Oversize power suits, uptown steakhouses, misbehavior at star-studded centennials, caviar in uncalled-for situations, glitzy memoirs about expense accounts and black cars: This spring, the ’80s are back.

The writer Sean Monahan dubbed the trend “boom boom,” defined as “a pure expression of excess” centering “male-coded values.” The New York Times described it as an embrace “by fashion labels, influencers and ordinary spenders, of lavish old-money consumption.” The recent American Psycho reboot announcement is almost too on the nose.

Against the backdrop of recession threats and an ’80s Don with (in)famously tacky taste and a predilection for political evil (boom boom as in bombs) sitting in the Oval Office, the aesthetic inspires queasy inquiries as often as nihilistic glibness. People are clearly hungry for explorations of the trend, if attendance at various boom boom-coded events in April are any indication.

On Tax Day, hundreds braved six flights of stairs to an Elizabeth Street loft to hear a ragtag crew—including venture capitalist Brad Burnham, the financial journalist David Carey, and Corissa Steiner, a self-proclaimed “fired for attitude” former Wall Street financier turned hypnotist and investor—explore “the crossroads of finance and culture.” The following week, it was standing room only at the Soho bar Sloane’s at The Manner for the first iteration of Fashion Fiction, a new reading series from Mikaela Dery featuring “fashion writing from past and present.”

The Tax Day reading took a tongue-in-cheek tenor (there was a land acknowledgment that we were on “Blackstone-owned land”) while the ambiance at The Manner had a vibe of severe luxury (think: marble fireplace, vaguely orientalist wall art, and towering PR girls with a guest list written in font so tiny I wondered if they had been given super-advanced experimental Lasik).

The readings approached fashion at angles ranging from the affectionately critical to witheringly satirical. Author Natasha Stagg read from industry insider Elizabeth Hawes’s 1937 book Fashion Is Spinach, a razor-sharp look at the clothing business, while New Yorker writer Judith Thurman excerpted her 2014 profile of the cult Japanese designer Rei Kawakubo.

The Times recently reported a rising plague of “money dysmorphia” among youth who are spending beyond their means. The term’s roots in body dysmorphia are worth noting, given the fashion industry’s current rejection of body diversity in favor of Ozempic-aided emaciation. Perhaps boom boom’s imagined businessman is the big-spending answer to the prayers of the Bimbos and Tradwives who dominated TikTok last year. Yet while the line between complicity and camp might be blurry, it is still discernible, and for every earnest acolyte of the C-suite, there’s a languid leftist wearing their version of this season’s Stella McCartney collection “laptop to lapdance” with a wink. As Emilia Petrarca noted, “we’re already seeing boom boom used and subverted by queer artists.”

The executive eyeing a bimbo at the bar before heading home to his tradwife might seem like a story too obvious to overinterpret, but it’s often the most archetypal of fables that lend themselves to the most inventive retellings. This April, the play Becoming Eve pulled off just such a spectacular reinterpretation of—if not the oldest story in the book—one of the oldest stories in one of the oldest books, namely, the Old Testament.

Deftly adapted with precise wit and a spritely poetic cadence by playwright Emil Weinstein from Abby Chava Stein’s memoir of the same name, about coming out as trans and leaving her Hasidic community, the play pivots on an ingeniously zany interpretation of the Akeda, the biblical story of Abraham’s almost-sacrifice of his son Isaac. The show, which closed last week at the Abrons Arts Center, stars the actor Tommy Dorfman fresh off her dual role as Nurse and Tybalt in the star-studded reworking of Romeo and Juliet on Broadway.

Becoming Eve takes place over the course of one conversation and an entire life, as Chava comes out as a trans woman to her Hasidic father while recalling her religious upbringing (in a poignant twist, puppets depict the youthful versions of Chava). Weinstein’s writing brings compassionate curiosity, high-octane analysis, and crystalline grace to a story that could easily have been a trite tale featuring stock characters.

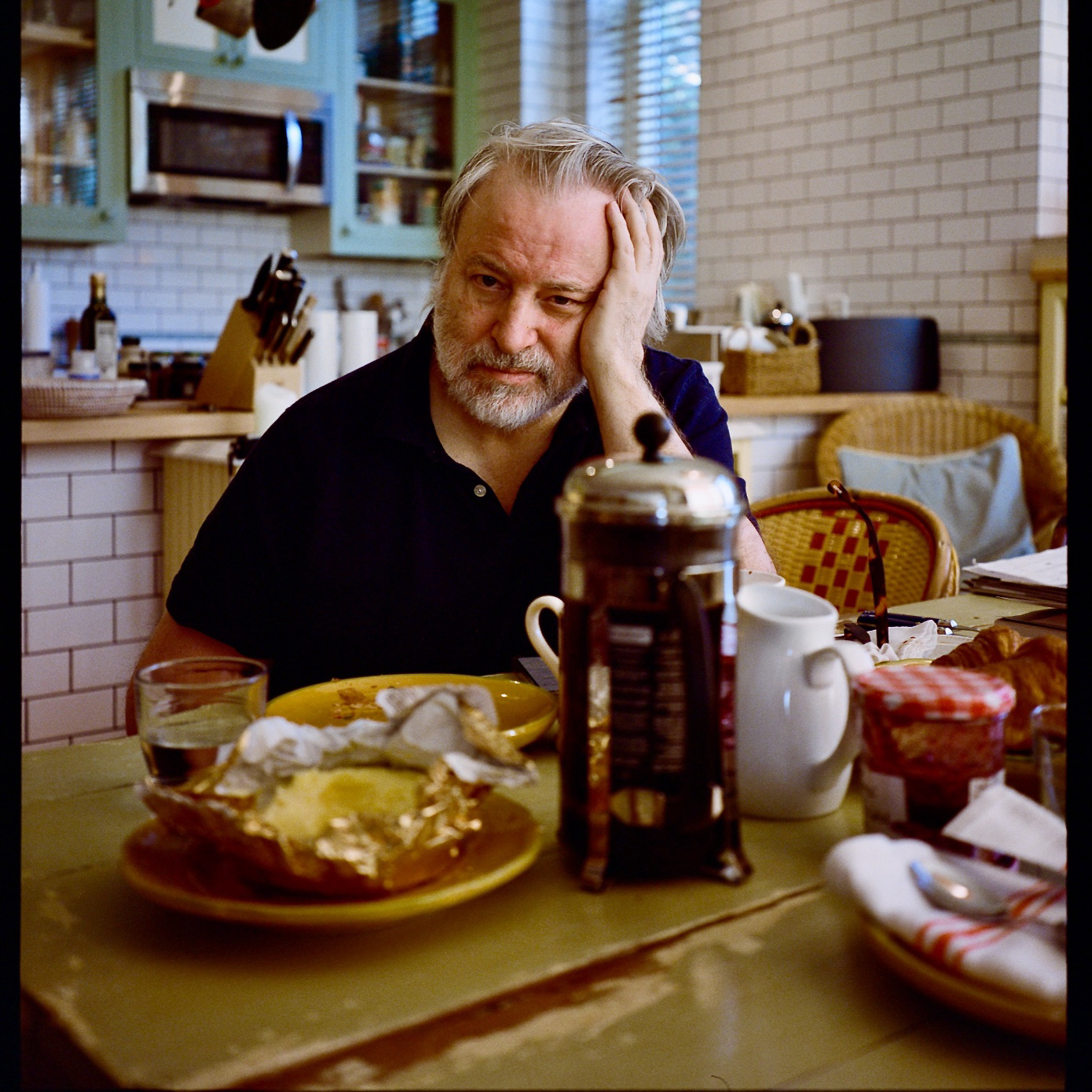

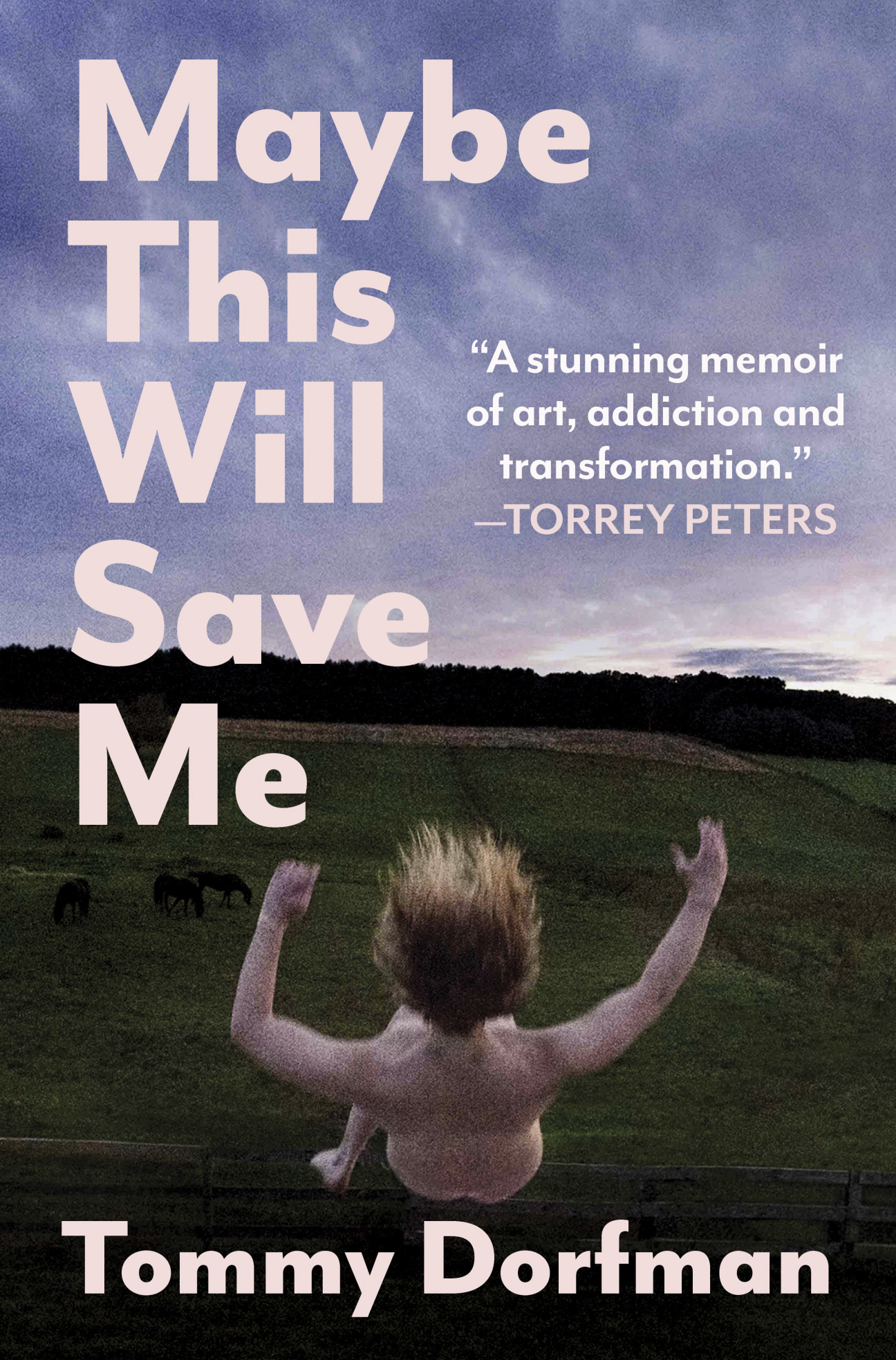

Dorfman’s memoir of addiction, recovery, coming out and coming of age, Maybe This Will Save Me, is out at the end of this month. Last week, I spoke to her about Becoming Eve, boom boom, mysticism, memoirs, skinny jeans, and more.

I thought we could start by talking about what drew you to the role of Chava in Becoming Eve?

It was a really traditional process in that my agent sent me the script, and I read it.

And that's beautiful, because this play is both deeply traditional and deeply committed to subverting tradition...

[Laughs] I was really drawn to an exploration of Jewish identity in a contemporary play that deals with autonomy and love and breaking ancestral traumas. It was unlike anything I'd ever read, and I really attribute that to Emil’s poetry. I was also excited about puppetry as a device because I'd never done anything like that before. So it felt like there were a lot of ways that I could grow by doing this play, both as an artist and as a person.

Emil has said that, beyond his love of puppetry as an art form, he made the creative choice to include them because they serve a purpose metaphorically—they demonstrate that we contain multitudes by showing multiple people working together to move one body. What was working with puppets in this play like for you?

I was certainly trepidatious about the endeavor, but ultimately really excited about how it would challenge my work as an actor to use a different body, operated by multiple bodies, and channel character. One of the more beautiful gifts I've gotten from working with these puppets and the amazing artists who build and operate them is the gift of focus. I get to completely transcend where I am on stage and go into these former versions of Chava, which mirror parts of my own experience and the dissonance I felt with my own body at those ages. It’s been really healing to do it through puppetry because I have some space and safety in that exploration. For me, memory does operate as lore, as a perceived idea of how something transpired. I find my memories—and I worked through a lot when I was writing my memoir—are weirdly cinematic.

The idea of “memory as lore” calls to mind the lore that this play hinges on––this clever re-reading of a Biblical story. That reading, and the play, feel predicated on a Jewish conviction that there are infinite interpretations of any given tale. A memoirist might have a similar orientation towards the world, aware that they are telling one of many possible versions of a story. What was it like acting in this play after writing your memoir?

It was quite affirming in that there isn't space, nor should there be, to unpack every single facet of my life. There were so many parts of my lived experience that were not valuable for the book. The same felt true for this play, which was a beautiful reminder that narrative requires editing. Working on this, having read Abby’s book, knowing Abby, and seeing what memories were of value for this story to be effective was a reminder that we should feel free to edit our lives in useful ways.

Your memoir plays with temporality. You begin each chapter with a tarot card reading as a temporal framing device and render a form of trans time that I hadn't seen on the page before. Can you talk about how you approach timelines?

I wanted to maintain integrity in how I think about my life, which isn't linear—but I also wanted to make sure that when it was all put together, if you know nothing about me, about trans people, about addiction or recovery, it would still feel like there was a beginning, middle, and an end. So my approach does feel inherently like a trans structure, one that is coming into the world in a new way. The way we think about time is distinctly different from cis people. I never felt like I was in the right time until I started to realize my womanhood and share that honestly with my community. I always felt like there was an incredible amount of distance and confusion between where my body was in space and where my soul or head was. So, the reason tarot made sense to me was because memory can hide itself, and I needed a way to access parts of my life that had remained uncovered for a long time.

The Kabbalistic readings in this play come from a mystical tradition, like tarot. Did working on this play change your relationship to your Judaism?

I didn't grow up in a religious household, and I didn’t even hear the word mysticism until adulthood. It felt really gratifying to work on a play that affirms things I discovered in my twenties and thirties that helped me connect with a power greater than myself. Doing this play felt like being held by my Jewish ancestry in a way I hadn't experienced.

There is a rigorous empathy in the depiction of Chava’s journey and her family’s complicated, tenuous ability to understand her. What was it like to work on a play operating on so many different levels of intellect and compassion when the larger discourse is often lacking both?

As we watch the world shed many layers of skin right now, to put it generously, the play is a reminder that there is no one way to live. You can, like a kaleidoscope, look at an ancient text, a current text, a poem, a conversation, a person through multiple lenses at the same time. The play ends with grace from Chava and her father, in this realization that as hard as we've been fighting, we're not going to come up with a solution that's mutually agreed upon. Instead, we're going to go our separate ways, respecting each other's perspective. It's a lesson for all of us right now in a world that's so violent and combative that if we could take a second to pause, reframe, and perhaps find more acceptance within our resistance, we could be more successful in growing in our lives.

Both the play and your memoir illustrate a certain agility of perspective—basically, being bitingly witty in one sentence while also willing to admit you're crying in the next. Can you talk about bringing humor into such wrenching stories?

The only way I've ever gotten through life, especially the terrible things, is through finding some humor in them and realizing that even in the most abhorrent places I've gone, in the depths of my personal hell, there is still a bit of wit, a bit of humor I can use to survive. I also think people need that break, you know? You could buckle up and take the flatline trauma ride, but I don't think anyone's going to leave that experience having learned all that much, because you need time to digest your traumas. Humor is a palate cleanser, so you can go back into the next terrible moment.

It's a combination palate cleanser and metaphorical metabolism-boosting supplement for trauma digestion.

Exactly—it's pickled ginger between sushi rolls.

I wanted to ask you about costuming. Your character pivots between two main looks: a very feminine sundress and a more boyish jeans-and-hoodie combo. How did those fits fit, if you will, into your understanding of the role?

It's a really clear picture we're painting with Chava of how we present ourselves with people we feel safe around, or when we're trying to affirm our gender in public, versus how we present ourselves in circumstances in which we feel less safe. Chava knew she had to put on boy drag to have the conversation with her dad. That feels important and relatable. The first time I traveled internationally, when I was further along in my transition but before the gender marker on my passport had changed to female, I went back somewhat to a boy version of myself in my presentation. Then, the first time I traveled with “female” on my passport, I dressed more feminine than I would ever dress at the airport, because I was nervous about going through customs and having them question my gender.

On the topic of fashion and gender presentation, do you have any thoughts on “boom boom,” the ’80s masc-coded power suiting, pro-greed trend happening right now?

The conservatism trend in dressing is not surprising to me, but I still think there's a lot of people who are dressing in that bimbofication of femininity mode that feels really affirming and sexy and fun as well. I have two wolves inside of me: One of them is The Row, and one of them is Juicy Couture. I'm kind of interested in challenging the world through dressing a bit more this summer.

That feels really aligned with the way this play challenges people to remember that there are innumerable interpretations of any story, but especially the most archetypal ones.

There's a way to approach that sartorially that offers me the freedom to play different characters. I just found three vintage Versace suits from the late ’80s, early ’90s. If you're going to play with fashion, you should be looking at vintage buys because it's untenable to rely on an industry that has been running itself into the ground. But constraints like recessions offer us new ways to explore how we consume. More often than not these days, I'm in a process of editing in my life.

Can you name something you think is overrated, underrated, and accurately rated?

Underrated: Addison Rae, although that's changing. Accurately rated: skinny jeans. Because it's okay to have divisive opinions about them. I think we can all agree that Katy Perry's been overrated for a long time, and she's only proving that more and more every day. But ultimately, I'm like, let a girl live! I think there's a deep conservatism happening in entertainment. I don't know if overrated is the right term [for it], but I know every time I see Gwen Stefani doing a prayer app ad, I'm feeling a little stressed.

What is your favorite place in the city to people watch?

The subway.

Any particular train?

Honestly, the line that I'm always most shocked by is the 6. It's confounding. I don't know who is taking the 6. It goes through Murray Hill and the Financial District. I have questions about that. But then it also is one of the more efficient trains. So any subway line, but particularly ones that aren't your normal line, because you realize how small life can be in New York if you want it to be.

What about your favorite spot for flirting?

I will flirt anywhere. I love flirting at Dimes Deli. I love flirting at house parties. I am an inherently flirty person, and I've always been most successful on these streets and not on the apps. New York allows for that.

What is your favorite place to cry? Many people also say the train for this one.

I hate crying on the train.

I personally prefer to cry in my house, but sometimes it has to happen outside.

I love crying in an Uber or a taxi, looking out the window. However, I was just doing this the other day, and my Uber driver pulled over to ask me if I was okay. I was like, Thanks for checking. Let's keep going. I had my sunglasses on, and I enjoyed the humor of it. Honestly, it kind of broke me out of my crying spell.