Growing up between San Francisco and Southern California, Mary Heilmann remembers being packed into her parents’ car for innumerable road trips up and down the West Coast. She went on to college at U.C. Santa Barbara, then graduate school at Berkeley. Once she finished, in 1968, Heilmann was ready for a change of scenery. Leaving the idyllic California landscape behind, she headed to New York, where a new breed of artist was flourishing Downtown amid dingy buildings and dark bars. Far from the hesitant type, Heilmann would strike up conversations with art stars like Keith Sonnier and Robert Smithson, determined to make her mark on the art world.

Among the artists she admired most, but never met, was Dan Flavin. “He was like a god to me,” she says.

She had learned of Flavin’s work while studying sculpture and ceramics as a graduate student. “It got my attention, because it was a pretty interesting way to think about doing sculpture: Plugging in a lamp,” she says.

This summer, Heilmann’s long-held esteem for the artist will come full circle, in the form of a show at the Dan Flavin Art Institute in Bridgehampton, New York. The survey will feature work made since the ’70s, overall underlining the significance of the venue to Heilmann. Of the several new pieces to be included, two paintings each deliberately reference a sculpture from Flavin’s Icon series that appeared in the exhibition prior, and will be hung in the same place on the wall.

The Dan Flavin Art Institute opened in 1983, and Heilmann began visiting the area more and more frequently as the decade progressed. One of the works in the show, Rio Nido (1987), was painted in a rental around the corner from the Institute during an extended stay. She finally moved her main studio from her Tribeca loft to Bridgehampton in 1999. “I can meditate and concentrate on the work,” she says. “There’s more quiet and solitude.” Visits to the city are for “things that require more input from other people.”

As those who know her will attest, Heilmann prefers to make her art in relative isolation.

“We live with this Judeo-Christian work ethic, where it seems like the solution is just do more,” says the artist Marilyn Minter, who has been a close friend since the mid-’80s. “Mary always knows when to stop. The hardest thing there is to do is to learn how to stop, how to not overwork.”

Back in 1977, curator Alanna Heiss invited Heillman to participate in “A Painting Show,” which was a large group show at the newly founded space, now known as MoMA PS1. It was the first of several projects they would work on together, including a large mural Heilmann created two decades later for “Vertical Painting Show.” “Her colors were very strong, she was very abstract,” says Heiss, noting that her work didn’t align with another group or style. “She was always very independent, refusing any kind of gang pathology,” Heiss recalls, even with the “incestuous” nature of the ’70s art community.

Describing her experiences as a young adult, Heilmann speaks fondly of circumstances in which she could play the contrarian. At Berkeley, she says, “It became part of the deal to try and be avant-garde and shock the conservative professors.”

Early on in New York, her mere presence in the art world was an anomaly. “It was all men. My role models were men. I liked the fact that I was one of the only girls.”

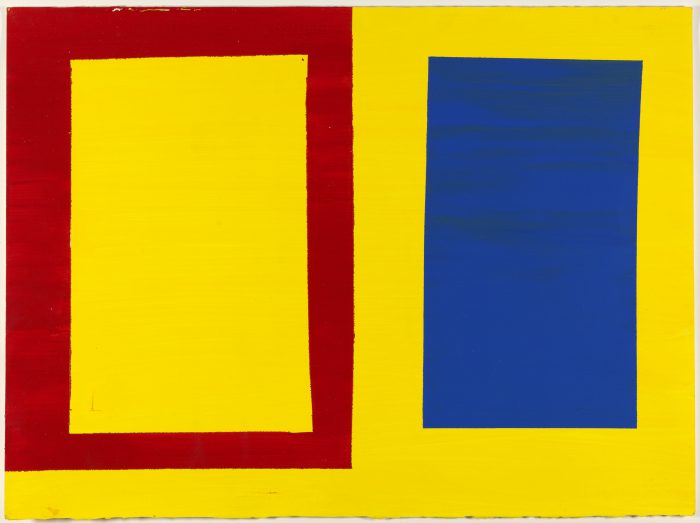

In the following years, of course, Heilmann erased any doubts as to whether her novelty as an artist extended beyond her femininity. To wit, she will be the subject of another show this summer, at New York’s Craig F. Starr Gallery. In “RYB: Mary Heilmann Paintings, 1975-78,” the exhibition in July will bring together some of the artist’s most seminal works, marking the first time in 40 years the Red, Yellow, Blue paintings have been shown together.

in your life?

in your life?