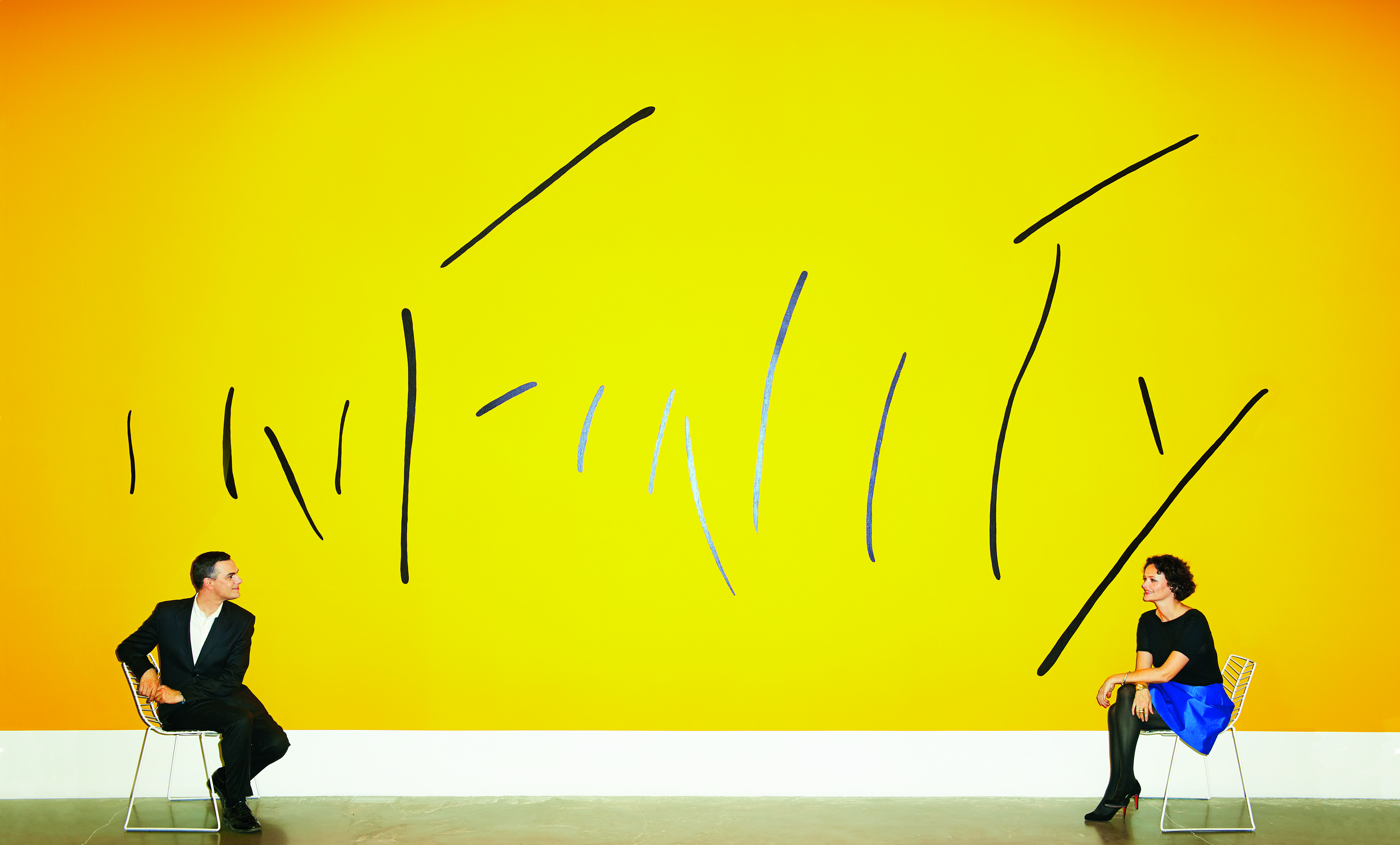

Massimiliano Gioni, wearing Trussardi, and Cecilia Alemani seated in front of Tributes to Kusama: Infinity, by Jessica Diamond circa 1992/3 from the Luigi Polla collection at the New Museum. Photography by

It’s shaping up to be a monumental year for New York art-world dynamos Cecilia Alemani and Massimiliano Gioni. Their day jobs are impressive enough: Alemani, 36, is curator and director of the expansive public art program at the High Line, the elevated park along Manhattan’s West Side. Gioni, 39, is associate director and director of exhibitions at the New Museum, as well as artistic director of Milan’s Fondazione Nicola Trussardi (of fashion-house repute).But this summer, the transplanted Italians, married since 2011, are stepping into an even brighter spotlight. Alemani just reprised her role as curator of the Frieze Projects, a program of commissioned artworks at the Frieze New York fair on Randall’s Island in May. And in June, Gioni makes his debut as the youngest director in the 118-year history of the Venice Biennale (through November 24). “There are so many expectations, from the outside as well as from myself,” admits Gioni of the microscope that will surely focus on his leadership of the granddaddy of all biennial art shows. “Everyone is looking at it with different eyes.”

Art is a family business for Gioni and Alemani, who prefer visiting mu- seums and galleries as a team and engage in constant dialogue about their respective projects during off-hours. “When we’re home, we talk about work all the time, which is also a pleasure,” says Alemani, “because it’s art; it’s what we love.” (Although they have collaborated professionally in the past, they’ve decided it’s healthier for the relationship to keep their projects separate.) In fact, they are so fully in tune with each other’s work that they elect to switch roles during an interview—letting one spouse introduce the other’s curatorial ideas for a journalist visiting the couple’s new apartment on St. Mark’s Place, in Manhattan’s East Village. It’s evidence of a tangible playfulness between the partners, both of whom are easygoing, energetic and quick to laugh—perhaps not what one might expect from a pair of accomplished art-world wunderkinds. They seem perfectly com- patible in temperament and appearance: Alemani, pixieish and sparkly with bouncy brown curls, wears silver-studded black wingtips, a variation on the plain black wingtips worn by Gioni, who has expressive brown eyes and a distinguished, if premature, touch of gray at the temples.

Their playful personalities aside, Gioni and Alemani are serious about work and rigorous in their research. Gioni’s ambitious concept for the Venice Biennale, titled “The Encyclopedic Palace,” was inspired by the vision of Italian-born, Pennsylvania-based outsider artist Marino Auriti for an imaginary museum that would house the entirety of worldly knowledge and human discovery. Executed in the 1950s as a massive architectural model, Auriti’s theoretical “Encyclopedic Palace of the World” was a colossal structure, with a tiered, 136-story skyscraper rising above a neoclassical base that would cover 16 blocks in Washington, D.C. “It’s a show about obsessions and the transformative power of the imagination,” says Gioni, “and about artists or individuals who somehow have tried to describe or get to know everything.” Indeed, flights of fancy fill the show—from Athens-based Christiana Soulou’s interpretations of imaginary beings conjured by famed writer Jorge Luis Borges to Colombia’s José Antonio Suárez Londoño’s visual translations of Kafka’s diaries.

Two of the more novel aspects of the Biennale under Gioni’s direction are the inclusion of artists who are “not exactly professional artists,” as he puts it (including self-taught artists like Auriti and James Castle), and major art-historical figures from the 20th century, whom Gioni sees as underappreciated or, at minimum, non-canonical. “We’ll see when the show opens if it’s controversial, but it’s definitely slightly polemical about what is art, who is an artist, and why we expect a certain celebration of a certain type of artist,” the curator explains. “We wanted to open those discussions up a bit more.” Perhaps to take attention from his own youth, Gioni has embraced older artists among the 158 in the Biennale, including 82-year-old Arte Povera member Marisa Merz and 93-year-old painter Maria Lassnig, a grande dame of Austrian art.

In her curatorial role at Frieze Projects, meanwhile, Alemani looked at least partly to the past, with a re-creation of FOOD, the iconic New York restaurant launched by artists Carol Goodden and Gordon Matta-Clark in 1970s SoHo. Some of the original FOOD chefs, joined by present-day artists, made the temporary eatery an interactive melting pot of art and cuisine. But the rest of Alemani’s Frieze program focused on installations by emerging artists: Liz Glynn, Maria Loboda, Andra Ursuta, Marianne Vitale and Mateo Tannatt, the only male among the group (the almost-all-female lineup was pure coincidence, says Alemani). Although Frieze is a high-profile affair, Alemani much prefers reaching the kind of broad audience—4.4 mil- lion visitors last year alone—that gets to enjoy the public artwork she com- missions for the High Line, which is typically on view for a year versus the four days of Frieze.

This summer, Alemani commissioned Swiss-born New York artist Carol Bove to create an ambitious installation. Titled Caterpillar, the series of large-scale sculptures populate the still-wild landscape of the High Line’s third and final phase, due to open in stages next year. Alemani will also continue to lead programming for the art-intensive elevated park, including performances, video installations and a popular, ever-changing piece that occupies a billboard on 10th Avenue, alongside the former rail line. The Venice Biennale will be well under way by then, and the couple’s personal and professional lives will resume a more normal—but still energetic— pace. As Alemani says of their post-Biennale future: “It’s going to be a new beginning.”

in your life?

in your life?