Trawling the booths inside The Barker Hangar during the recent Art Los Angeles Contemporary fair, there appeared to be a quiet desperation among some dealers who seemed a bit nervous about their prospects. This wasn’t the case, however, at a petite slip occupied by Mier gallery, Nino Mier’s new West Hollywood space, which sold out its entire suite of Surrealist portraits by a relatively unknown Swiss-born artist named Louise Bonnet within the first hour.

“Louise who?” or, “You know, the paintings with the big phallic noses?” or, “Oh, she’s Adam Silverman’s wife,” were just a few of the whispers overheard among the hoi polloi, and you couldn’t really blame them. See, Bonnet has toiled in the shadows for more than two decades, but that’s all about to change very soon.

Some of Bonnet’s recent work hangs inside her and Silverman’s Los Angeles home, including The Grab, 2016, The Tennis Ball, 2016 and The Rope Vest, 2015. Photo by François Dischinger.

Some of Bonnet’s recent work hangs inside her and Silverman’s Los Angeles home, including The Grab, 2016, The Tennis Ball, 2016 and The Rope Vest, 2015. Photo by François Dischinger.

After studying illustration and graphic design at the Geneva University of Art and Design in Switzerland, Bonnet moved to Los Angeles in 1994 with the intention of maybe staying one year. “I could live with some friends and speak French to their kids and sort of be this au pair,” the artists recalls over cookies and coffee inside her voluminous Atwater Village painting studio, where she has been steadily working for the past 15 years. Bonnet used to share the space with her husband and his ceramic outfit, Atwater Pottery. A year after she arrived in the States, Bonnet took a design job with Silverman’s former streetwear company, X-Large. After a couple years she left the company, kept Silverman, and all the while continued to paint.

“My work back then was very graphic,” says Bonnet, who rendered characters from classic films (The Shining, Carrie, Le Mépris, A Clockwork Orange) and produced a series of works featuring Yoko Ono in a style evocative of Alex Katz or David Hockney, though the artist cites Robert Crumb and Picasso as her real influences. The early film portraits caught the eye of Shepard Fairey, who exhibited them in his L.A. gallery, Subliminal Projects, in 2008, while the Yoko paintings debuted at No. 12 Gallery in Tokyo one year later. “We didn’t have a TV when I was growing up, so I invented characters to entertain myself.”

Bonnet’s The Tennis Ball, 2016.

Bonnet’s The Tennis Ball, 2016.

Yet while Silverman was becoming an acclaimed potter with exhibitions across the globe, and stepping into the director role of Heath Ceramics, Bonnet was effectively rendered a Sunday painter, selling works to her friends until the fall of 2013. “When my son started preschool I could have a whole day,” says Bonnet, a mother of two. She gave up acrylic-on-paper for oil-on-canvas after her friend artist Ricky Swallow suggested she try the classical medium. “Oil changed everything,” she adds. Though perhaps the biggest revelation was Bonnet’s decision to stop using reference images and overthinking how the final image would look in favor of just “being loose.” “I was going to start making the thing before I could worry about it or wonder what it was,” explains Bonnet, who made hundreds of sketches over a six month period in an attempt to create “a new face.”

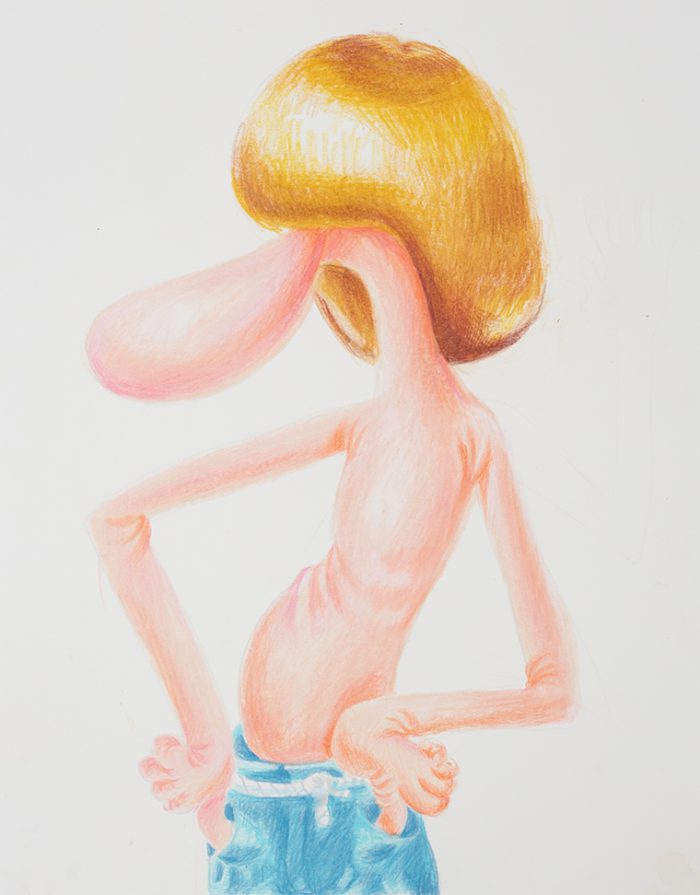

For her latest outing, at ALAC, Bonnet’s work took a serious turn: characters wearing athletic outfits befitting country club or Olympic settings, marked by flaxen shags, dangling or swooping proboscises, and accordion limbs that evoke bendy straws and rubber hoses. Rather than painting to create a specific figure, Bonnet created figures to facilitate specific actions such as a bulbous magenta finger pushing a shoulder or a bloated hand slapping a face.

“I like the implements or the tools more than the figures, like if you’re an ice skater you have to wear these clothes that are ridiculous but they look very serious,” says Bonnet, whose hang-nose painting of an ice skater was a sensation at the fair. “The figures make some people uncomfortable maybe because the noses look like penises, but I don’t start out thinking I’m going to paint penises. I just like when things go in and out of something.”

While some critics have compared her figures to French cartoons, she insists that they are less a product of humor and more the brainchild of horror movies and the disco-era photography of Ron Galella. “It’s a lot of movement that’s frozen and sculptural, these people dancing and walking really fast, doing something that looks so stupid when it’s frozen. I like giving way too much attention to a gesture that’s not even important,” says Bonnet. Pointing to the gyrations of Studio 54 habitués captured in Galella’s “Disco Years” monograph, she adds, “When else would you look like this? Doing something like this?”

Bonnet’s attention to seemingly mundane details—and her ability to introduce a new type of figure into the contemporary painting landscape along the lines of Jonathan Gardner or Ella Kruglyanskaya—has turned her into an in-demand artist with waiting lists for her work. “I just wanted to make enough money so I didn’t have to get another job,” admits Bonnet, who sold the first three dozen of her new works to close friends.

She was genuinely worried about justifying her studio rent if her fortunes didn’t change until Sprüth Magers’ L.A. director, Sarah Watson, showed an Instagram photo of a painting to Hollywood gallerist Mier one late night last summer. Though it took him a week to convince Bonnet to meet with him—“I thought, Oh, no, she’s going to be one of these difficult artists,” jokes Mier—he has since sold 15 of her paintings and the half-dozen in her April solo debut at his gallery are already promised to an impressive roster of Hollywood machers and museum trustees. She also has a new portrait—a tube-nosed woman being pelted by tumescent orbs of water in a shower while wearing a bathing suit and cap that covers her eyes (The Swimmer) —in a group show at Berlin’s König Galerie alongside works by Gardner, Michael Williams and Sanya Kantarovsky. “It’s a little scary,” says Bonnet of her newfound success. “But this is what I always wanted. Just to, on some level, have the ability to be a working artist.”

in your life?

in your life?