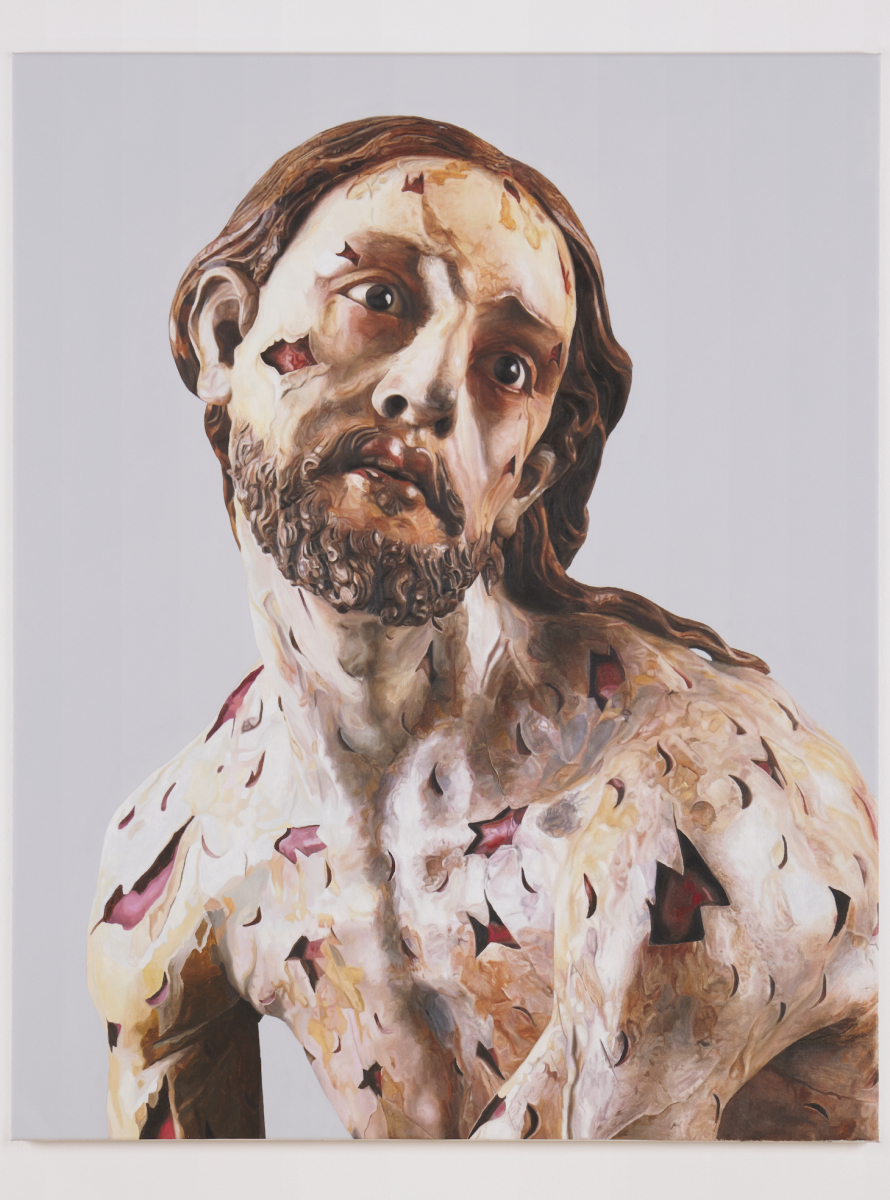

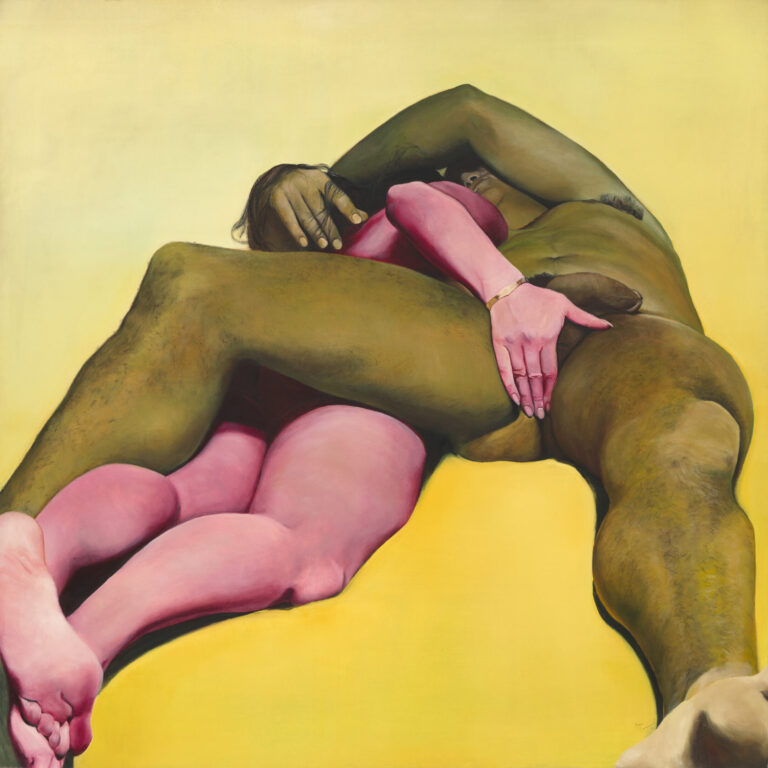

At 30, the painter Hamishi Farah, an artist of Somali heritage, raised in Australia, and currently living and working in New York City, has quietly but steadily produced an impressive and incisive body of work where elusively fermented portraits of coquettish toucans, dewy eyed, bee-stung lapdogs, insects and arachnids commingle with images culled freely from art history and pop culture; there is, for example, a delicate but expressive portrait of Sasha Obama, another of rapper Juelz Santana and one of Paul Karason (“Papa Smurf ”), a white man whose skin turned blue from a rare form of silver poisoning. The breadth and diversity of Farah’s subjects is a testament to the ambition of his critical project, which investigates “the colonial libido,” aims to “displace the category of the human” and attends to the enduring “impact of Christian imagery on conventions of representation.” He alternately engages these fronts straightforwardly and playfully, headlong and obliquely, all the while developing what functions as an effective annotation on the accepted history of painting.

Perhaps most notoriously, Farah exhibited an intimate painting of Dana Schutz’s young son Arlo, rendered tenderly against a soft, pastoral landscape, in the months immediately after controversy erupted around Schutz’s Open Casket (2016), a painting she made of Emmett Till’s disfigured corpse that was included in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Schutz’s picture, which she argued was a pure expression of the extraordinary and unique empathy of a mother for the death of any child, sparked debates about the fetishization and commodification of Black trauma and experience in the work of white artists and, ultimately, about the larger power and responsibility of images. Farah’s painting too received a good deal of backlash from those who understood it as a hol-low act of retribution, rather than as a prickly visual model through which we can disinter the hidden ways race contorts and controls our ability to exercise basic freedoms. But as Farah’s London gallerist Rózsa Farkas of Arcadia Missa has pointed out, “Drawing equivalence [between the two works means] you have missed a key point… The child in Hamishi’s painting hasn’t been murdered.”

This spring Farah opened two major solo exhibitions, one at his gallery in Los Angeles, Château Shatto, and another at Fri Art, the kunsthalle in Fribourg, Switzerland, that traced the obsessive depiction of Christ’s bodily wounds through our contemporary fixation with images of victimhood and suffering.

in your life?

in your life?