One might reasonably expect that all has already been said about the conceptual force that is Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson. What is left to elaborate about a 25-year-long career that has garnered epic status in the art world and massive acclaim in the public realm?

Plenty, as it turns out. This season Eliasson embarks on two new ventures: presenting an exhibition, “The speed of your attention,” for Tanya Bonakdar Gallery’s Los Angeles outpost, and launching a pop-up restaurant in Reykjavík with his sister Victoria Elíasdottir, which will serve the culinary artistry of the Studio Olafur Eliasson (SOE) Kitchen. SOE Kitchen 101—as its temporary location is dubbed—provides diners with not only a sample of the food experimentation enjoyed in Eliasson’s Berlin studio cafeteria for more than a decade, but also a taste of the communal lunchtime ritual that Eliasson believes fuels his team’s creative process.

In both projects, Eliasson transcends the expectations of his audience, drawing on experts to entice viewers to use the range of their senses. “I like to say that the studio is not me; rather, the studio is next to me and we work together,” he says about his plans for “The speed of your attention.” “My process very much relies on inspiration from being among different people from different disciplines, especially scientists, and from problem-solving together.”

The breadth of Eliasson’s practice reaches beyond those of even the most socially-engaged artists. His project Little Sun, for example, founded in 2012 with engineer Frederik Ottesen, combines Eliasson’s design aesthetic with a social business model, providing small, solar-powered LED lamps and chargers to those living without reliable energy sources. In 2014, Ice Watch, a collaboration with geologist Minik Rosing, explored man’s impact on the climate by arranging 12 large blocks of ice transported from Greenland in a clock formation in central Copenhagen. Eliasson encouraged touching of the arctic sculpture, piercing the public’s conscience with a physicality that he felt graphs and data failed to provide. Ice Watch marked the publication of the UN’s Fifth Assessment report on climate change. “The issues of climate change and climate justice are more urgent now than ever before,” he told me. “I’ve been dealing with this in my work for a long time, and I believe art has the power to turn thinking into doing, and to make this crisis less cerebral and more visceral.”

Far deeper than simply participatory, much of Eliasson’s work asks visitors to engage in a self-reflexive process. Or as he’s known to describe it, to experience themselves experiencing art, witnessing the self from a third-person perspective. It is his sense of art—not merely as object or even personal encounter, but as a form of community and motivation for collective action—that governs his oeuvre. And his pop-up venture sits firmly within this paradigm. “The cooks bring everyone together each day with food,” explains Eliasson of his SOE Kitchen team. “This is incredibly important for our sense of connectedness. The kitchen staff are also doing experiments all the time, not so differently from scientists.”

Environmentalist and artist, Eliasson is preceded by his reputation as someone who creates site-responsive, full-body installations that immerse city dwellers in a spectacular artificial state of nature. In 2003, Eliasson restaged natural phenomena for London’s Tate Modern, transforming its massive Turbine Hall into a giant simulated sun, with mirrors and cloud-like formations that encouraged museumgoers to lie on the floor and bask in the “sunlight.” Shattering attendance records, The Weather Project still stands as evidence for curators that contemporary installations can be dazzling and re-orienting—both serious artistic endeavors and overwhelmingly popular tourist destinations.

Five years later, the Public Art Fund commissioned Eliasson to create a New York series, in which he constructed four manmade waterfalls along the East River. “So much of the experience of public art is how people interact with each other and the artwork,” says Public Art Fund president Susan Freedman. “These waterfalls became sources of conversation with strangers. I can’t tell you how many times I heard, ‘I’ve lived in New York City my whole life and I’ve never been on the water and seen the city from this vantage point.’” She recalls sitting in the early morning hours with Eliasson, reflecting on his intimate connection to science, art and nature. “I think The New York City Waterfalls was extraordinarily seminal for Olafur, and also for the field of public art and New York City.”

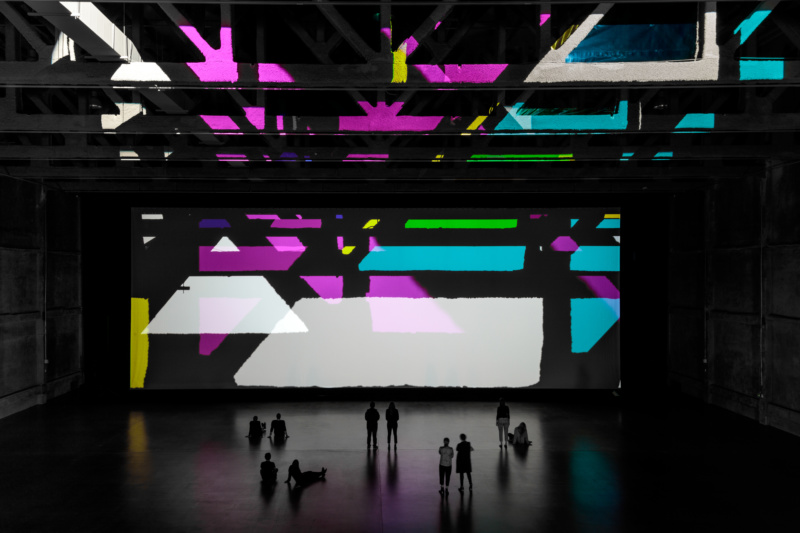

Now it’s LA’s turn. This summer, the city enjoyed its foray into Eliasson’s perceptual immersion at the Marciano Art Foundation, housed in a former Scottish Rite Masonic Temple on Wilshire Boulevard. The artist transformed the mammoth Theater Gallery into Reality projector—an architecturally-scaled, saturated-color artwork of high-intensity light beams shined through color-effect filter foils. Reality projector is Eliasson’s first piece that directly employs sound, produced in collaboration with the musician Jónsi from the Icelandic post-rock band Sigur Rós. But when asked about the auditory component and the deafening rush of water I remembered as so integral to The New York City Waterfalls, Eliasson replied: “Essentially every artwork is dependent on all of our senses, so one could say there is always an auditory element. [But] the sound of Reality projector sort of functions as a score to a film.”

Eliasson’s previous West Coast solo show was more than a decade ago in San Francisco, and there’s been a palpable void of his work in LA, according to Marciano Art Foundation deputy director Jamie Manné. “When we first encountered this building, specifically the theater space at nearly 14,000 square feet and almost 40 feet of height clearance, Olafur was actually the first artist we thought of who could handle it,” explains Manné, as we sit beneath Eliasson’s prismatic chandelier sculptures in Marciano’s ground-floor atrium. “What we really loved about his proposal was that it was devoid of any objects. The space and viewer become the artwork in a way.” Critics have described Eliasson’s art as objectless, but that’s not to say his kaleidoscopic sculpture, also shown at Marciano, are any less relevant to his practice of challenging a viewer’s notion of reality. In the fall season of Art21 viewers have the opportunity to glimpse the rigorous modeling process of Reality projector, and Eliasson describes how objects are not necessarily the most interesting part of art. “It is what the object does to me when I look at it or engage with it that is interesting,” he says. “You are provoked into a more negotiating role. Instead of questioning the object, you are questioning yourself.”

Indeed, LA provides an optimal platform for an ecologically-driven artist who mesmerizes viewers with space, light and water. This July, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery debuted its California space with LA-based Charles Long, who was simultaneously featured in the Hammer Museum’s biennial “Made in L.A.” But Eliasson’s September exhibition solidifies Bonakdar’s commitment to international artists not yet featured in the city’s exploding gallery scene.

“We felt that following up Olafur’s Marciano show made a lot of sense,” Bonakdar says. “The character of the space plays a very important role when an artist is thinking of a show. I’m quite interested to see how some of the same artists we’ve shown in New York will address this space in radically different ways.” The September exhibition, then, picks up where Reality projector left off. For instance, “The speed of your attention” features a freestanding sculpture with crystal spheres, one of the cornerstones of Olafur’s sculptural vocabulary. “The newly opened Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is very beautiful, very hospitable,” Eliasson says. “And the display of my work interacts with and depends on the minimal space.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more

in your life?

in your life?