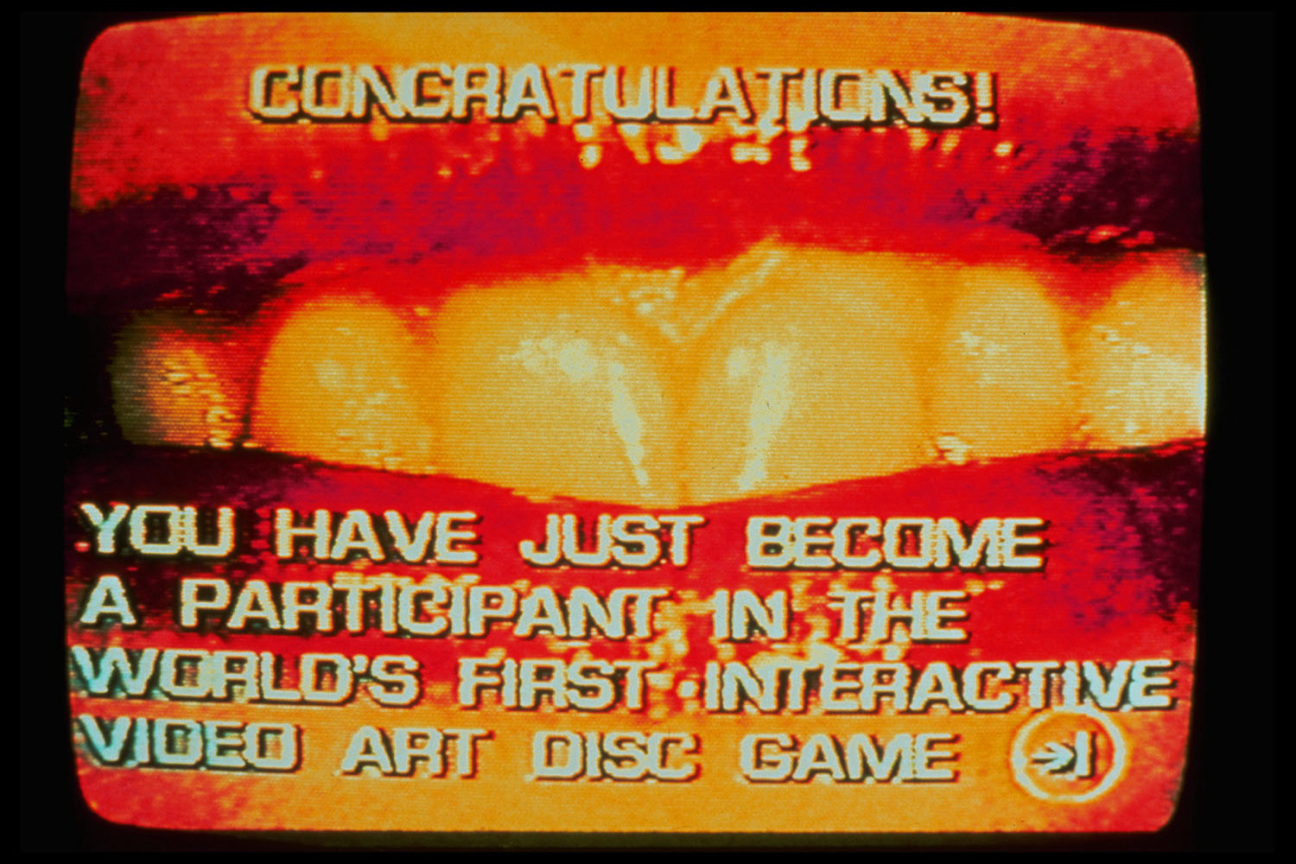

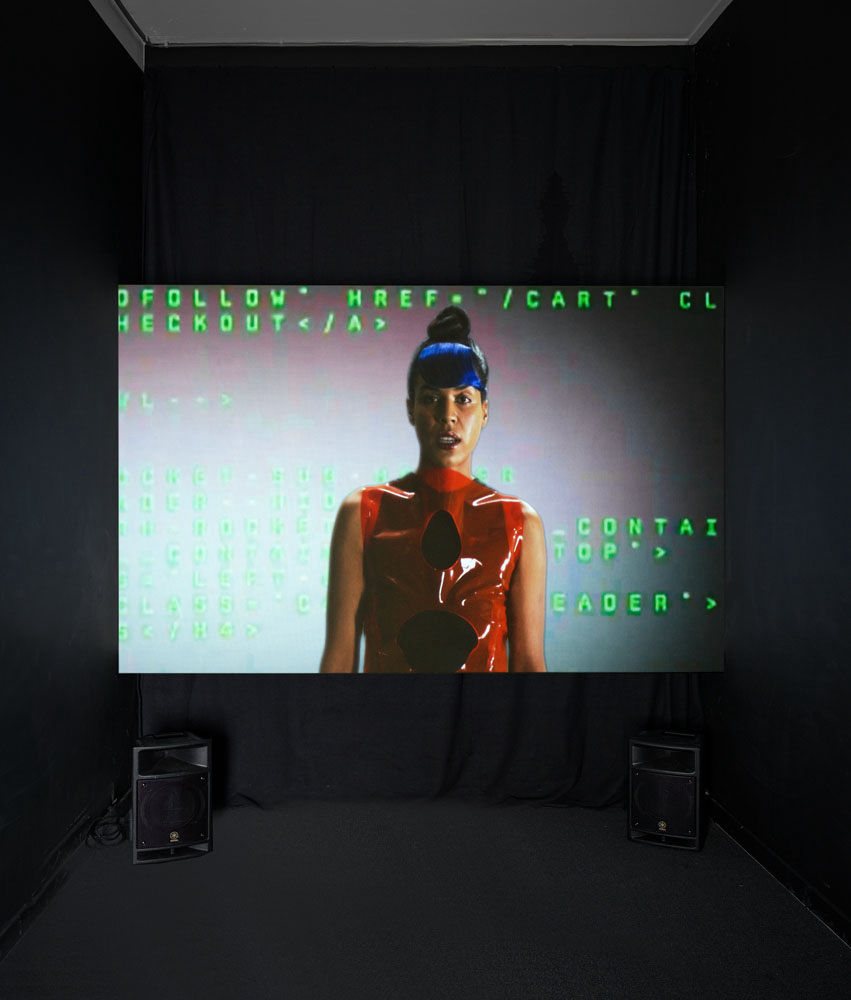

For much of Lynn Hershman Leeson’s nearly six-decade-long career, her prolific contributions to the ever-evolving landscape of New Media—from her use of then-radical technologies like touch screens to her Tilda Swinton–starring cyborg comedy Teknolust—were treated as an asterisk. Thankfully, that oversight has begun to be corrected in the past decade, through a slew of exhibitions and catalogs. At 82, Hershman Leeson is busy making art about another kind of future: immortality.

CULTURED: What are you working on these days?

Lynn Hershman Leeson: I made three films last year, two about gun violence. One is an installation, and another one is cyborg; ChatGPT wrote and performs it. I've been [working] nonstop, but mostly what I'm doing now are projects about immortality and scarcity. I actually had some anti-aging capsules made in China. I couldn't do it in the United States or Europe because they don't allow that, especially for humans. They're doing it on rats but not humans.

CULTURED: What did that process look like?

Leeson: Well, as usual, I have to work with scientists who have more legitimacy than I do. They're the ones that contact the labs, who will do it because they’re real scientists wanting it rather than an artist. I exhibit them with syringes in a refrigerator because they have to be kept at 30 degrees. The refrigerator is covered, the front of it is a mirror except for a little opening where you can see the syringes.

CULTURED: It's reminding me of your work Room of One’s Own, 1993, where you look through a peephole.

Leeson: A lot of my works are about surveillance.

CULTURED: What is drawing you towards immortality these days?

Leeson: My age, I think.

CULTURED: Looking back, what was your first experience with art?

Leeson: From the time I was two or three, all I did was draw and go to museums. I went to the Cleveland Museum of Art almost everyday. It kept me sane. I have really deep feeling for that museum and for the artists that are in there, many of whom I copied in order to learn how to draw.

CULTURED: Was there a particular room or piece that you remember going back to?

Leeson: Yeah, I remember the Rembrandts and the Leonardos. They also had a big Chinese collection that I would visit. I think I learned to draw from the Leonardo da Vinci drawings that were in there.

CULTURED: Tell me about your impulse to draw and go to the museum almost every day. What did it afford you as a young child?

Leeson: Sanity. Being able to do something and see the result seemed so magical. To take a pencil or a pen and create this trail on paper. It was always an adventure.

CULTURED: When did you start thinking that art could become what you did?

Leeson: I never thought it would be what I did. I started trying to get my work in galleries when I was probably close to 40. There were a couple in San Francisco that showed my work, but it wasn't until I found places outside of San Francisco, particularly in Europe, that I started thinking more seriously about the potential. At that time, nobody was showing women, and nobody was buying women. Over time, it became more possible, but certainly not in the Bay Area. You had to find venues that would appreciate your work and treat you fairly.

CULTURED: Do you remember any of those initial moments where you felt like someone was seeing what you wanted to be seen in your work? Someone who knew your work was worth exhibiting, and needed to be seen?

Leeson: In 2013, I told the artist and curator Peter Weibel, who was [then] the head of the ZKM Karlsruhe museum, that I had never exhibited the breadth of my work. He scheduled a retrospective and showed most of it for the very first time, and people realized that I was doing so many things before anybody else, like that I had done the first media works, which even I didn’t realize.

CULTURED: What kept you going for those 54 years that the art world wasn’t paying attention?

Leeson: I didn’t really think I could ever show my work, or make a living off of it, but it was just so thrilling for me to invent things and take chances and see the result. It was the process of making things that was so exciting.

CULTURED: What was it like when people started paying attention?

Leeson: It was pretty unbelievable. The reviews were so positive. It was discovered that a lot of the work I had done predated the people who were making the work that I invented. It was life changing. Pamela Lee wrote about my breathing machine. She said, “Why didn't anybody ever write about these?” I said, “Nobody would show them.” She was the first one that wrote about it.

CULTURED: Is there a project that you made in the past that is something you now think about differently? Something that’s been resurfacing?

Leeson: If anything, it would be the "Roberta Breitmore" project, which was almost a decade of creating that character and living as that character and collecting all the artifacts that proved that she was real. That really set the idea of the conflict between what was real, what wasn't, and how you prove it.

CULTURED: What do you think people need to prove that they’re artists?

Leeson: They have to do it. The whole key is just believing in what you're doing and continuing to question what you're doing and creating things that you feel are vital to your time. I couldn’t just use painting and drawing because I can’t compete with four centuries of that work. Living in the Bay Area, I used the materials of my time, particularly technology, to talk about the issues of my time.

CULTURED: Do you think that you've given up anything to be an artist?

Leeson: Money, because I had to pay for everything myself and still do. I don't have a big bank account but you know, that's okay.

CULTURED: What advice would you give to a young artist who looks up to you?

Leeson: To keep your sense of humor and not to throw anything away.

CULTURED: What is the best thing about being an artist?

Leeson: What could be better? You get to do what you want a lot of the time. It’s constantly inventing possibilities of how to tell stories and present situations, with very few restrictions.

This interview is part of a series of conversations with female artists over the age of 75. To read more, take a look at our stories with the avant-garde Pippa Garner, Brazilian sculptor Sonia Gomes, and prolific creative Liliana Porter.

in your life?

in your life?