It didn't take the collective intelligence of Twitter long to realize that the chaos of our decade is embodied by two drugs meant for horses: ketamine and ivermectin. The former, a horse tranquilizer, has been a party drug for generations, but is newly and heavily marketed as a treatment for depression, addiction, and general soullessness. The latter, a livestock dewormer, ascended the manure pile of right-wing conspiracy theories as a dubious (and thoroughly de-bunked) prophylactic for Covid-19.

Maybe we’re not so far from the days when railroad baron Leland Stanford set out to engineer the optimal racehorse on his Palo Alto ranch. The horse, after all, is a powerful symbol—a laborer turned ornament, an acceptable outlet for the fetish of good breeding. The New York police force still maintains mounted units at great taxpayer cost, and on social media, the “horse girl,” a human in thrall to animal strength, is resurgent. The horse promises to transport us to a simpler, nobler time. Meanwhile, your modern-day robber baron (read: Stanford Man) dresses like a slob and peddles snake oil online.

In eras of existential stress, societies turn to superstition. On one end, the mental health establishment’s embrace of psychedelics promises to revive the holistic revolution of the 1960s. On the other, splintered factions put their faith in “Q,” who preaches the gospel of “doing your own research.”

As in previous periods of tumult, artists play their role as soothsayers and deconstructionists, holding a mirror to the absurdities and contradictions of the moment. Paige K. Bradley, a writer and artist, provides cryptic fields of signs, inviting us to connect the dots with little pieces of red yarn. The sculptor Harris Rosenblum produces equally eclectic work that puts various belief systems in dialogue. New York artists Rachel Rossin and Brian Oakes have returned to ancient Christian symbolism through the essentially mystic alleyways of technology.

These four artists depict what could be described as the defining urge of our era, reaching for a form of devotion through their own constellations of belief-anchoring objects. Through Bible stories, video games, or a medicine cabinet of horse pills, artists are palpably seeking. In this endeavor, they share a dream with both the dissociating millennials snorting K and the amateur eschatologists hoarding equine antiparasitics.

This October, Bradley published Drive It All Over Me, a long, spiraling essay in response to “Bad Driver,” a 2021 show by the artist duo Jay Chung & Q Takeki Maeda at Maxwell Graham in New York. In one passage, she describes a pantomime horse as “two people in one outfit,” a pair of fractured beings loping along awkwardly, trying to reinhabit some truer form of mammal. Jay & Q’s retrospective at Redcat nine years earlier centered on their sponsorship of a middling show-jumping prize in Germany. In it, two video works positioned the poetic litany of the horses’ names against a ledger of the pair’s conceptual artist forebears, like Christopher Williams and Marcel Duchamp.

Bradley does what she was tasked with, then takes things a step farther, invoking conceptual artist Jack Goldstein and his impenetrable late artist books—typewritten binders of quotes arranged like concrete poems. Goldstein—who once spent a night buried underground as a performance piece, and did heroin alone in his trailer until he suicided—is a saint in the sub-rosa canon of paranoid art.

His biographer, Richard Hertz, coined the phrase “CalArts Mafia” to describe the artist’s cohort. Bradley and I are both CalArts alumni. Goldstein and I share a birthday. These are the sorts of discursive connections prized by conspiracy theorists and artists—the type of thinking that makes ivermectin seem like a good idea.

Where ivermectin connects the dots, ketamine buffers and transcends. The insights it offers, at ascending doses, can be dissociative, epiphanic, or hellish—but nobody takes it too seriously. We used to talk about irony. Now, the culture’s response to worldwide anxiety is ambivalence. God is a mushroom and an A.I. The worst will happen, and it won’t.

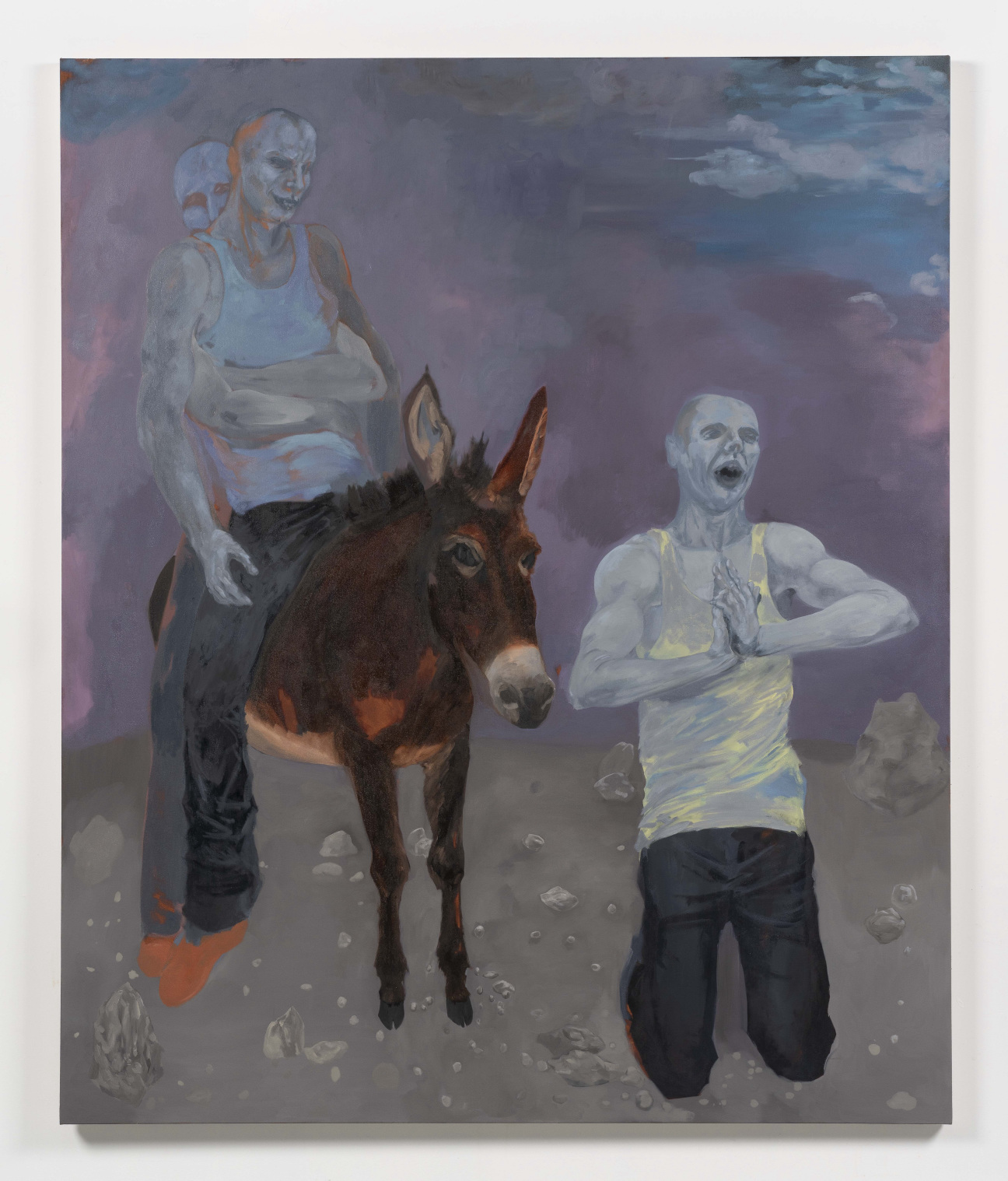

The puckish Catholic symbolism unfolding among certain echelons of the godless art landscape, particularly along a stretch of Chinatown in New York, has a similar tenor. At Reena Spaulings, a painting show by Georgia Gardner Gray called “HeBombs” casts stand-up comics in various saintly and Christ-like poses.

Harris Rosenblum’s show at Sara’s mixed the mythology of the tabletop roleplay game Warhammer with Bible stories, prepper gear, and decidedly profane materials: a lamb made from a combination of soy-based resin and bone broth, pink Realtree reliquaries, and a statuette of Hatsune Miku (the synthetic Japanese pop megastar who appears in concert as a hologram) made of clay sourced from a Wendy’s construction site. The artist works in the niche between nerdiness and saintliness, depicting the struggle for belief itself—a squirm-provoking inquiry in today’s ideological climate. Gamers may seem maladapted to outsiders, but the same was said of early Christians.

Technology seems to offer new routes to divinity, prompting artists working with electronics to hearken back to careworn idioms and old gods. In Rossin’s recent show at Magenta Plains, an installation was shaped and lit like a chapel, and chunky pale paintings delicately printed with images of mechs—giant battle robots—lined the walls like altar panels. A round disc of LEDs on the ceiling played heavenly heat-map imagery and digital renderings of angelic, disembodied nerves.

Cyborgs embody the desire to reengineer ourselves as wholly synthetic beings: unfeeling, unanxious. A recent group show at Blade Study, titled “Epiphany,” and an early show at Dunkunsthalle, a project space Rossin runs, featured sculptures by Oakes: circuit board angels, their sharp black wings studded with LEDs, hanging in space from their wires. We are far from Precious Moments, lost in the awesome swirls of eyes and wings that characterize heavenly messengers in the Old Testament.

Be not afraid, angels like to say. Anxiety is the unmanaged fear about what you can’t know or change, dwelling on a feeling of impending doom. Call it the Singularity, or the apocalypse, or just Sunday morning. Even a glimpse of that final pale horse would bring relief.

in your life?

in your life?