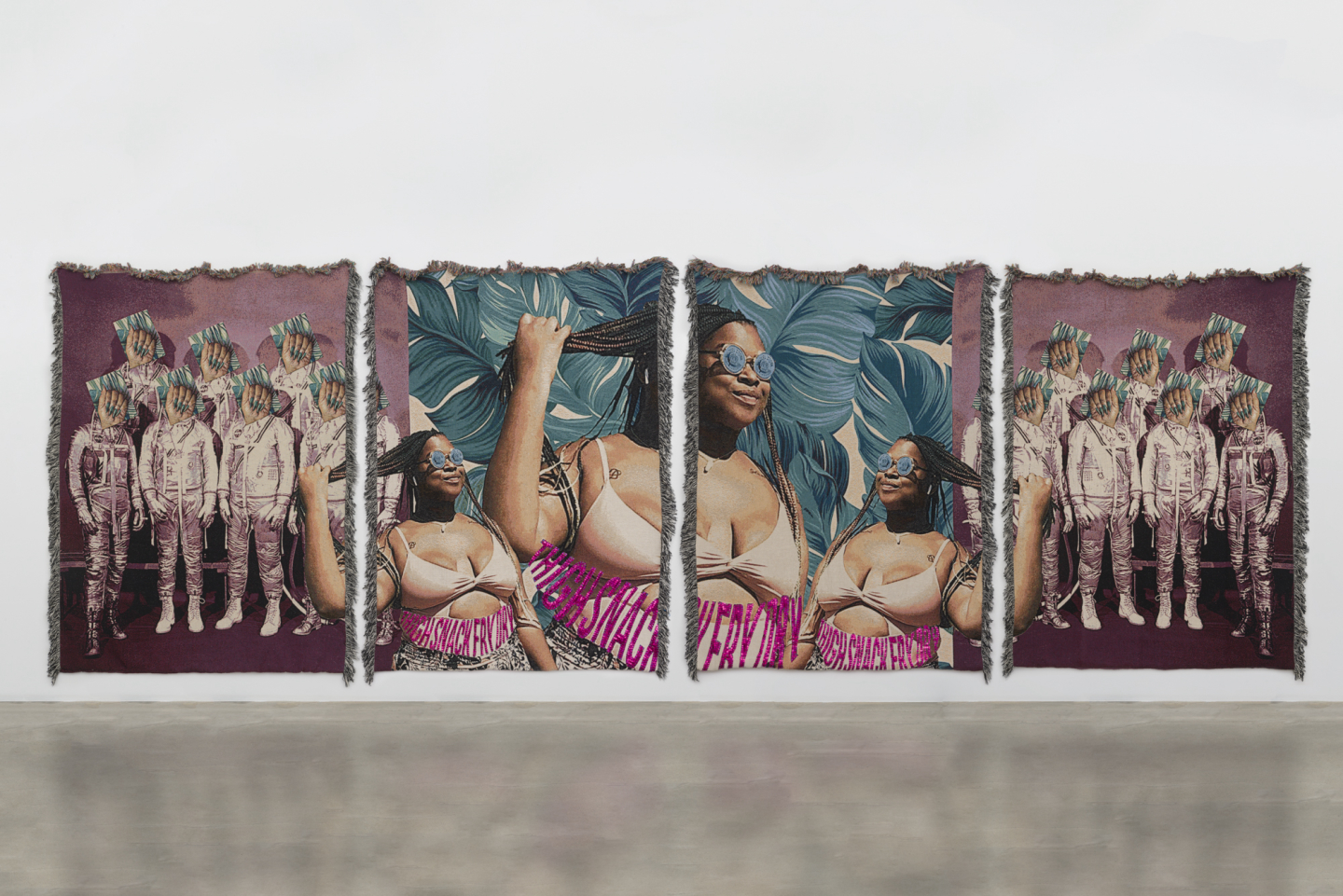

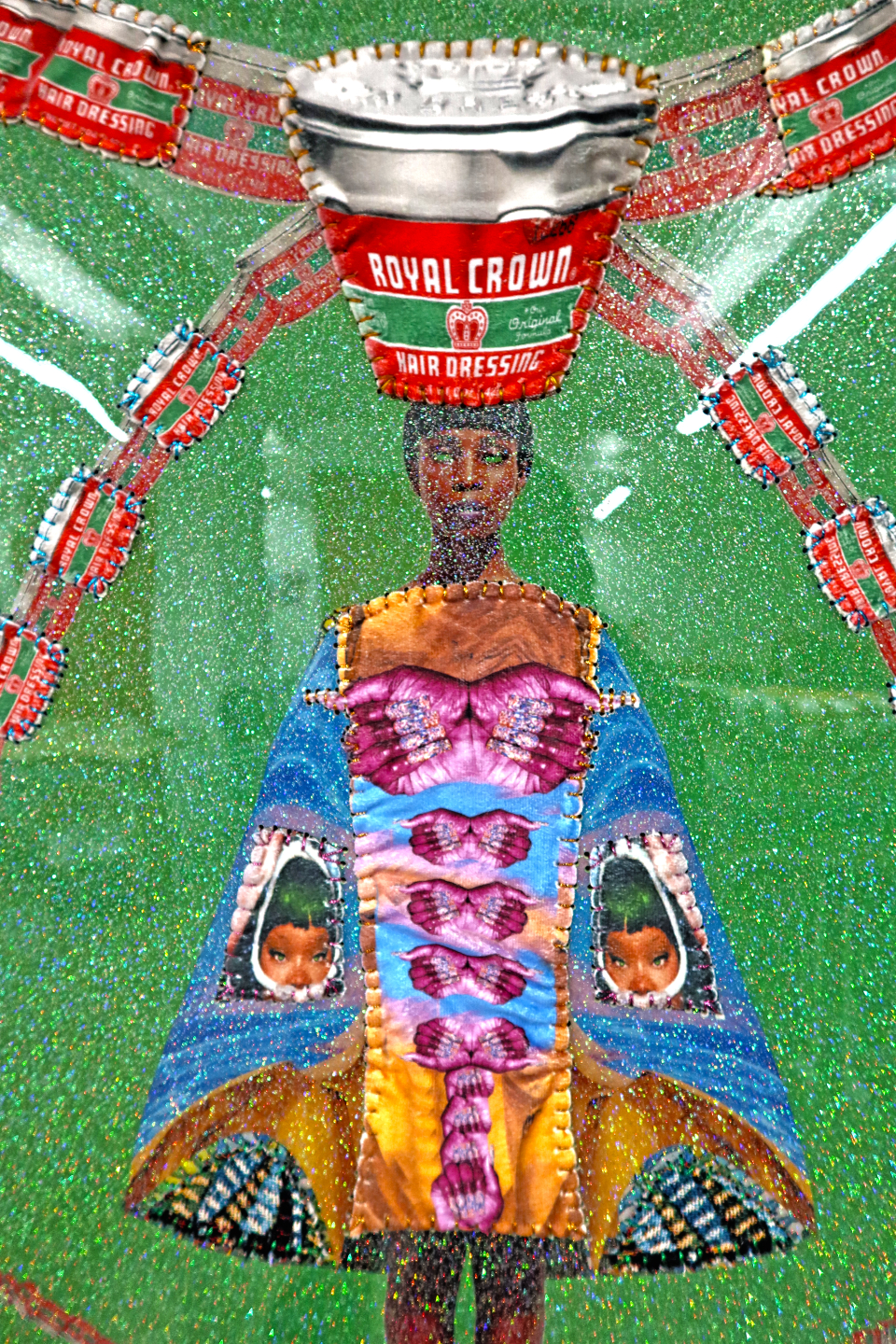

I first encountered April Bey’s work in an exhibition at the California African American Art Museum, where a generous and inventive installation of her richly colored collages made from artificial fur, digitally woven tapestries and figures painted in watercolor and highlighted with glitter introduce Atlantica, a mythological planet the artist establishes herself as an alien emissary for. The aesthetics and construction of Bey’s canvases recall the ecstatic costumes and floats of Junkanoo, a Bahamian street parade that takes place on New Year’s Day and sees the real-world detritus of the prior year given new life as the otherworldly visages of magical avatars. Bey, who grew up in the Bahamas on the island of New Providence, has been dreaming of Atlantica since, as a young girl, she began to ask her father some very basic questions about the world around her. Bey wanted to understand “Why she looked more like her father, who is Black, than her mother, who is white?” Why their hair stood up, and hers didn’t?

Bey’s father was a “science-fiction nerd,” and, sensing that his young daughter didn’t have the vocabulary to understand the nuances of race and colonization, he put their situation in terms he thought she would understand. The two of them were aliens, sent down from another planet to observe and eventually report back on what was happening on Earth. Thus Atlantica was born. The vividness with which we feel this fictive world when in the presence of Bey’s work is a testament not just to the rigor of the artist’s imagination but also to the power of narrative as a force. When she talks about Atlantica, Bey references how the story became a way to cope with a reality too brutal to accept on its own terms, but it also exists as a cipher, through which the often hidden strangeness of existing in a colonial context finds expression. For one, Atlantica was a way to make sense of the violence of the tourist economy much of the Bahamas remains entirely dependent on.

Now Bey lives in Los Angeles. There she keeps a studio downtown and teaches at Glendale Community College, a public institution where Bey says she feels lucky to have the opportunity to have classes primarily composed of BIPOC students from immigrant backgrounds, like she once had been, the kind of young people who might too come to see themselves as Atlantican emissaries.

in your life?

in your life?