A conversation with the artist Raymond Pettibon is a master class in ellipses. There are breaks, fits and starts, and halting gaps. This is a man with a lot on his mind, and he’s in no rush to communicate it all. To talk to him, you have to slow your metabolism and get into his groove.

“Everything here is a work in progress,” says Pettibon, 59, who appears to be wearing pajama bottoms for the workday in his SoHo studio. He’s a philosopher-king who manages to combine grumpy world-weariness with a completely open mind.

A long pause ensues. Traffic noises waft in from the street below.

“I don’t have any idea how it will all play out,” he finally says.

To get into the topic at hand—his big survey show at the New Museum, “Raymond Pettibon: A Pen of All Work,” through April 9—you have to go sideways, since this artist always has something uncanny in his peripheral vision.

A good start is a stroll through the studio, which is positively littered with drawings in various states of completion. There are a lot of books lining the walls too, some holding down the corners of drawings lying on the floor. Serious art criticism, volumes of Romantic poetry and comics are all part of the literary mix.

There’s a basketball hoop and backboard, since Pettibon loves to play the sport, though he’s blown out his knee doing it. On a high shelf is a series of paintings by other people, from thrift-store finds to works by Henry Rollins and the Big Eyes artist, Margaret Keane.

Pettibon stops in front of his own most prominent work-in-progress: his black-ink version of James McNeill Whistler’s “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1,” a.k.a. Whistler’s Mother, which is tacked up on the wall. He has reimagined the iconic work with sweeping black lines, and it seems to be taking flight on the bottom, though mom’s face is more faithfully rendered in smaller strokes.

Pettibon’s knowledge of art is deep, and he can discourse at length on the famous feud between Whistler and critic John Ruskin—not only can he quote from their fracas, he can tie it to the development of abstraction in the 19th century beginning with the misty canvases of Joseph Mallord William Turner. He sees the big picture.

More than just a rote knowledge of history though, he has utterly absorbed the visual lessons. “The original is a great painting, but it is a painting,” he says. “If you look at Whistler’s drawings and etchings, that’s cross-hatching at its finest. So I made this an exercise in cross-hatching….Cross-hatching itself is sometimes a subject for me. It’s not just a means to represent something.”

Draughtsmanship—both its execution and as a meta-topic for exploration—is key to Pettibon’s work, and that’s why the New Museum show features more than 800 drawings from his decades-long career.

Even so, Pettibon says of drawing, “It’s something I struggle with.”

Though he has a waterfall of ideas every day—“enough for many lifetimes,” he says—getting them into the world is a painstaking process for Pettibon. Like his speech, it takes time and he won’t be rushed.

“Many artists get to a certain comfort level with their work,” he says, with only a brief lull before the next sentence. “And they stay there forever. Every time I start a new work, it’s starting from the beginning.”

His personal beginnings trace to the Los Angeles area, where he grew up the son of novelist, R.C.K. Ginn, so writing has always been a part of Pettibon’s own work, too. His brother Greg Ginn founded the punk band Black Flag, which included Henry Rollins. Pettibon played in it for a time, and most famously designed its four-black-bar logo, an iconic image whose prominence caused him some chagrin in the years since.

“When it’s on your Wikipedia page, it’s your legacy ’til the day you die,” he says calmly. “It’s absurd. But it’s not for me to wish it away. Then you’re trying to cover it up.” (He adds a historical fun fact: “The punks hated me.”)

The look of Pettibon’s work certainly shows that he has assimilated the visual lessons of comics too, which have been a shaping force for many artists over the years. “In the most obvious way they have been a huge influence graphically,” he says, but he was never the classic nerd. “I love the medium, but I’m not a fan of comics fandom.”

They helped him learn to draw and to “combine words and image,” he says. “It’s the sequential story.” But of course, Pettibon went his own way with the look of comics, eschewing obvious heroes and villains and complicating anything easy and safe with trenchant but ambiguous forays into religion, politics and other messy topics.

“I am not so much interested in narratives with a beginning and end,” he says. Visually, he also broke with the clean, straight lines of comics, imparting a painterly panache and brushstrokes that sometimes recall the great canvases of the past.

There’s not really a string of three or four most famous Pettibon works to cite that would explain his trajectory since he came to prominence in the late ’80s—you need to sit down with an accumulation of many pieces to accrete meaning.

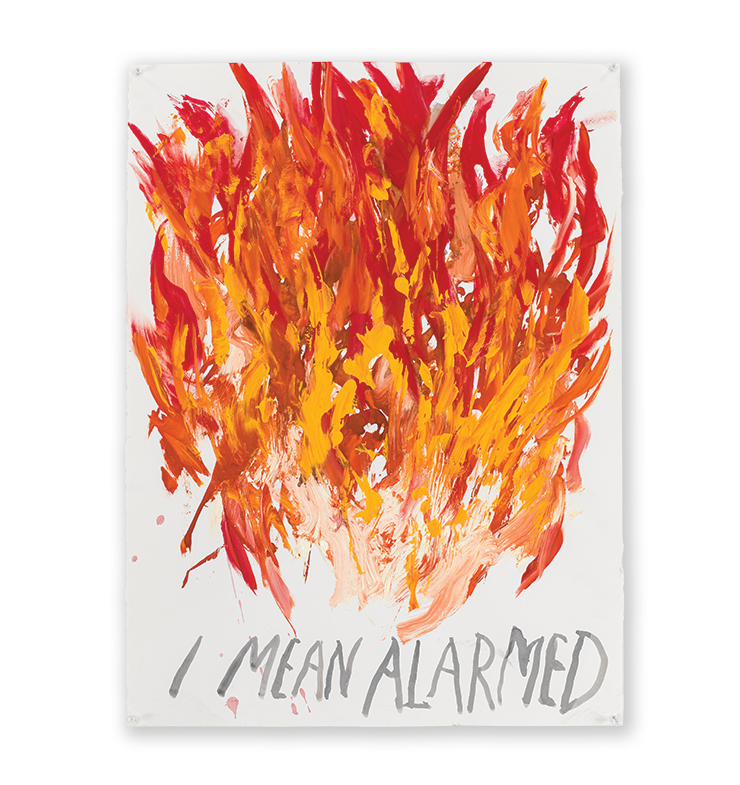

That’s why the handsome and definitive 2016 book “Raymond Pettibon: Homo Americanus,” published by his gallery, David Zwirner, is valuable as a force multiplier. You can see the evolution from “Captive Chains” (1978), a comics-esque foray that also channels Goya, to works of the 2010s that include bright colors, which became more prominent in his work in the last decade.

Not that Pettibon is sitting around reminiscing about the past a lot. “I don’t dwell on my old work—not that it scares me and I never want to look at it again,” he says. “It’s part of me.”

This is an artist who has achieved major clout in the marketplace, but for him, the spoils of success (money, having a big exhibition) simply mean having the ability to determine his own fate.“I love people who appreciate my work,” Pettibon says. “The galleries, the fans, the readers, the viewers. I’m not working in a vacuum. But there’s not that call and response—no back and forth, testing the market. That kind of independence I’m glad I have, and that would be hard to give up.”

We’ve finally found a topic that involves no hesitation from Pettibon. “I’m in a position of doing what I want to do,” he says. “I have the blank piece of paper and my instruments at hand, and that’s all I have to answer for.”

in your life?

in your life?