At The Broad, time is a small price to pay for an existential experience. After a mere two- or three-hour wait, visitors are given the opportunity to step through an ordinary door into an kaleidoscopic abyss, a few dozen strings of colored, hanging LEDs multiplied into millions by the mirrored walls and shallow reflecting pool on the floor. This cosmic voyage into the twinkling unknown lasts a total of 45 seconds, enough time to snap a few selfies, and then it’s someone else’s turn.

This is the “Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away” by Yayoi Kusama, a prolific 87-year-old artist who, despite having lived in a Tokyo mental hospital since 1977, is still actively making work in her studio across the street. Hers is one of The Broad’s most popular exhibits and a culmination of her lifelong obsession with the infinite, our own atomic particles, and overcoming the obstacles of her mental health.

Kusama was born in rural Matsumoto, Japan, in 1929, and as a young girl suffered from both domestic abuse and aural and visual hallucinations. “So many different images leaped into my eyes that I was left dazzled and dumbfounded,” she said in a 2012 interview with the Financial Times, and through art she found solace. Her fixation with infinity showed in early paintings of dots, or the small arches arranged into her rippling “Infinity Nets.” Her 50- to 60-hour-long marathon painting sessions were driven, she’s said, by a “compulsion to realize in visible form the repetitive image inside of me.” In sculpture, the dots manifested themselves as phallic protrusions, stuffed fabric cones that colonized the surfaces of sofas, chairs, and a 10-person dining table. In her 1965 installation “Phalli’s Field,” she surrounded a carpet of red polka-dotted phallic shapes with mirrored walls, cutting down the physical labor her pursuit of infinity, and the first Infinity Room was born.

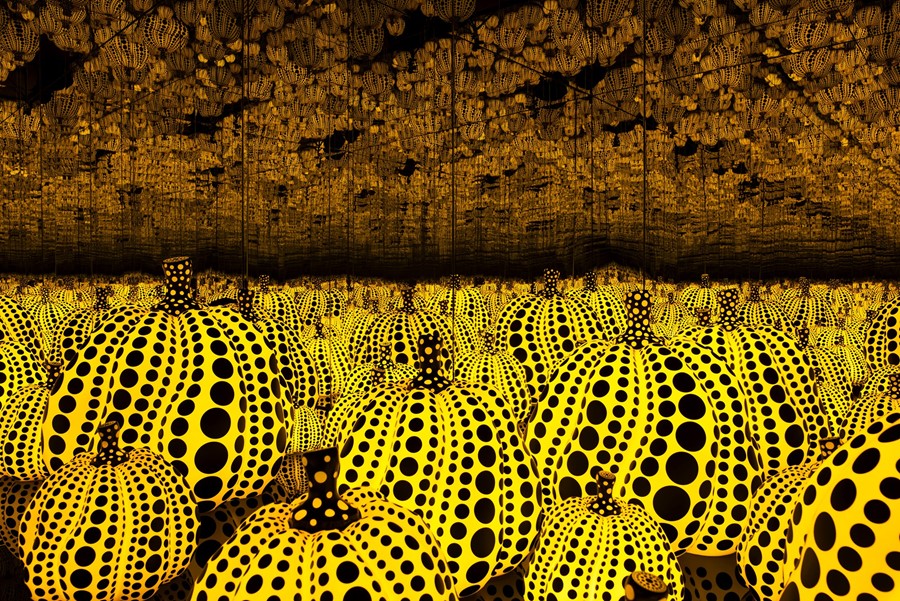

At its inception, the Infinity Room broke new ground in Relational Aesthetics, art that relies on the participation of the viewer. Five decades and 20 Infinity Rooms later— some with disco-colored lightbulbs, others with luminous pumpkins or silver, reflective balls—they’re nothing short of a “cultural phenomenon,” says Broad director Joanne Heyler. In October, the museum welcomes “Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Rooms,” an exhibition that, during its original three-month run at The Hirshhorn, drew 475,000 visitors, twice the museum’s average for that time of year. They waited in infinite lines for seemingly infinite hours and produced infinite selfies, or, by the museum’s count, 34,000 Instagram posts.

The traveling exhibition features six Infinity Rooms, as well as Kusama’s “Obliteration Room,” a household-themed space that’s all white until visitors have covered every inch with stickers of colorful dots. Our best advice to experience her work at The Broad is to arrive early—there’s no telling how long the wait for this one will be. Those in New York can cut the line and see Kusama’s Net paintings at 101 Spring Street or in Chelsea at David Zwirner‘s upcoming show.

in your life?

in your life?