“I needed more space, more breathing room and more silence,” says artist Mimi Jung of her somewhat recent move from bustling Los Angeles to Helena, Montana. Having grown up in Seoul and New York and based her practice in LA for the last nine years, Jung notes that while the urban environment has a huge impact on the color scale of her large fiber works, she had always dreamed of “being removed” from it. Last year, “I had started feeling drained by the demands of the city,” she explains and after a pandemic-shortened stint as a Kohler Arts/Industry resident in Sheboygan, Wisconsin in March 2021, she and her husband packed up their LA car and headed for the stunning landscapes of Montana.

Now, slightly more than a year since, she has settled into her new home and studio in a place so inspiring the “work is flowing out of me,” she says, but also so racially homogenous that diversity is more of an abstract than a reality. According to 2021 United States Census data, Helena is approximately 93 percent white, five percent Latino, one percent Native American, less than one percent Black and less than one percent Asian. The first question she receives about Montana from fellow artists of color also longing for more space and an immersion in nature is “What’s it like?” Jung shares. It’s a question that has a subliminal message: “Do you feel safe there?”

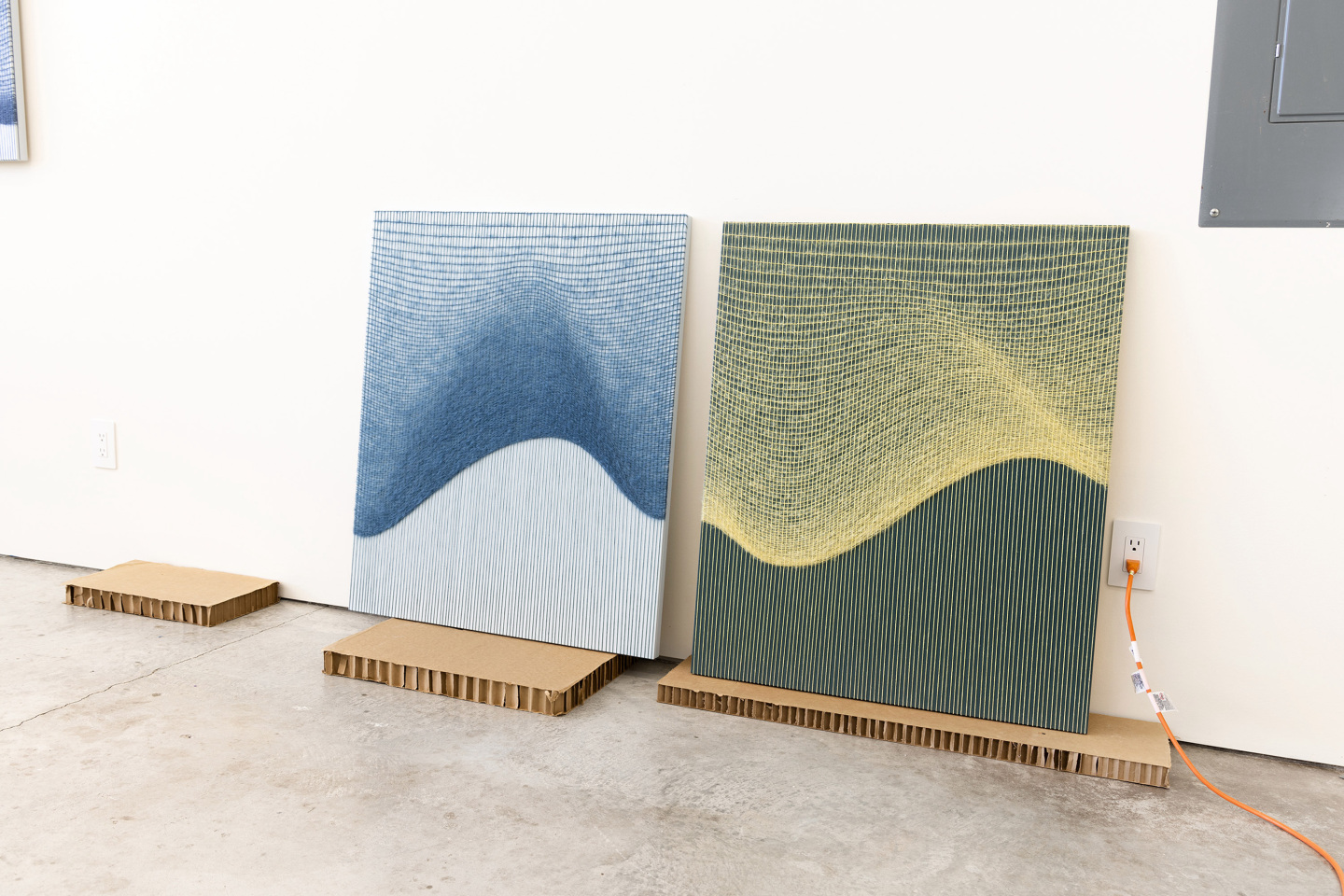

An answer might be found in Jung’s latest body of work currently on view in “Shields,” her first solo show at Helen J. Gallery in Los Angeles. These vibrant and illusionary pieces play on weaving’s two most basic elements—warp and weft—to create on-painted canvas visions of three-dimensional textiles much deeper than they truly are. For Jung, they are a response to an “overwhelming emotion” that was triggered within her after the Atlanta spa shootings on March 16, 2021, in which eight people, six of whom were Asian women, were murdered at three spas in the city.

Experiencing the news of this massacre alone in a city with no community of neighbors who can truly relate brought Jung back to her first memories in America: stepping off a plane from Korea at John F Kennedy Airport in New York at 8 years old—the first time she experienced diversity and the first time she experienced racism. Later, “being part of an Asian American community in New York and Los Angeles, I felt I had a layer of protection from racism,” she says. Though most Montanans’ wariness of outsiders comes from fear of a changed way of life, that layer was shed for Jung when she moved to the Mountain state.

After the Atlanta shootings, police Captain Jay Baker told a press conference that the killer had just had a “very bad day.” It led Jung to wonder: who deserves protection?—and to begin to explore that query in yarn, one thread at a time.

“The core component of my work has always been identity and self-preservation,” says the artist who has previously been hesitant to share her inspirations too deeply for fear of pigeonholing. “It’s about how our narratives are constantly evolving to fit into a much larger cultural narrative in order to survive,” she explains, describing the kind of code switching that is a necessary reality for many people of color. As a viewer, one negotiates their position with these works, trying to peer through its woven veil to see where the flat surface beneath ends.

To show this highly personal series, it was important that Jung collaborate with a gallerist who she could trust with sensitive content. “As a person and an artist, I have been spoken to in ways that are so soul-crushing,” she says, noting that most artists of color can share stories similar to hers in the nation’s most diverse cities: comments on how to pronounce her name “better;” placing en vogue narratives onto her work; or simplification of the art’s concepts to a single sentence on identity. “I’m a Korean artist and being limited to that was scary,” she says, but in Helen J Park’s gallery, she found kindred spirit and understanding.

“A collaborating gallery is like dating,” says Jung. “This work had to go there at this moment.” Heading back to Los Angeles for installation and the opening may feel like a short homecoming of sorts, but Montana is where she plans to set roots. “There is a lot of new happening,” she says of what certainly feels like a pivotal moment in her practice, “but there is a lot of intention behind it.”

in your life?

in your life?