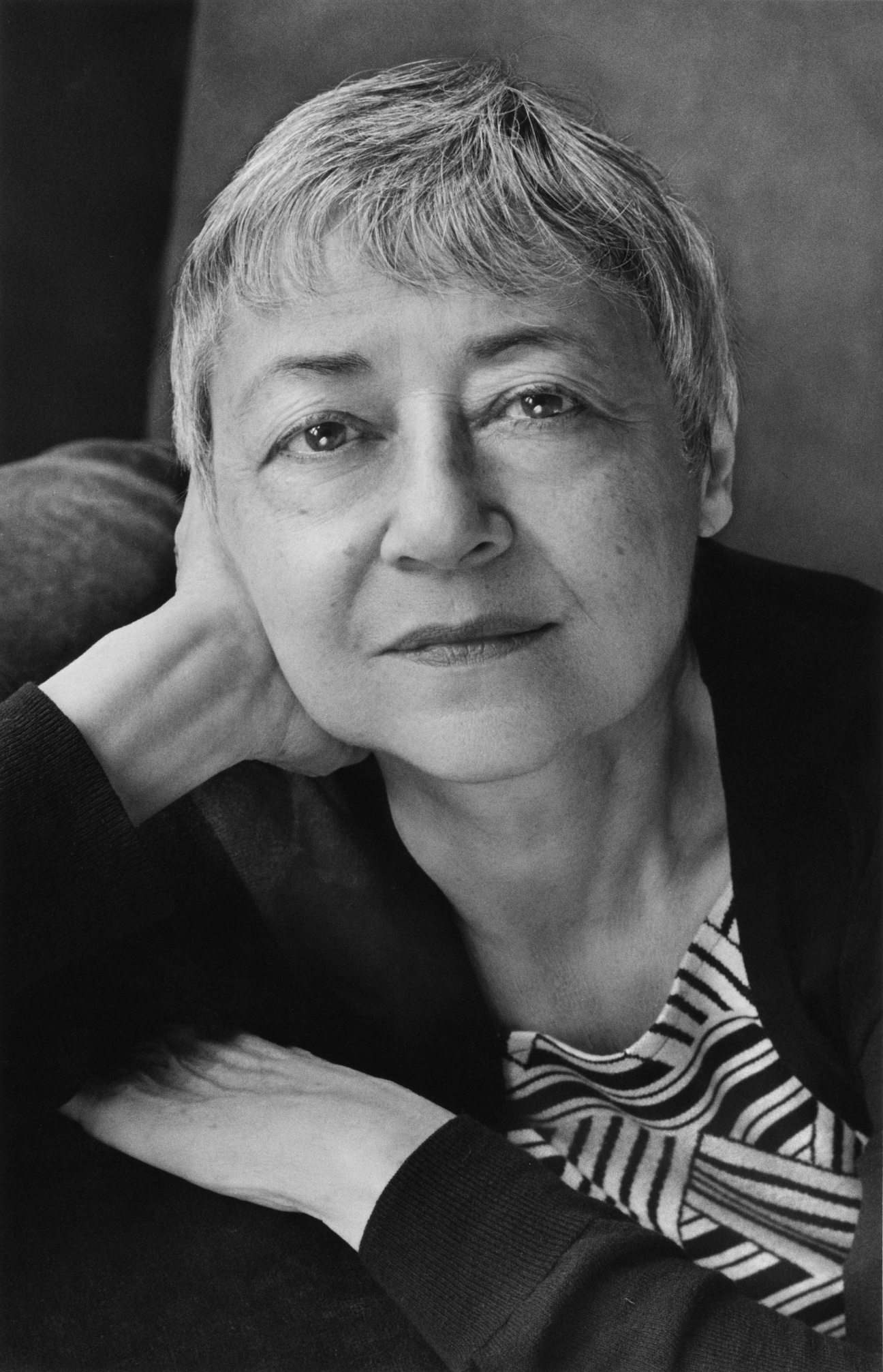

Sigrid Nunez is upstate, escaping the Manhattan bustle of her daily life for the serenity of the Yaddo writers’ retreat in Saratoga Springs. Her latest book hasn’t even hit shelves yet, but the author is already ideating, ready to dive back in.

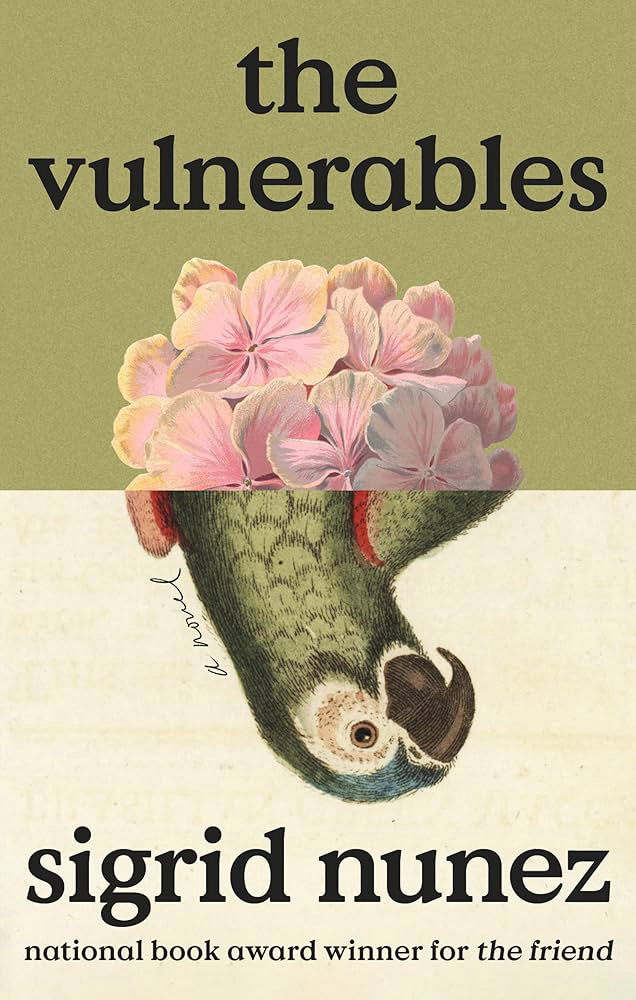

The Vulnerables, her ninth novel, is a winding chronicle of life during the pandemic. An unnamed New York protagonist finds herself bird-sitting a macaw while cohabitating with a chaotic college student who appears at the door without warning.

At Yaddo, Nunez is sharing space herself—with a “terrifically friendly” dog who keeps her company while she sets to work unspooling the narrative of her next book. To mark the release of The Vulnerables, she takes a moment to reflect on the novel and her renegade approach to literary norms.

Sophie Lee: The book opens with a passage about the weather, and notes that this is not the proper way to begin a book. Did you take that as a personal challenge?

Sigrid Nunez: I started writing this book in the spring of 2020 when we were all in lockdown. It really just came to me. The first sentence of Virginia Woolf’s novel The Years is, “It was an uncertain spring.” I thought, This is an uncertain spring. Dickens’s novel Bleak House also starts with the weather. I grew up being told that “It was a dark and stormy night” was the stupidest, worst, most horrible way to begin a book. But when you think about it—why?

Lee: Your narrator is a writer living in New York. It’s hard not to think that her character might be inspired by your own life.

Nunez: It’s unavoidable. If you have a first-person narrator to whom you have given your gender, your age, and your profession, it would be silly to expect that readers wouldn’t think that some of this was coming from the writer’s own life. But the truth is, I don’t write autofiction. I write books that are really hybrids.

There’s always a narrator that I, as the author, identify with strongly. If I’m having this narrator reflect on certain things—what it feels like to be in lockdown or what it feels like to be alone, what she thinks of a certain movie she’s seen—that’s going to reflect Sigrid’s feelings and ideas. But the things that happen in my books are almost exclusively invented.

Lee: I remember this line from the book, about choosing a pseudonym: “Sugared Nouns was the computer’s suggestion, after spell-checking my name.”

Nunez: That was real. I just couldn’t resist! I’ve always wanted to use it somewhere; it was so funny. I thought, Well, now you’re naming the narrator your name. That is usually only done in autofiction, but where else am I going to put that hilarious thing?

Lee: You started as an editorial assistant at the New York Review of Books.

Nunez: I wish I had paid a little bit more attention. I didn’t really want to be there. Our jobs as editorial assistants were 100 percent clerical. We had typewriters and phones on our desks. We kept saying, “Why don’t they hire real secretaries?” They would’ve done a much better job, because our typing skills were not so good. When the editor would dictate, it was like a panic attack.

Nevertheless, you could watch the editing process, you could see how everything was put together, you could read the writers, and I did that. But I was always distracted by the life of the young and cutting corners, keeping the job as minimal as possible. It is a moment in time where you have a certain invisibility, which can be an advantage as far as being a fly on the wall.

Lee: You weren’t turned off by the literary world after they made you get their coffee and do their typing?

Nunez: Not at all. There were so many good writers connected to the Review and, because it was New York, they were often in the office. You didn’t have a privileged position at all, but you had the privilege of seeing these people you admired. You didn’t think, Why are they not noticing me? Why would they notice you? You’re an idiot. You can’t even type.

Lee: When did you realize you could make a career out of writing?

Nunez: I went to an MFA program. I worked at the Review a little before and a little afterwards. It was a hard path, but it was an obvious path. That’s what I had to do: Sit down, keep writing, try to get something good, and try to get it pub- lished. I always wanted to do that even when it wasn’t working out, even when I didn’t like what I wrote. I just plowed on.

Lee: Did winning the National Book Award for The Friend in 2018 feel like a turning point?

Nunez: It didn’t, because I’d written so many books before. It changed one thing hugely: Because of that prize I now have a large number of foreign translations.

Lee: Are future readers, say 30 years from now, a consideration for The Vulnerables?

Nunez: I never think about what the book is going to be, how it’s going to be read years from now, or whether it will make sense. I’m only concerned with now. There’s another rule of writing: Never tell the reader something she can figure out for herself. Never assume that your reader is not as intelligent as you are.

You don’t have to explain everything; this is boring and repetitious. I’m talking to someone who is not only as intelligent as I am, my equal in all ways, but also somebody who’s just been through what I’ve been through. When you read a book about the present day written as if it were a historical novel, you just want to throw the book across the room.

Lee: There’s obviously an intergenerational narrative here. Were you thinking about that a lot during the pandemic

Nunez: You mean, did I fantasize about some gorgeous young hunk who was suddenly in my space? Who was also a really nice guy who just wanted to get high together? You know, maybe I did!

in your life?

in your life?