One imagines that when the Metropolitan Museum of Art selected Huma Bhabha for its Cantor Roof Garden commission, the institution did so because the artist’s concerns chime so eloquently with the issues of our times. That is what I take Shanay Jhaveri, assistant curator of South Asian art at the Met, to mean when he cites “the political exigency” of Bhabha’s sculptures. “Her work has always confronted the notion of cultural otherness, elliptically, obliquely, but it is there,” says Jhaveri.

She certainly fits the bill. As a woman born in Karachi, Pakistan who came to the States to study at the Rhode Island School of Design and has lived here for several decades, Bhabha brings a particularly global perspective to her artistic practice. Her work for the Met, Bhabha tells me, continues in the idiom for which she’s best known, and it would seem to have a slyly topical resonance. That the exhibition, which opens on April 17, deals with migration, disenfranchisement, visitors from other places—perhaps even other worlds—can be gleaned from its title, “We Come In Peace.”

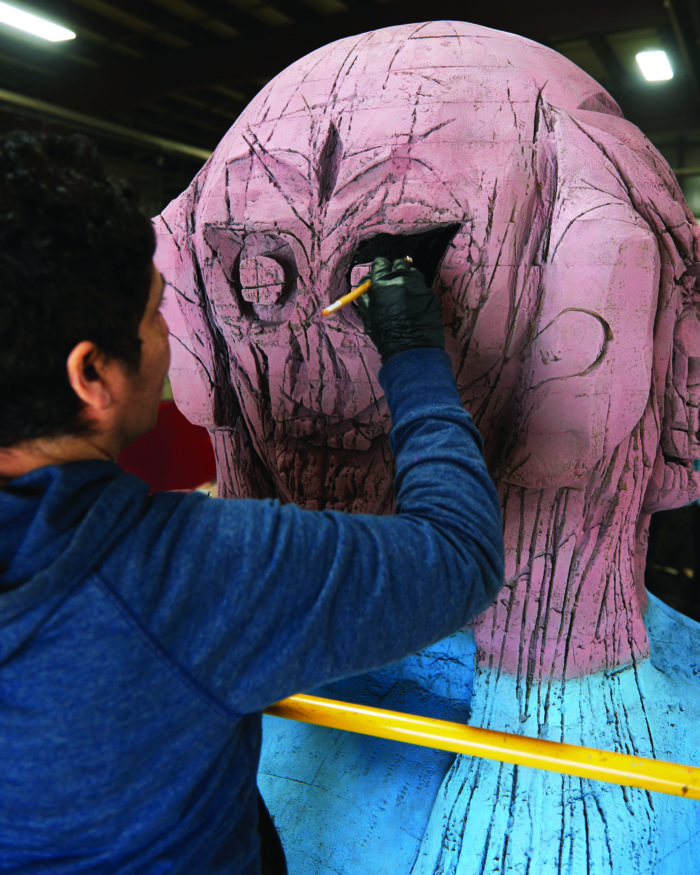

“There’s an element of theatricality in the way I display my work,” says Bhabha. “I thought about the roof as a landing pad for visitors from somewhere else.” It will be populated by two monumental bronze sculptures, one standing about 12 feet tall, the other a horizontally oriented piece some 17 feet long. Figurative without being strictly representational, her sculptures have tended to be made primarily from Styrofoam and cork but also utilize plastic, clay and wood. The bronze pieces for the Met have been cast from originals composed of these less traditional materials.

For all its contemporary relevance, Bhabha’s work stands out from much of today’s art for something much more old-fashioned: a commitment to imagination, to creating something new by learning from historical examples and for an aversion to theoretical justifications. “As a rule,” she says, “I don’t like work that has to go with text.”

She counts Picasso and Rauschenberg as among her strongest influences, though her range of reference extends from the totems of the northwestern Native Americans to African sculpture to dog calendars and science fiction films.

On the day I visit, several cork pieces stand in groups in the Poughkeepsie, New York studio that takes up the ground floor of an old firehouse, where she lives with her husband, Jason Fox, and two large, frisky dogs. There are hatchets for hacking at cork, chisels and other tools, a pile of blue Styrofoam, blocks of wood, stacks of works on paper. Unlike many of her colleagues, Bhabha prefers to commune with her subjects alone, without the aid of assistants.

She thinks of the sculptures—which more often than not stand vertically, like humanoids or totems—as characters. They are neither male nor female but hermaphrodites whose personalities, or spirits, she discovers in making them, first by roughing out sketches, then by hewing into the material. Rather than conveying a concept, she hopes they radiate intensity.

“I’m not interested in appropriation. I’m much more interested in being imaginative and creative. But, of course, I’m highly influenced by looking at stuff. There are references in the work to things I have seen, if you know enough art history. It’s about understanding why certain things were done, how through the ages people from certain cultures influenced each other because of crossing over, visitation,” explains Bhabha. “For example, you see influences within Greek sculpture of Hindu sculpture because of their proximity and trade.” Indeed, the other aspect of her work that recommended it to the Met was, Jhaveri told me, the way it “engages with an entire history of figurative sculpture.”

Bhabha’s is an idiosyncratic and analog approach. She doesn’t even scour the Internet for the images that she at times embeds in her sculptures and that also serve as the grounds of her works on paper, preferring to take photographs herself or to snip them from old magazines and calendars. The kinds of things people cull online are, she explains, too homogenous, and, I suspect, too impersonal.

Still, for all her serious absorption in the history of art, and the ancient look of her pieces, Bhabha can be quite humorous. Who else would top a tribal-looking totem with a Styrofoam face? Or, for that matter, turn the Met roof into a landing zone for space aliens?

Bhabha moved to Poughkeepsie 15 years ago because she couldn’t afford to continue living in New York City. Yet her unique sensibility, which in the space of one work might swivel from Mesopotamia to marijuana, has now made her one of the most in- demand artists on the planet. In fact, the Met show is only one of three that opening this month: “With a Trace” commences at her New York gallery, Salon 94, on April 22, while another will debut on April 27 at Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin.

Is the crush of shows exciting or daunting, I ask her. The former, she says. “I’ve worked a long time to have an opportunity like this.”

in your life?

in your life?