Without a doubt, 2018 was a rich year for museum shows. Beyond just the scope of the offerings, though, there was an unmistakable feeling of change at the biggest institutions. Any year that produces the sprawling diversity of “Made in L.A. 2018” at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and puts the spotlight on Adrian Piper at the establishment pinnacle, the Museum of Modern Art, is pretty interesting. The idea of inclusion wasn’t some kind of sop or corrective to the practices of the past; it turns out that using the widest lens reveals the best work and the best stories. (Duh.)

Here are the museum shows that lingered longest and strongest in my overworked mind.

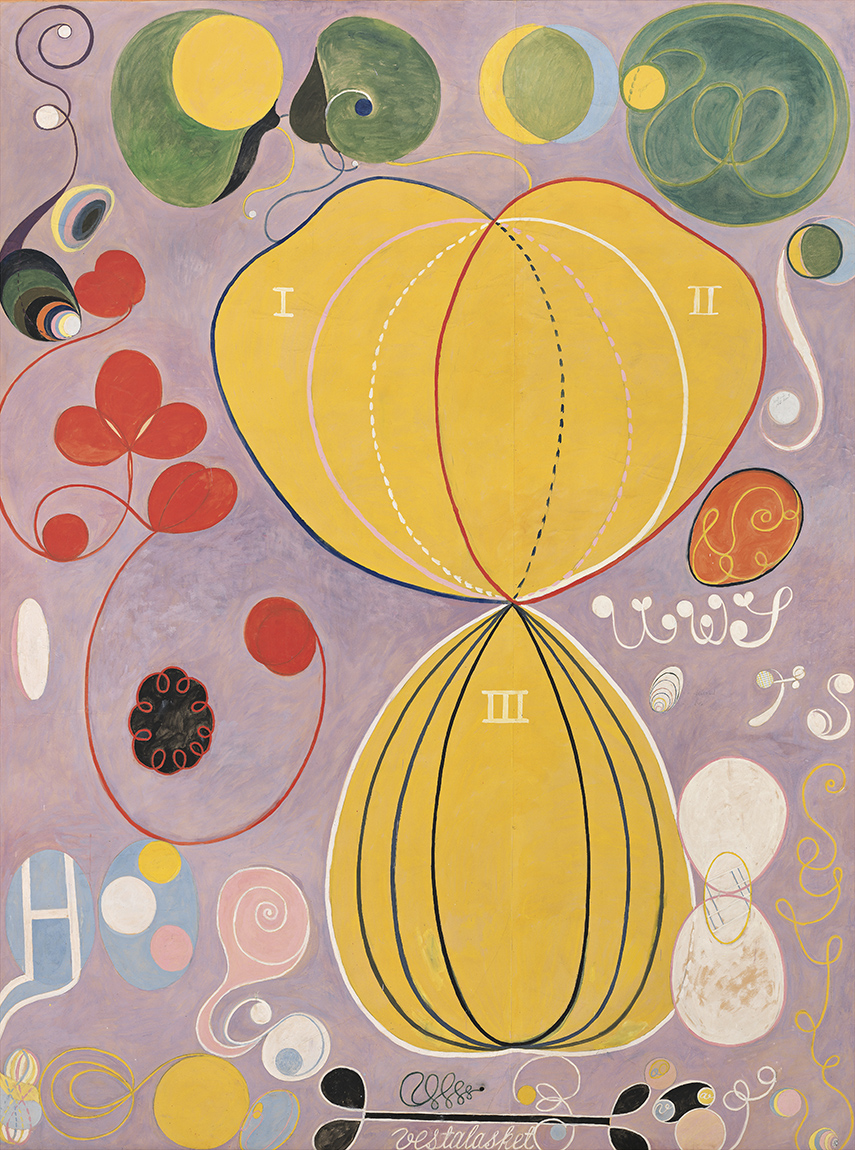

“Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” at the Guggenheim Museum You almost need the brain-exploding emoji to convey the experience of this exhibition for a lot of critics, and for the rest of us. Big, gorgeous abstract paintings by the previously unknown af Klint (1882–1944) are taking masterful control of the museum’s famed spiral, introducing us to a new body of work we can’t believe was kept from us for so long. And to learn that the Swedish artist and mystic pioneered non-representational art before the famous men of the day—including the Guggenheim’s patron saint, Kandinsky? Mind blown. Best of all, the show is up through April.

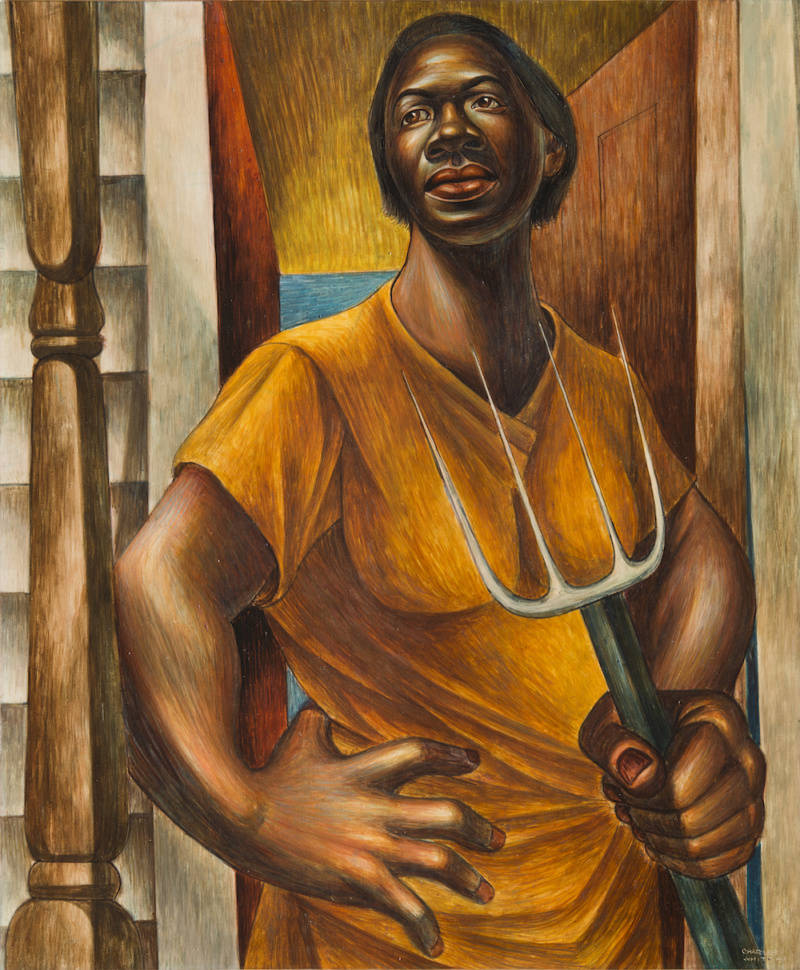

“Charles White: Retrospective” at the Art Institute of Chicago Though it moved to the Museum of Modern Art where it is on view through January 13, 2019, the show originated in White’s hometown and I’m glad I saw it there. White (1918–79) was Chicago through and through, with deep roots in the city’s black renaissance. Previously criminally underappreciated, except by a handful of fans like the painter Kerry James Marshall, White’s work got a loving and proper treatment in this show, and we could trace his development from a Thomas Hart Benton-like regionalism to his own unique Afrocentric style. He was one of the great draftsmen of his day, plain and simple.

“Rebecca Belmore: Facing the Monumental” at the Art Gallery of Ontario Belmore’s provocative Toronto show, made up of large sculptures and pointed multimedia installations, was indicative of the intense engagement with indigenous art that is characteristic of Canadian institutions (and more rarely with U.S. ones). Working with the forward-thinking curator Wanda Nanibush, who like Belmore is a member of the Anishinaabe people, the artist told stories that were both lyrical and in-your-face, with smart conceptual means. An artist at the top of her game, who will likely only get better.

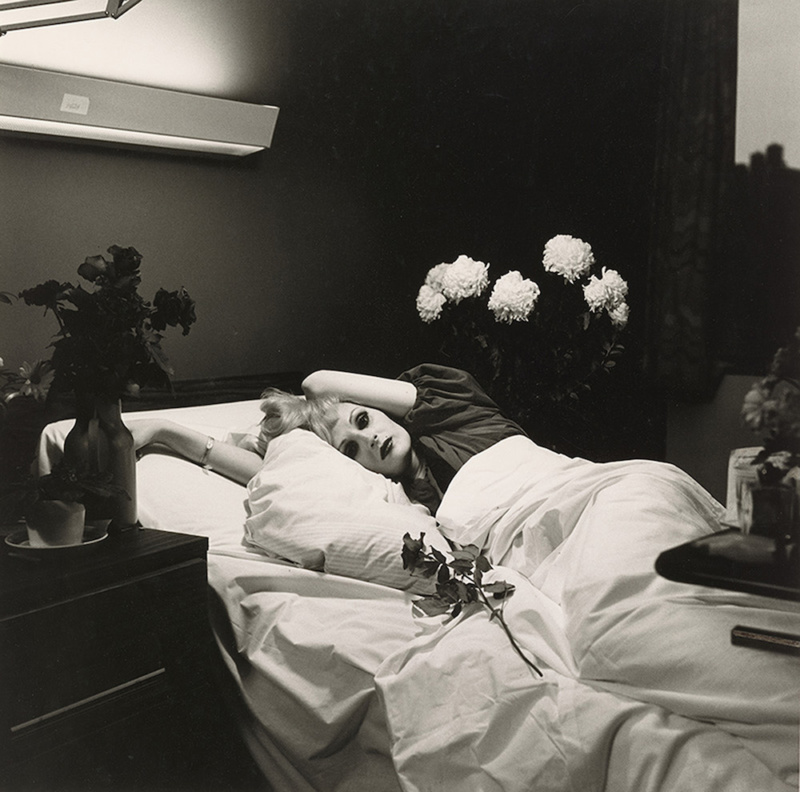

“Peter Hujar: Speed of Life” at the Morgan Library & Museum There was no better-curated show this year. The 140 photographs, arranged by the Morgan’s Joel Smith, were packed into a medium-sized gallery with the perfect pacing and sequence; we saw Hujar (1934–87) develop his eye rapidly and brilliantly. All the more devastating for the viewer when his funny, trenchant humanity and technical savvy gets cut short by AIDS (as was the case with another amazing artist featured in another great 2018 show, David Wojnarowicz at the Whitney). This show turned Hujar from a respected insider’s artist to a canonical photographer.

“Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today” at the ICA Boston The title sounds like a real eat-your-broccoli affair, but curator Eva Respini was able to talk about the internet in a way that didn’t sound you did when you explained Facebook to your grandmother in 2010. The web era is something completely new in human history that transformed everything (and quite possibly wrecked politics forever), but it’s also something we’re now totally used to and surrounds us so much we barely know it’s there. Respini’s roster of artists included Trevor Paglen, Nam June Paik, Thomas Ruff, Frances Stark and Anicka Yi—this was a thematic show with many voices that engaged and illuminated.

“Jean-Michel Basquiat” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton Maybe it’s a no-brainer to pick a Basquiat exhibition, but this massive Paris show—an athletic event spread over several floors—made an A+ artist seem somehow even more accomplished. How did Basquiat (1960–88) pack in so much art-making into the last few years of his life? And how did he learn to work at such a massive scale so quickly? For more answers, check out a version of this show coming to a new New York outpost of the Brant Foundation this spring.

“Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again” at the Whitney Museum of American Art There are whole swaths of Warhol’s work from the 1960s that I don’t feel I ever need to see again—he’s permeated the culture so thoroughly for so long. And yet, curator Donna De Salvo made him fresh again, particularly contextualizing his later years in an interesting way. And honestly, it just made me happy to see people thronging a museum show, and lining up to get in. It’s good for art.

Glenstone Technically, this contemporary art museum in suburban Maryland has existed for a few years, but the much larger addition that opened in October vaulted it into the ranks of the most significant art spaces in the country. Collectors Emily and Mitchell Rales are sitting on a massive trove of artworks by great names (the Charles Ray gallery alone astonishes), but the thing that appeals to me most about the stunning Thomas Phifer-designed addition is how personal it is. It’s quirky in places because the couple pursued their own vision of what a museum should be. And it’s free, so it doesn’t cost a dime to visit and weigh in with your own take.

in your life?

in your life?