewers with her glitter-scapes, but emerges as one of the most politically salient artists of today.

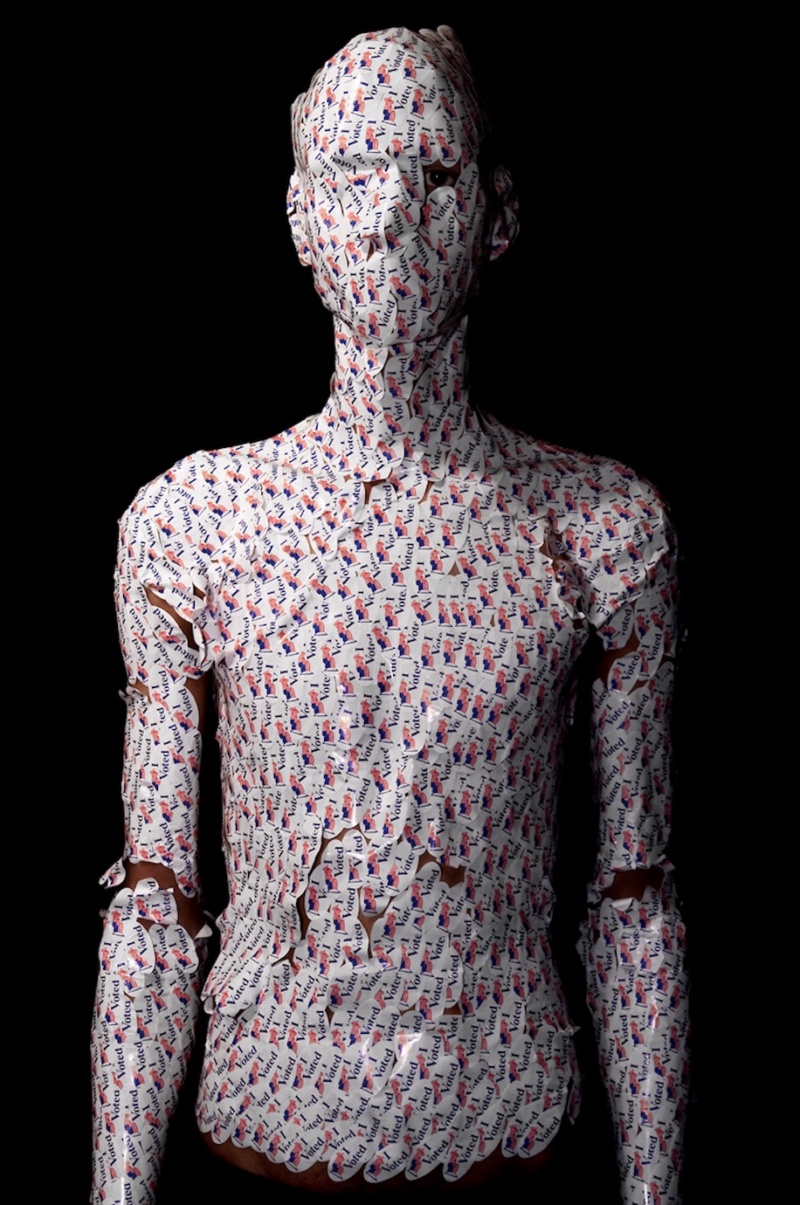

Wilmer Wilson IV at CONNERSMITH. Shy of thirty, Wilmer Wilson IV has already performed at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, as part of their IDENTIFY series, focusing on experimentation through portrayal. He’s described finding his voice through three-dimensionality, making pieces at first with Post-it notes and plastic utensils. For his sticker series—including Self Portrait as a Modern Citizen (2012)—he covers his entire body in a kind of second skin and engages in an abstract dialogue, as much with himself as the audience. Presented by DC’s Connersmith Gallery, the sculpture, Shed Skin (I Voted) (2012), is the aftermath of a New York performance in March, 2012. At the time, he described his process to The Washington Post, “I’m interested in the notion of voting politically but also voting through the actions that we make…the decisions I make— visible for everybody to see, literally.” Of course, Armory viewers will be hard pressed to distinguish the artwork from its current context, where the pile of discarded “I Voted stickers” manifests disillusionment and outrage fatigue.

in your life?

in your life?